Zoltan Shtern

Uzhgorod

Ukraine

Interviewer: Ella Levitskaya

Date of interview: April 2003

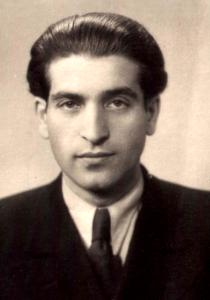

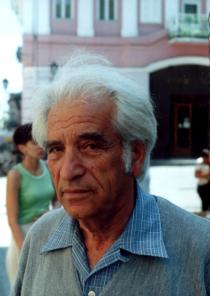

Zoltan Shtern is a man of average height, slim and lively. He has thick gray hair and very young eyes. We met in Hesed in Uzhgorod. Zoltan still works as a lawyer regardless of his age. He has a busy schedule and could hardly find time for this interview. Hesed is near his office in the town collegium of lawyers and we decided to meet there to save time. He speaks slowly as if weighing each word. It must be his professional trait. Perhaps, the story that he told me about the years that he spent in the Gulag 1 camps may seem incomplete, but it was difficult for him to recall this period of his life and he asked my permission to skip the details.

My paternal grandmother and grandfather were born and lived in the village of Rososh, in Svaliava district, Subcarpathia 2. This was a small village. There were about 30 families living there and about ten of them were Jewish. My grandfather, Nuchim Shtern, was born in the 1860s. I don't remember my grandmother's name. She was a few years younger than my grandfather. When I knew my grandfather he was retired. I think he earned his living as a coach driver. My grandmother was a housewife. They were poor. I only saw them a few times and remember very little about them. I can't tell what my grandfather looked like. All I remember about my grandmother is that she was short and always wore a kerchief on her head. They had four or five children. I didn't know any of them. My father, Moshe Shtern, was born in the 1890s. He never told me about his childhood or youth.

My father's parents were religious. There was no synagogue in Rososh and my grandfather went to the prayer house in the neighboring village of Holubino on Sabbath and Jewish holidays. There were only men praying there. Women prayed at home. My father's parents celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and followed the kashrut. I can't remember any details. They spoke Yiddish and Hungarian in the family.

My grandmother died in 1939. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Lubino near Rososh. It was a Jewish funeral. They also buried the dead from the villages of Pasika and Holubino which had no Jewish cemeteries there. Grandfather Nuchim died one year later, in 1940. He was buried near my grandmother. Lubino no longer exists and my grandparents' graves are gone. There are floods in Subcarpathia. They wash away villages and that's what happened to Lubino. The residents of the village moved to other places. The same happened to Rososh.

I know a lot more about my mother's parents. They lived in the village of Pasika in Svaliava district. My grandfather, Kaske Aisdorfer, was born in Pasika in the 1850s. I don't know where my grandmother, Rosa Aisdorfer, came from. She was born in the 1860s. Her Jewish name was Reizl. I don't know her maiden name. Some of my grandfather's relatives lived in Pasika, but I can't remember any of them.

Grandfather Kaske was a short stout man. He had a big black beard with streaks of gray hair. My grandfather wore a kippah at home and a hat to go out. He didn't have payes. Only Hasidim 3 wore payes in Subcarpathian villages. My grandmother was a short slim woman. She wore plain clothes like all other women in villages. She always wore a dark kerchief on her head.

My grandfather owned a water mill. The villagers paid him with money or flour for grinding the grain. My grandparents were quite wealthy. My grandmother was a housewife after she got married.

My mother, Mira Aisdorfer, was born in the 1890s. I don't know all of my mother's brothers and sisters. There were six or seven of them. My mother's older brother whose name I don't remember moved to Galanta, a big resort town in Czechoslovakia, in the early 1920s. He went to work in a restaurant there and got married. Another brother, Kalman, was two or three years older than my mother. He lived in Pasika. The Hungarian fascists shot him in 1942. I don't know any details. Her younger brother, Iosif, went to work in the village of Vary near the Hungarian border in the early 1930s. Some people there took illegal emigrants to Israel. In 1933 Iosif was taken to Israel via the Netherlands. He lived his life there and died in 1985. When I traveled to the USA in the 1990s I tried to find his family in Israel from there, but I failed. I also knew two of my mother's sisters. I don't know whether they were older or younger than her. One of them, Sima, lived in Pasika with her husband. They had two children, a son and a daughter. The fascists killed their son. Their daughter, Rukhl, is in the USA. I met with her and her children when I traveled there. My mother's other sister, Rivka, got married and moved to her husband, who lived in a village in Svaliava district near the border with Hungary. They all perished during World War II.

My mother's parents were religious. Pasika was a small village, but it was still bigger than Rososh. There were about 60 families living there and about 15 of them were Jewish. The Jews were craftsmen for the most part: tailors, shoemakers, blacksmiths and saddle makers. There were also tradesmen among them. There was no synagogue in Pasika, but there was a prayer house. Women were allowed to come to the prayer house four times a year: at Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur and Purim. The men went there on Sabbath and on Jewish holidays. On weekdays my grandfather prayed at home in the morning and in the evening. They raised their children religiously. My mother could read and write in Yiddish and Hebrew and knew the prayers. I don't know where she got her religious education. The boys studied in cheder and the girls usually studied with a visiting private teacher. The family celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays at home and followed the kashrut. They spoke Yiddish and Hungarian at home.

