Naomi Deich

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Elena Zaslavskaya

Date of interview: November 2002

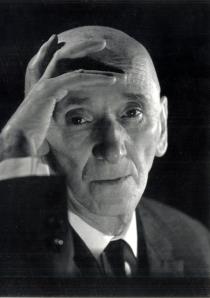

Naomi Deich is a tiny elderly woman. She is charming, easy-going and well- mannered. She speaks fluent Russian with no Jewish or Ukrainian accent. She has shrewd eyes. She keeps her house very clean. She has many books. An ancient grand piano occupies most of the living room. There are pictures and photographs on the walls. Everything shows that this lady is very intelligent and sensitive. The telephone rings all the time during the interview. Her friends and former students call her to talk.

My family background

Growing up

During the war

Post-war

Glossary

All I know about my great-grandfather on my father's side is that his name was Shmil-Nahmen Deich and that he owned a pharmacy. He died long before 1917 and was buried in the town of Radzivilov, somewhere near the border with Poland.

My grandfather, Shloime Deich, was born in Radzivilov in 1865. There were over 4,000 Jewish people in this town at the end of the 19th century. There were several Jewish schools, yeshivot and synagogues. There were also Polish and Ukrainian inhabitants. They had a good neighborly life and supported each other. In 1914, when World War I began, the Russian tsarist authorities accused the Jews residing near the border with Poland of cooperating with the Germans, and many Jewish families had to leave their homes.

My grandfather's family moved to Cherkassy. My grandfather owned a pharmacy in Cherkassy, but he didn't pay much attention to business and the family wasn't very wealthy. He wasn't religious, but he kept Jewish traditions under my grandmother's pressure. He was very fond of playing chess and reading non-religious books in Russian and Yiddish.

My grandmother on my father's side, Rivka Deich, nee Miserova, was born at the end of 1866. She was a housewife. I don't know where my grandmother was educated, but she could read and write in Yiddish and knew Hebrew. She also spoke English. My grandmother corresponded with her sisters, Surchik and Milka, who lived in the US since the 1900s, in Yiddish for many years. Unfortunately, their letters got lost, so I don't know any more about them. My grandmother was very religious. She always prayed and celebrated Sabbath and all Jewish holidays.

My grandfather died of typhoid in 1918. The Bolsheviks expropriated the pharmacy, and the family had to move to Kiev to look for jobs. My grandmother stayed in Cherkassy until her only son, Aron, my father, got married and moved to Kiev. She followed him and lived with him and my mother.

My grandparents had six children: five daughters and a son. The children were not raised religiously. All girls received their education at home and were very intelligent, educated and well-read ladies.

My father's oldest sister, Polia Deich, was born in 1890. She, her husband, Israel, and their children, David and Fira, lived in Leningrad. During the war Polia, Israel and Fira were in evacuation in Tashkent. David stayed in Leningrad throughout the blockade 1 and worked as correspondent for one of the main newspapers in Leningrad. Polia and Israel died in evacuation. Fira returned to Leningrad. Fira and David died in Leningrad in the middle of the 1970s and were buried in the Jewish cemetery.

My father's second oldest sister, Maria Kertman [nee Deich], was born in 1892. She was called Mutia at home. Maria was a hat-maker and worked at home. Her husband, Efim Kertman, was religious. He prayed, went to the synagogue and celebrated Jewish holidays. After the Revolution of 1917 he couldn't get adjusted to the new regime. Besides, he was epileptic. He didn't work. His family lived on what Maria managed to earn. During the war Maria and Efim were in evacuation in Kazan. Maria died in the early 1950s.

Her older son, Semyon, graduated from some institute and was chief production engineer at a plant in Kiev. During the war he supervised the evacuation of the plant to Kazan. Her younger son, Leo, graduated from Kiev University before the war and got married. His wife, Sarah Frantsevna, a Jew, and he were lecturers at Kiev University. Leo taught history and his wife was a professor of Russian literature. In 1949 they were accused of being cosmopolitans 2 and fired. They moved to Perm. Leo defended his doctoral thesis and Sarah defended her candidate of science thesis. Leo died in 1989 and Sarah passed away in the early 1990s. They were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Perm. However, they weren't religious and didn't observe any Jewish traditions.

My father's third sister, Bronia Deich, was born in 1898. She worked as a clerk at a plant in Kiev. During the war she was in evacuation with her plant in Kazan. She was single. She died in the middle of the 1970s and was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

The next sister, Hana Grinberg [nee Deich], was born in 1900. She was the first of all the children to receive education. She finished the Froebel Institute 3 and got a diploma for work with handicapped children. Hana's husband perished at the front during the Battle for Moscow in 1942. During the war Hana and her children were in evacuation in Middle Asia, where they almost starved to death, and then moved to Kazan. She was a teacher and later the director of an orphanage for handicapped children in Kazan. Hana died in 1982 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev. Her daughters, Jemma and Regina, were single. Regina went to Ivanovo after the war and managed a theater. Jemma is a pensioner now and lives in Kiev.