My parents got married through matchmakers. It was customary with Jews at that time. Of course, they had a traditional Jewish wedding. It couldn't have been otherwise at that time. In smaller towns Jews observed all traditions. They lived in close communities and everybody watched everyone else and people were concerned about rumors or their neighbors' opinions.

After the wedding my parents settled down in a house that my father bought in Pasika. This was an adobe house. Sun-dried bricks were a common construction material in Pasika. Only wealthier people could afford wooden or stone houses. There were two rooms in the house. The bigger room housed my father's shop and the other room served as living quarters. There was also a kitchen with a big Russian stove 4 for cooking and heating.

My father had a small store. Every now and then my mother or my older siblings helped him there. The assortment of goods included kerosene, salt, flour and bread. My father brought bread from a bakery. He earned very little and they could hardly make ends meet. My mother had twelve children. Five died in infancy. All of us had Hungarian names written in our official documents and a rabbi issued a birth certificate with a Jewish name. All sons had their brit milah in accordance with Jewish traditions. My oldest brother, Vili, was born in 1914. His Jewish name was Josl. Then came my older sister Jolana, born in 1917. Jolana's Jewish name was Hana. I was born on 1st September 1919. My Jewish name is Esotskhar. Then came my younger brother Miki, Mekhl in the Jewish manner, born in 1921. My other two brothers, Yankel and Herman, and my other sister, Sima, were much younger than Miki: they were born in 1928 and in the 1930s, accordingly.

There was very little land near the house where we had a wood-shed and a stable in which we kept our livestock. There was no garden or kitchen garden near the house. My grandfather Kaske, my mother's father, gave us a plot of land of about 1,500 square meters where we grew potatoes for the family. We were a big family and mother was always concerned about food provisions. At first my mother kept a goat of a breed from Czechoslovakia. This goat gave more milk and it was delicious. Then we had a cow that we kept in the stable in the yard. There were also chicken and geese there. One had to keep livestock to make a living.

My father was a thin man of average height. He didn't have a beard or payes. He wore a black yarmulka called 'shrama' in local dialect. My mother wore a wig after she became a married woman. Sometimes she wore a kerchief.

My parents were religious. My father had a tallit and tefillin. He went to the prayer house on Sabbath and Jewish holidays and prayed at home on weekdays. We celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays. My parents weren't fanatically religious, but they strictly observed Jewish traditions. We knew that the situation was radically different in Russia and Ukraine after the Revolution of 1917 5: that religion had no big place in life and that Jews didn't have an opportunity to lead the life they wanted in this respect. During the Austro-Hungarian and Czech rule, the Jews observed their traditions.

The Jews in Subcarpathia didn't know any oppression during the period of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy before 1918 or afterwards when Subcarpathia became a part of Czechoslovakia. During Czech rule Jews even enjoyed more rights than before. They could hold official posts and even own big enterprises. Religiosity was appreciated. There was democracy in Czechoslovakia. President Benes 6 respected and supported the Jews. There was rabbi Chaim Shapira 7 in Mukachevo. President Benes awarded him the title of doctor of sciences.

We only spoke Yiddish at home. In Pasika all Jews spoke their mother tongue, Yiddish. In towns, like in Mukachevo, many Jews spoke Hungarian even when this area belonged to Czechoslovakia and children learned this language from their parents who were used to speak it. I believed that Jews had to speak their own tongue. We also spoke fluent Czech.

There was no shochet in our village. He came to work in our village from Holubino once a week. All Jews always waited for him to come to the village: they didn't eat any meat unless it came from the shochet. Nobody slaughtered any poultry, but the shochet. Then my mother kept the meat in water for six hours to make it kosher.

We celebrated Sabbath. Our mother cooked food for two days. It wasn't allowed to even warm up food on Saturday and she left pots with cholent in the oven of our Russian stove to keep it warm until the next day. We always had gefilte fish and challah on Sabbath. The family always got together on Friday. My mother lit the candles and said a prayer over them. Then we all said a prayer and my father blessed the food and we all sat down for dinner. My father didn't work on Saturday. He went to the prayer house and when he came back home he read the weekly portion of the Torah to us and told us stories about the history of the Jews.

We started preparations for Pesach long before the holiday. One Jewish family in Pasika made matzah for all the Jewish families. The other families gave this family orders in advance and they knew the quantities they had to make. My mother also stored one to two hundred eggs for Pesach. Many eggs were used throughout the eight days of the holiday: they were used for cooking and baking pudding or cookies. The chickens and geese were taken to a shochet. My mother melted goose fat to do all cooking on Pesach. She made geese stew and boiled chicken. Every day we had chicken broth with matzah and boiled chicken for lunch. We didn't eat any bread. My mother also baked strudels with jam and nuts and cookies. On the eve of Pesach we took the fancy crockery from the attic where it was kept in a box. My father conducted the first and the second seder. My older brother and I knew Hebrew and we posed the traditional questions [the mah nishtanah] to him. The adults were to drink four glasses of wine at seder. There was one extra glass for Elijah the Prophet 8. The door was left open during the seder for him to enter the house.

On Rosh Hashanah everyone went to the prayer house. My mother made a festive meal and always put a saucer with honey and slices of apples on the table. We dipped the apple slices into honey and ate them to have a sweet and happy year to come. On Yom Kippur the adults fasted for 24 hours. [Editor's note: According to tradition, Jews have to fast 25 hours on Yom Kippur.] Small children fasted after coming of age, boys at the age of thirteen and girls at the age of twelve. At Chanukkah mother lit one candle more each day. The shammash was lit on the first day of Chanukkah to keep burning throughout the holiday. All guests gave children some money. As for Purim and Sukkot, I don't remember how they were celebrated.

At the age of six I went to cheder in Svaliava, seven kilometers from Pasika. There was no cheder in Pasika, but my parents wanted me to have a Jewish education. My older brother Vili also studied in this cheder. I commuted to Svaliava by train. A monthly ticket cost me 10 Czechoslovak crowns. My parents gave me money to buy a ticket, but sometimes I spent this money to buy sweets. I then commuted by train for free and I only paid for a ticket when the conductors caught me. I left home in the morning and came back in the afternoon.

At the age of seven I went to a Czech elementary school in Pasika. I attended classes in the morning and in the afternoon I went to Svaliava where I had private classes with a rabbi. I studied Hebrew and learned to read and write in Hebrew and Yiddish and also studied the Torah and the Talmud. There were several Jewish children in the Czech school. The attitude toward us was very friendly. I studied well. There was a state school in Svaliava where children could finish the 5th-8th grades. Those that planned to enter the Commercial Academy in Mukachevo had to finish another year at school. My parents rented a room for me at a Jewish family's place in Svaliava. My landlady cooked for me and did my laundry. I spent my weekends at home. Besides going to secondary school I had classes with a rabbi until I had my bar mitzvah.

I had my bar mitzvah in the synagogue in Svaliava when I turned 13. I prepared a small speech, a droshe. I had to recite a section from the Torah and comment on it. My parents and relatives were at the ceremony. My parents brought vodka and snacks for the attendees. I can't remember what my droshe was about, but there was something else that made my bar mitzvah quite memorable. There was some vodka left and my parents told me to take it home. I did carry it home, but well, some was gone on the way... Since that time I've hardly ever drunk alcohol.

In 1930 there was a fire. There was a factory near our house. The fire started there and then spread onto our house. The fire was put out promptly and didn't cause much damage. However, a flood in 1932 destroyed our house. The village council decided to elevate the level of the street and spread about half a meter layer of soil. Then our houses turned out to be half a meter below the surface. In spring the river flooded the streets and houses. Our house was washed down within two hours. We moved to my mother's father. Those villagers that suffered from the flood sued the government and the government accepted the lawsuit. We received compensation, but it wasn't enough to build a new house. There had to be high foundations to protect the house from floods.

My parents had to take out a loan from the bank. In 1934 they completed the construction of a big brick house on the spot of our old house. There was sufficient room for a shop in the new house. However, my parents failed to pay back their debts to the bank. The bank ordered us to move out and put our house on sale in 1936. We didn't have a place to live and local communists insisted that the bank allowed us lodging at least on the verandah. There was a Communist Party during the Czech rule. The communists helped us to take our belongings onto the verandah. I cannot say how they managed to obtain permission for us to lodge in the house that belonged to us, but the outcome was that we lived on the verandah for almost two months. My parents informed my mother's brother Iosif, who lived in Israel, about what had happened to us. [Editor's note: Israel came into existence in 1948; Iosif must have lived in Palestine under British mandate.] Iosif came from Israel and bought out our house from the bank for a much lower amount than my parents invested into its construction. We moved back into our house.

I finished nine years in Svaliava and in September 1936 I entered the Commercial Academy in Mukachevo. The building of this academy is still there. It provided very good education and its graduates had no employment problems. It wasn't easy to enter this academy. Within the current educational system this academy would be equal to college. It prepared high- skilled specialists. Professors that left Russia after the Revolution of 1917 worked in the academy. Besides special subjects students studied foreign languages, shorthand and typing. I was an excellent student throughout all years of my studies and always helped other students that weren't doing so well. There were Jews, Czechs, Hungarians and Ukrainians in our group. There were no negative attitudes towards Jews. There was no anti-Semitism at that time. My brother Vili had also finished this academy and went to work as an economist at a factory.

In 1938 Hungary occupied Subcarpathia. Mukachevo was occupied in October 1938. I was a student of the Academy then. Hungary was an ally of fascist Germany. On 15th March 1939 Hungary occupied Svaliava district. I returned home before I finished my 4th and last year. There was an affiliate of the academy operating in Svaliava and I decided to finish my studies there. The Germans already held many official posts. When I continued my studies we had to greet our lecturer with 'Heil Hitler!'. It was an order that the representative of the Germans in the administration of the academy issued. After finishing my studies I became an economist and accountant.

After Subcarpathia was occupied Hungary began to implement anti-Jewish laws [anti-Jewish laws in Hungary] 9 and oppress Jews in every possible way. Jews had no right to own stores or enterprises; anything that might have brought any profit to its owner. A Jewish owner could either sell or transfer his property to a non-Jewish owner. Otherwise the property was taken into state ownership and the government used it at its discretion. My father had to transfer his store to a Ukrainian owner. My father began to work for him. He did everything he used to do when the store belonged to him, but now he received a miserable salary for his work.