My father's youngest sister, Nelly Deich, was born in 1904. She studied at the Pedagogical Institute in Leningrad. She married Moisey Paniakh, a Jewish man. Moisey was at the front during the Great Patriotic War 4. Nelly and her sons, Victor and Alexandr, were in evacuation in Kazan. Victor and Alexandr live in Saint Petersburg now. Nelly and Moisey died in the middle of the 1980s. They were buried in the Jewish cemetery in Leningrad.

My father, Aron Deich, was born in 1893. He studied at cheder and went to work as soon as he could because my grandfather wasn't doing very well in his pharmacy. My father had to help to support the family. He never told me where he worked. In the middle of the 1920s he passed the exams at one of the schools in Kiev to get a certificate for secondary education. He was a very intelligent man and spoke and wrote excellent Russian. Besides, my father was a very talented man. He had a good knowledge of music and was very kind and sensitive. He loved my mother dearly.

My mother Rivka Deich [nee Zlochevskaya] was born to the family of Liver Zlochevskiy and Brukha Zlochevskaya in Cherkassy in 1889. All I know about her parents is that they lived in Cherkassy before the Revolution of 1917. Cherkassy was a fairly big town in Kiev province; nowadays it's a regional center. Its population was about 300,000 at the end of the 19th century. Over 30,000 of them were Jews. The town also had Russian and Ukrainian inhabitants. The Jews were craftsmen and merchants. There were several synagogues, yeshivot, trade schools and stores in the Jewish neighborhoods of the town. There were no conflicts between the people of different nationalities. My mother's father was a timber merchant. In the early 1920s the family moved to Rostov in Russia, escaping from the numerous pogroms 5. They had a distant relative in Rostov.

I only saw my mother's parents once in my life when my mother and I went to visit them in Rostov in 1928. They lived in a big well-furnished house. They were a wealthy family. My grandfather made a very pleasant impression. He wore plain clean clothes. He didn't wear a hat. My mother told me that my grandfather was moderately religious. He went to the synagogue on holidays and celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays.

I also remember a funny incident. My grandfather drank a shot of vodka at dinner. I saw how much he enjoyed it and asked for one for myself. My mother just looked at me astonished, but my grandfather dipped a piece of bread into vodka and gave it to me. I tried it, but spit it out immediately. I thought that nothing in the world tasted worse than vodka. My grandfather burst out laughing.

My grandmother seemed taciturn and hardworking to me. She wore clean clothes; that's all I remember. My mother's parents perished in Rostov when the Germans occupied the town in 1941. They ordered all Jewish people to come to the Mievskaya Balka at the outskirts of the town. [Mievskaya Balka is the mass gravesite of Jews killed in the Nazi invasion of the town.] They exterminated all Jews of the town within a few days by shooting them and throwing the dead bodies into a ravine.

My grandparents had seven children. They received secular education and weren't religious. My mother's older sister, Babl Mezhyborskaya [nee Zlochevskaya], was born in the late 1890s. She studied at the Russian grammar school in Cherkassy. She spoke Yiddish and Russian. She was a housewife. She was shot by the Germans in Rostov along with her daughter Ida and her 4-year-old son.

My mother's next sister, Rosa Palchitskaya [nee Zlochevskaya], was born in the middle of the 1890s. She studied at the Russian grammar school in Cherkassy. She moved to Rostov with her parents in the middle of the 1920s and studied at the Pedagogical Institute. During the war she was in evacuation with her family in Perm. Her husband, Abraham Palchitskiy, was a teacher of Hebrew. After 1948, when Jews were persecuted [in the campaign against 'cosmopolitans'], he couldn't find a job and dedicated himself to his son Milia and daughter Judith. Rosa worked as a linguist in Perm. She died in Perm in the 1950s and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. Her husband moved to the town of Kizil in the Ural, where his daughter got a job assignment after graduating from the Medical Institute. He died in Kizil in the 1970s. His son, a doctor, died in Perm in the 1950s and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. His daughter Judith is a pensioner and lives in Perm.

My mother's next sister, Polia Sinitskaya [nee Zlochevskaya], was born in the 1890s. I don't know where she studied, but she was educated. She never worked because she was confined to bed with polyarthritis. Her husband died of cancer in a hospital in Kiev in the late 1930s. Polia had two sons: Boris and Yuzia. Boris, the younger one, did all the housework and cooking. Both sons were on the front during the Great Patriotic War. Polia realized that she had to leave Cherkassy. She somehow got to Perm where her sister Rosa and our whole family were in evacuation. In 1944 she returned to Cherkassy. Her sons returned from the front, got married and stayed in Cherkassy. Polia died in the middle of the 1950s and was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

My mother's brother, Jacob Zlochevskiy, was born in the 1900s. He finished a Jewish grammar school in Cherkassy and graduated from some institute. He was an engineer. He perished at the Leningrad front in 1943.

My mother's other siblings, Ukkah Zlochevskaya and Grisha Zlochevskiy, were born at the beginning of the 1900s. After the Revolution of 1917 they became fond of revolutionary ideas and the equality and brotherhood of all people. They were involved in the Civil War [1918-1921] and perished at the beginning of the 1920s.