Men that were fit for the army service were obliged to register at the gendarmerie once a week. Every week I walked six kilometers from Svaliava to register at the commandant's office. At times the gendarmes tortured and beat me. In August 1940 I decided to escape and cross the border. I didn't have much choice. Germany occupied Poland in September 1939. Polish refugees going via our village told us about fascism and the way the fascists treated the Jews. They were all heading for the USSR that seemed a rescue from fascism to them. Czechoslovakia was occupied by the fascists and there was only the USSR left. [Editor's note: Czechoslovakia was split, the Czech part was occupied by Germany and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was created, while Slovakia became a German satellite.]

We heard about life in the USSR after the Revolution of 1917. Unfortunately, we only had access to the official propaganda: radio and newspapers. I imagined the USSR to be a country of equal possibilities, freedom and justice. I also remembered how the communists had helped us when the bank chased us away from our house. If I had known the truth about the USSR or what they did to refugees who were trying to escape from the fascists - I wouldn't have gone there. Well, I went through this. I've lived through four disasters in my life: fire, flood, Stalin's camps and life in the USSR.

I couldn't tell my parents that I was crossing the border. My mother seemed to have an inkling that something was going to happen: she kept crying telling me, 'stay...'. I reached an agreement with a guide who took refugees across the border. We were to get together in a village, 30-40 kilometers from Pasika. I don't remember its name. On 20th August 1940 I left home without even saying goodbye to my parents. I still feel sorry about it, but at that time I was planning to take my parents to the USSR as soon as I settled down there. Three other people from my village joined me. There were three from Svaliava and others whom I don't remember. There were 54 of us in total. The majority were young people and there were older people, too, with their wives and children. Almost all of us were Jews, but there were a few Ukrainians as well.

On the night of 21st August we got to the border with the USSR. The guide took us to the border, showed us the way and returned home. We crossed the border, took a nap and decided that we had to look for a frontier guard. That was where the story started and it was a big story. The frontier guards found us before we found them. We were glad at first, but then our joy ebbed away when they ordered us, 'Stand up, line up, a step to the left, a step to the right shall be considered as an effort to escape and then we shall apply our weapons'. I will never forget these words. My other life began on 21st August 1940.

We were taken to a camp in Skole, Lvov region [120 km to Lvov]. There were 1,500-2,000 inmates in the camp. We weren't told what we were charged with and we sincerely didn't understand why we had been arrested. The camp was in horse stables. We slept on three-tier plank beds. We were provided one meal per day. We ate with wooden spoons from wooden plates. After three months we were taken to prison in the town of Striy, Lvov region [75 km from Lvov] by train. There were about 300 of us in the train and there were many guards. We stayed several months in prison in Striy. Groups of prisoners arrived every day. Most of the prisoners were people that had crossed the border. There were people from Subcarpathia, Polish and Ukrainian residents.

In winter 1941 we were taken by freight train to a big camp in Starobel'sk. The trip lasted seven days. We were given one meal per day. We were given salty herring, but no water. There were a few thousand inmates in the camp. The camp was in a former monastery where barracks had been constructed. There were people from Subcarpathia, Poles and Ukrainians. We stayed there for a few months. I don't remember how many. There were numerous guards in the camp. We didn't work in this camp. We were allowed to stay in a barrack or walk in the camp. We were given prisoner clothing.

On 11th June 1941 we boarded a freight train again to travel to Vladivostok [about 2,000 km in the Far East]. We arrived at Nakhodka bay near Vladivostok. When the train stopped in Irkutsk we overheard through our barred windows that Germany had attacked the USSR. [This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War.] 10 This was on 22nd or 23rd June. From Vladivostok we were taken to Nakhodka by trucks with tarpaulin tents. We stayed there several days and from there we were taken on a barge called 'Jurma' to Nogaev bay in Kolyma. Again, there were numerous guards. We sailed nine days. Many of us were seasick. It was such pain. It was cold and we only wore prisoner robes.

In Nogaev bay we were lined and marched to the distribution point in Magadan from where prisoners were distributed among Gulag camps. We stayed in the distribution camp for about two weeks. I was in a group of about 400 prisoners sent to Moliak camp. From there we were sent to Obiedinenniy camp on trucks. This was in winter 1941-42. Barracks in Obiedinenniy mine were in the process of construction and some of them didn't even have a roof. There were two and three-tier plank beds and gasoline stoves. In a barrack for a hundred inmates there were two gasoline stoves on the opposite ends of the barrack. We took turns to warm up near the stoves. Every prisoner could get close to the stove two to three times a night. Most of the prisoners died from hunger and cold in Obiedinenniy mine. We didn't go to work there.

In early 1942 the president of Czechoslovakia, Masaryk 11, the follower of Benes, signed an agreement for assistance and support with the USSR. Those residents of Subcarpathia that were born during the Czech rule were Czechoslovak citizens and Masaryk asked to review their cases. [Editor's note: Masaryk resigned from his office in 1935 and was succeeded by Eduard Benes. As the head of the Czechoslovak Provisional Government in London it could only have been Benes who signed such an agreement with the Soviets.] Then we were transported to Moliak camp. This camp had heating and we got food that wasn't too bad. We recovered within three months and then the camp management decided that we were fit to go to work. Moliak was a gold mine. There were open developments of gold and there were underground mines. There were rich gold veins and nuggets of gold. Once I found a nugget. There was a bonus given for it, but where could we spend the money if there were no stores in the camp? We weren't allowed to leave the camp and there was nothing we could do...

In summer 1942 I was summoned to the director of the gold mine. He announced that I was sentenced to three years in a high security camp for illegal crossing of the border. The director had just received our documents, but actually, it was my third year in imprisonment. This was not the worst sentence under article 80 of the Criminal Code of the USSR. When a person was accused of espionage the sentence was over five years. If a person had relatives abroad the sentence was over eight years of imprisonment. I was sentenced to three years for illegal crossing of the border. How this verdict was reached when there were no interrogations or investigations - who knows.

In late 1942 I was sent to Burkhala mine. There were several mines: Northern, Western, Susuman, Yagodny; I'm beginning to forget their names. We were sent to different mines and did similar work to what we had done in Moliak. In 1943 many former citizens of Czechoslovakia were summoned to the distribution camp in Magadan from where we started on our way to Kolyma. I was the only Jew among them. All Czechoslovak citizens were released and sent to a Czech legion formed in Buzuluk under the agreement between Stalin and Masaryk. However, when they read the list of this group my name wasn't on it and I stayed in the distribution camp, and after two or three weeks I was sent back to Burkhala without an explanation. I continuously requested appointments with the director of the camp asking for an explanation. I had been sentenced to three-year imprisonment. It had expired a while before and nobody had extended my sentence. I kept writing letters to all Soviet and party leaders: Stalin, Beriya 12, Kaganovich 13, Molotov 14; all of them. There was no response. I worked at Burkhala from 1943 to 1947. We weren't paid for our work, of course, we didn't get any food, no medical care, the conditions were terrible: there were barracks for 100-200 prisoners, hardly any heating, severely cold climate. Summer only lasted a few weeks and there were frost up to minus 40 degrees for the rest of the year.

Throughout this time I had no information about my relatives. The camp inmates weren't allowed to correspond with their families. It happened only once that I bumped into some short report in a piece of newspaper I got incidentally, saying that the Soviet troops had crossed Pasika liberating Subcarpathia. At least I knew that my village was still there.

On 30th January 1947 the director of the camp called me. He looked confused and said that he had already had problems since my sentence had been over for a long time and I was still kept in the camp. I was sent to the human resource department of the mine to obtain documents. I didn't quite know the way. They just explained to me that I had to cross a pass in the mountains and turn a few times before I came to the village. It was a miracle that's hard to describe: for the first time in many years I had no armed escort - I was free! I don't think I felt cold.

In the human resource department I obtained the certificate of release from the camp and a job assignment to work in Burkhala mine as an employee. The date of release in my document is 30th January 1947. I returned to the office of the chief engineer in Burkhala. He asked me where I wanted to work and I answered that I wanted to return home. He explained to me that I only had the right to live in Kolyma. I knew several Jews that were shoemakers and tailors in Magadan. To leave Kolyma I needed a permit without which I couldn't even get a train ticket. Besides, I didn't have money. I worked as a laborer in the stables for two weeks. Then I was summoned to the office again.

They reviewed my documents that said that I had finished the Commercial Academy in Mukachevo. I was sent to work as a worker in a store at the mine and they promised to make me a shop assistant in a short while. There were four shop assistants in that store. This was a store for residents and employees selling meat, sausage, butter and sugar per food coupons. I had been a worker there for two months when the director of the store was transferred to a store in Yagodny mine and I took his place. I lived in a hostel near the store. When I became director I received a room of my own in this hostel. I received a salary and had sufficient food. The people and management of the mine treated me well. Throughout this period I kept writing letters to Moscow. I was writing these letters and I never got any response. I didn't even know whether my letters ever left Kolyma.

In December 1947 I was summoned to the office of the mine. They told me that I was allowed to leave Kolyma. However, it was next to impossible to leave Kolyma in winter. The rivers were frozen and the planes were only for the management to fly on business. A few days later the manager of the mine and his family were going on vacation and he offered me help. I was so happy to get this offer: I could go to Magadan in a bus. This was in February 1948. The temperature was minus 50 and there was heating in the bus. I obtained an official certificate saying, 'Released from the camp and is allowed to go to the continent' [the European part of the USSR].

I was sent to the town of Voronovitsa in Vinnitsa region [20 km to Vinnitsa, 215 km to Kiev]. From Magadan I flew to Novosibirsk via Yakutsk. It was faster to go via Khabarovsk, but I would have had to wait for a whole day for the plane via Khabarovsk and I was too impatient to be on my way. From Novosibirsk I took a train to Moscow. I wasn't allowed to live in big towns, but it was all right to travel through them. I stayed in Moscow a day and took a train to Vinnitsa. In Vinnitsa I rented a room from a poor Jewish family. A few days later our district militiaman came to tell me that my point of destination was Voronovitsa. I have no idea how he knew about where I was to go, but you know, that was how information spread in the USSR. I went to Voronovitsa where I rented a room from an old woman. I had to go to work, but all I could think about was going home.

I called the village council in Pasika and asked them to find someone from the Shtern family. I told them when I would call back. When I called again Bela Shtern was on the phone. He wasn't a relative, just had the same surname as I. I talked to him. He said that none of my relatives were in Pasika, but he didn't offer any details. He promised to send me money to travel home and said that he would tell me what I wanted to know when I came there. I kept writing to Kiev trying to obtain permission to travel home since Subcarpathia belonged to the Ukraine already. I also requested an appointment with the chairman of the regional executive committee in Vinnitsa and the KGB 15 office, but there was no response.

Throughout the few months of my life in Voronovitsa I had meals in a diner. It was inexpensive and I had to be saving for my return home. I was lonely and wished I could talk to someone. I met a young waitress there. I told her that I wanted to go home, and was waiting for permission and money to buy a ticket. Later this woman turned out to be a KGB informer. Once a KGB officer came to the diner where I used to have meals. He checked my documents and took me to the district militia office. I was kept there for several hours. They checked my documents, apologized and let me go. For the rest of my life they watched me and kept me under control. Shortly afterward I received permission to go home. In October 1948 I left for Subcarpathia. I left Kolyma in February and only in October, eight months later, did I manage to reach home.

Shtern sent me money and I bought a ticket to Lvov. I didn't have one kopeck left. In Lvov acquaintances from Subcarpathia helped me to buy a ticket to Uzhgorod. Upon arrival I had to register at the KGB office. They were aware of my arrival and waited for me. From Uzhgorod I got a truck ride to Pasika. I didn't have a penny left. The villagers were happy to see me. They helped me to get to Bela Shtern, who had moved to Svaliava. He treated me like one of his family. He told me that in 1944 the Hungarians summoned young men to forced labor at the front and the remaining Jews - women, children and old people - from Subcarpathia were sent to concentration camps. Only a few survived. My parents, my older sister Jolana and my younger siblings Yankel, Herman and Sima perished in Auschwitz in February 1945. I thought that my brothers Vili and Miki also perished. A few years later I got to know that they had survived. They were liberated by the Americans and knowing that Subcarpathia became Soviet they decided to move to the USA. Shtern also told me that my mother's parents died in 1942, but I don't know where they were buried.

I lived with Shtern and he treated me like his family. He shared his food and helped me to get me clothes. I lived like this for a month. I had to start looking for a job. I met my childhood friend, my fellow student from the academy in Mukachevo. I used to help him with his studies when we were students. He became the prosecutor of Mukachevo. He asked me where I wanted to work and I said that I would agree to any work I could get. My friend had a good relationship with general Andrashko, the prosecutor of Uzhgorod region, and knew that the prosecution office needed a logistics supervisor. My friend phoned Andrashko and asked him to employ his friend Zoltan Shtern.

I went to the prosecution office in Uzhgorod. The general asked what I wanted to do and I said I wanted to be logistics supervisor. Andrashko considered my response and then said 'No, you shall not work as logistics supervisor'. I thought it had something to do with my sentence in the camp, and was about to leave, when he continued, 'You shall not be logistics supervisor, you shall be investigation officer'. I began to refuse: firstly, I was a convict, and my sentence hadn't been canceled, secondly, I was no lawyer. The general said he didn't believe my sentence and made me investigation officer in the prosecutor's office of Irshava district.

My colleagues were very nice and friendly. They helped me to get into the essence of this job. It took me a couple of months to learn everything about this job. From Irshava prosecutor's office I was transferred to the prosecutor's office of Uzhgorod district. I entered the extramural department of the Faculty of Law of Lvov University. The regional prosecutor signed a request to admit me to university and I became a student without any problems. I took a holiday to go to Lvov to pass my exams. I was an excellent student and my lecturers treated me well. I never faced any anti-Semitism in Subcarpathia. Anti-Semitism developed only when the new arrivals from the USSR began to prevail. These people became the source of manifestations of anti-Semitism, as far as I'm aware of it.

In 1952 the Ukrainian prosecution office got to know that I had brothers in the USA. It was dangerous to have relatives abroad 16, particularly, if it was a capitalist country, even though we had no contacts. One could be fired or even be subject to more severe punishment. The General Prosecution Office issued the order of my dismissal. This is what was written in my employment record book: 'Fired per order of the general prosecutor of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic'. Even though I was shocked at the loss of my job I was happy to get to know that my brother Vili and Miki were alive. The KGB officers informed me about it. Of course, they spilled no details and I couldn't correspond with them, especially because I was a former convict.

By that time I had finished three years at the Faculty of Law. I decided to take advantage of this sudden unemployment factor and switched to the daytime schedule of studies. I got accommodation in a hostel in Lvov and attended classes every day. I was the oldest student in my group and my fellow students treated me with respect. When I worked in the prosecutor's office my management offered me to join the Communist Party. They said it was good for my career. I became a candidate to the Party then and in 1953 I was admitted to the Party when I studied at university. There was a party meeting in the concert hall of the university when I was to be admitted to the Party. There were about 600 professors and students present. I briefly told my story. There was silence in the hall when I finished. Then people started coming to shake my hand or give me a pat on the shoulder. Of course, I mentioned that I was a Jew. I never concealed my Jewish identity. I wrote in all forms that I was a Jew. If I did otherwise it would be humiliating myself.

Frankly speaking, there is a lot of good in the idea of communism. What Stalin and his followers did to it is a different story. I felt it myself. Until I got to the Soviet Union I didn't know what was going on here. 1,500 or 1,600 camp inmates had been killed before I arrived at Moliak. So many people perished. And this was just one of many camps where all the inmates were exterminated in one day. I tied this to the name of Stalin, but at the same time I couldn't believe that the leader of such a huge country could be so cruel. Whatever there was to it, it's true that during World War II people fought in the name of Stalin. Millions believed him unconditionally. Of course, people were aware of some things, ignorant about many others or closed their eyes on some.

I remember well the Doctors' Plot 17 in January 1953. Many Jewish students were expelled and professors were fired from Lvov University. I was left in peace. I didn't know why, but I stayed. Later, when I talked with friends that were doctors in Mukachevo, they told me that many weren't just fired, but also sent to camps. They were released after Stalin's death in 1953.

Stalin's death on 5th March 1953 wasn't a big loss for me like it was for the majority of the Soviet people. I was an outsider, different from those who grew up during the Soviet regime. Besides, people that went through the camps were disillusioned. I understood that Stalin had to know what was happening in the country and nothing could happen without his blessing. I felt this and Khrushchev's 18 speech at the Twentieth Party Congress 19 confirmed my conviction about the criminality of the Stalin rule. After the cult of Stalin was denounced at the Twentieth Party Congress I was rehabilitated 20 in October 1962. The regional court of Lvov reviewed my case and determined that I was subject to oppression in fascist Hungary as a Jew and there was nothing criminal about my crossing the border to the USSR.

I graduated from university in 1954. My friends working in the Subcarpathian regional executive committee sent the university a request for issuing me a job assignment to work there. Upon graduation I received a job assignment to the Subcarpathian regional executive committee. I was employed as manager of the legal and protocol department of the executive committee. I worked there for three and a half years. I had very good relationships with my management and even got a raise from the Council of Ministers of Ukraine. My salary as a manager was 690 rubles and the Soviet of Ministers added 300 rubles for excellent performance. This was a lot of money: few people in the USSR earned this much. I had rented a room before, but the executive committee gave me a one-bedroom apartment.

In the house that we had owned before the war there was a two-year local school. The local administration allocated funds for the repair of this house and the school director appropriated this money and bought a house in a neighboring village. Then he suggested that I claimed my rights on our house. My parents had been the owners of this house. I had my inheritance documents for the house issued according to the rules. Since I didn't feel like disowning the children from their school building the secretary of the district party committee proposed that I sold the house to the school. They could only pay the cost of the insurance evaluation of the house which was half the price of the house. I agreed, but then they deducted the cost of the repairs supposedly completed. To avoid the inspection of the building which would for sure have proven that no repairs had been done whatsoever the school director made an agreement with a local journalist who wrote an article saying that I was taking away the building from the children. Of course, if there had been an investigation I would have been proven innocent, but nobody felt like clearing things.

The regional party committee decided to remove the source of conflict from the executive committee. And I was this source. They forced me to submit my letter of resignation since otherwise they would have fired me under a criminal code and they would have had no problem in plotting charges against me. My boss, the secretary of the executive committee, was reluctant to let me go, but he couldn't fight with the secretary of the regional party committee. I quit the executive committee and became secretary of the Trade Unions of Governmental Employees where I worked for several years. When I worked as investigation officer I met the chairman of the regional court, Martin, who later became chairman of the collegium of lawyers.

In 1965 he convinced me to start working as a lawyer. That was when I became an attorney and I've never regretted taking this decision. I'm happy doing this work. I can protect people. I was awarded the title of 'Honored Lawyer of Ukraine'. I was the only lawyer in Subcarpathia that was awarded this title. There's a militia colonel, my good friend, and prosecutors and judges with this title, but I'm the only attorney. This title allows me an increase of my salary of 85 hrivna [about USD 16] that I will be receiving from January 2004. It's important for me. I receive a 157 hrivna [about USD 30] pension like the majority of the pensioners in Ukraine. My capital are my friends, that is, that I have many and nice people that I meet a lot. Many people know me in Uzhgorod. They trust and respect me. I have Jewish, Ukrainian and Hungarian friends. I don't care about nationality. A decent personality is what matters. However, it happened so that most of my friends are Jews. Jews are my people. I've always thought about them and it hurts to witness demonstrations of anti-Semitism.

I've always been a Jew in my heart. I've had faith in God and always prayed at home in the morning. I couldn't observe Jewish traditions or celebrate Jewish holidays at home since I worked for the government and was a member of the Party. The state struggled against religion 21 and religious people were persecuted. If I had been seen at the synagogue I would have lost my job and party membership card. Considering my conviction it might have been even worse. I also celebrated Soviet holidays since it was necessary to do so.

In 1961 I married Prascovia Goncharenko, a Ukrainian girl. I met her at a party. Prascovia was a student of the Faculty of Philology of Uzhgorod University. My wife is much younger than I am. She was born in a village in Sumy Region in 1936. I've forgotten the name of this village. Her parents were kolkhoz 22 farmers. After finishing secondary school Prascovia entered Uzhgorod University. Her childhood dream was to become a teacher. We saw each other for about half a year and then we got married. We had a civil ceremony and in the evening we had a wedding party to which we invited our acquaintances. My wife took my surname after we got married.

Upon graduation from university she was an elementary school teacher. She loved children. Every now and then strangers approach me in the street telling me that my wife was their first teacher. I can tell you frankly that I appreciate it. In the 1970s the school management applied to the higher authorities requesting the approval of Prascovia's award of 'Honored Teacher of Ukraine'. That was when my Ukrainian wife faced anti-Semitism. The director of the regional department of public education didn't like her Jewish last name of Shtern. He didn't forward her documents to Kiev. I got to know about it several years later.

Our first son, Evgeni, was born in 1962 and Victor followed in 1964. I tried to teach my sons Jewish religion and Jewish traditions. Regretfully, they were far from conceiving them. My sons were pioneers and Komsomol 23 members and lived in accordance with the laws of the USSR. They didn't identify themselves as Jews and were just Soviet people. In those years we didn't observe any religious traditions at home. We didn't celebrate Soviet holidays either. We celebrated our birthdays and our children's. We invited friends, had parties, listened to music and talked. We spent vacations traveling to Subcarpathia or to the Crimea with the family.

Evgeni wanted to become a teacher like his mother. After finishing school he entered the Faculty of Mathematics of Uzhgorod University. Upon graduation he became a teacher at a secondary school. He's a very good teacher and children like him. Victor finished the Faculty of History of Uzhgorod University. But, unlike Evgeni, he wasn't attracted by the idea of being a schoolteacher. He worked at school for some time upon graduation and then entered the Faculty of Law of Uzhgorod University. Upon graduation he obtained his license and became an attorney. He works well and I'm not saying this just because I'm his father.

My sons are married. I have four grandchildren. Evgeni has a Jewish wife. They have two sons: Evgeni, born in 1984 and Alexandr, born in 1987. They both study in Israel under a Sokhnut 24 student exchange program. Evgeni has finished school and is a university student. The younger one is still at school. He goes in for sports. He is a candidate for a master of sports in fencing. My grandsons are very happy in Israel. They often write me and call me. They have great perspectives and I'm very happy for them. Evgeni and his wife are going to move to Israel. I'll be missing them, but I understand that their children are there and therefore, their future is in this country. They study Ivrit. My son has quite a good command of Ivrit. Well, all I can do is pray to God for peace in Israel. My younger son, Victor, has a Ukrainian wife and they also have two sons: Sergei, born in 1987 and Andrei, born in 1994. They go to school.

When many Jews were moving to Israel in the 1970s I helped and supported them, but I myself never considered this option. I was born and grew up on this land, I like Subcarpathia and cannot imagine living in a different country. It's not that easy to cut off everything that was your life and leave. However, everybody must make his own decisions.

In the late 1980s perestroika 25 began. At first I was skeptical about it: I didn't believe in positive changes and believed the totalitarian regime to be unshakable. Later I saw that life was changing. Perestroika gave us a freedom we weren't used to. We could correspond with our friends and relatives living abroad, travel and invite them here. Mass media and television started to say things that in the past people were afraid to even mention when they talked in a whisper: about the lawlessness and repression in the USSR. An avalanche of information about our miserable life in the USSR depriving us of human rights fell upon us. However, many people tried to ignore it: it destroyed their understanding of the USSR, the Communist Party and many other things. Of course, from a material point of view life became more difficult: the standard of living became lower and there was unemployment that didn't exist before. As for me, I believed it was vitally important that we gained freedom. Anti-Semitism mitigated during the perestroika. Religious people weren't persecuted any more.

I've found my brothers in the USA. They live in Long Island, New York. They were very happy to hear from me. They thought I had perished. I've visited them five times since then. They are married, have children and grandchildren. They are pensioners. My brothers are members of the Jewish community. My older brother Vili is very religious. His older daughter's husband, his son-in-law, is a rabbi. He lives in Israel and lectures at Jerusalem University. Vili's family observes all Jewish traditions; they follow the kashrut, celebrate Sabbath and Jewish holidays. On Sabbath the family goes to the synagogue. My younger brother Miki isn't so deeply religious, but he and his family also go to the synagogue. Recently my older brother had a surgery. I always look forward to my younger brother's calls to tell me about how my older brother feels. He is 89 years old, not young any more. I cannot afford to call them in America: it's too expensive.

There are a lot of good things about the USA. I used to think that rich people built their riches on a dishonest basis stealing and lying while millionaires in the USA do a lot of charity and help the poor. However, basically I think that people in America aren't so open and friendly. I think it's better here. My brothers were telling me to move to the USA, but I never considered this option. I like my work and I like the people here. They treat me with respect. I think I would miss this if I left.

Another happy event in this country is that Jewish life began to revive. The synagogue began to operate in Uzhgorod. There were mostly older people attending the synagogue in the past, but after Ukraine gained independence younger Jewish people began to go to the synagogue, too. It never happens now, like it did before sometimes, that there aren't enough men for a minyan at the synagogue. I'm a Jew, I've been a Jew and I will always be a Jew. Lately I've attended the synagogue on Sabbath and Jewish holidays. I pray at home every day. I ask God for my brothers' health, for the health of my family and peace in Israel and Ukraine.

Many things have changed lately. Hesed plays a big part in the social life of Jews here. It opened in Uzhgorod in 1999. Hesed takes care of all Jews: from infants to old people. It provides assistance to the old and needy and supports them when they need medical care. It's also important that Hesed also supports our spiritual life. There's a number of clubs and studios in Hesed where everyone can find something to his liking. Older people appreciate the opportunity to socialize. I still work and don't suffer from loneliness while old people that don't go to work are very sensitive about an opportunity to talk. They get together in Hesed, which offers them interesting lectures, literature and music parties. We also spend Jewish holidays in Hesed.

Glossary