My mother finished a Russian grammar school in Cherkassy. She worked as a cashier in a small factory in Cherkassy. She didn't get married for a long time until her parents found her a fiancé in 1922 when she was 32 years old. [Editor's note: According to the Jewish tradition young people need to be introduced to one another. Rules do not allow young women to talk with strangers.] He was a distant relative, who was very wealthy and lived in Cherkassy. He was much older than my mother. Everything was prepared for their wedding, even a room for the bride and bridegroom, in the house of the relative. My father was staying in the house of this relative for some reason and met my mother. They liked each other and got married in 1922. It was a scandalous event for the family, but my mother's parents were very happy that my mother had met her true love.

My parents had a religious wedding with a chuppah in the synagogue in Cherkassy. Almost immediately after their wedding they left for Kiev. They both preferred to live in a big city. They got accommodation in an apartment with a long history. This apartment belonged to the Rindfor sisters before 1917. People only knew their last name. These sisters ran a kindergarten for children from wealthy families. They were also very fond of music. There was a big hall of 50 square meters in this apartment, and the sisters arranged big parties for composers and musicians. A famous Ukrainian composer, Lysenko 6, had his operas performed at one of those parties. I don't know what happened to the sisters, but shortly before 1917, the apartment became the property of a stove-maker, Andrey Grigorievich Fedotov, who wasn't Jewish. He had many children, but gradually these children were leaving the family, and the owner and his wife died. Various tenants got accommodation in the apartment, and my parents received two smaller rooms when they arrived in 1922. My father's mother also lived with them.

Our family was the only Jewish family in this apartment. The others were Ukrainian and Russian tenants. There were no negative attitudes. All neighbors were friendly and supported each other. I was born in this apartment in 1923. My father's sister Nelly gave me my name, Naomi. When I was a child I was quite unhappy about this name because it was so different from other girls' names. My brother Samuel was born in 1928.

Before I was born my mother worked as a laborer at a plant, but after I was born she didn't go to work. My mother was a very good mother and housewife. We had a wonderful, cozy home, and my father and mother had a very warm and supporting relationship. My father adored my mother. They spoke Russian with each other and Yiddish with my grandmother.

I went to a kindergarten in the center of Kiev. I remember our teachers there: Katia, Sonia and Lucia. I felt very comfortable in the kindergarten. Once our music teacher recommended my mother to let me study music. She said I was talented, but my parents couldn't afford to give me a musical education.

There were many Russian classic books at home. My father and mother read a lot. My mother could play the guitar, and my father loved to sing. He had a beautiful voice and was very talented. He sang popular Soviet songs and arias from musical comedies. My parents also loved classical music. My parents had many Jewish and non-Jewish friends. We often had guests. They talked about literature and music, and sang.

My father's mother was the only religious person in our family. She prayed alone in the room in the mornings. She came from a religious family and observed all traditions since she was a child. My parents weren't religious, but they celebrated Pesach as a tribute to tradition. My grandmother cooked a very special borsch [beetroot soup]. There was matzah at home. My brother and I liked to have matzah with butter and salt and tea.

One of my brightest memories is seder at Pesach at my Aunt Maria's. Her husband, Efim, was a very religious man. We went to their family to celebrate once when I was 5 years old. I remember him sitting at the head of the table reading something long from a book in a language that I couldn't understand. There was a dish with horseradish, lettuce and chicken legs on the table. The table was covered with a snow-white tablecloth, and there was fancy tableware on it. We were supposed to eat a piece of everything on the table. Then I was asked to find a piece of matzah. I found it and then a big feast began with lots of traditional food: delicious borsch and Gefilte fish.

Our family was very poor, and we didn't have such a variety of food on holidays. Our usual food at home was soup for the first course and buckwheat for the second course. Sometimes, on holidays, my mother made beef or chicken chops and sweet and sour stew. She also made dumplings stuffed with cottage cheese. We never had pork.

We had simple furniture at home, and we wore plain clothes. I remember that a new dress was a great event for me. I remember my best dress - a cheap marquisette summer dress. My mother only had a few clothes and never wore make-up or jewelry. She had beautiful hair, but never made any great hairdos.

I began to study at a Ukrainian secondary school in 1931. I was very impressed with our music teacher, and when she first played a piece of music on the piano for us I was overwhelmed with emotions. Her fingertips touched the keys and filled the room with amazing sounds of music. I wanted to play like her.

My mother found me a piano teacher, and I went to her place to take classes. We didn't have a piano, so my mother found acquaintances that had one and agreed to let me play my drills. We went from one house to another so that I could practice.

In the summer of 1935 my mother took me to an audition at a special music school in Kiev. I heard one professor of music asking another one who had sent me to the audition. It turned out that all other children were children of venerable professors, and I was just a student of an unknown teacher of music. I was admitted anyway.

I was reluctant to leave my old school for this new one. I came there on the first day and went up the stairs gripping the banisters when I met my bosom friend Murochka from my former school. We happened to be classmates, and my tension vanished.

Our school was in a beautiful new building in the center of town. There were pianos in the classrooms. Most of the students were Jewish. There were a few non-Jewish children, but nationality didn't matter anyway. A concert hall with a big organ was built at our school in 1939. The school was located next to the Conservatory, and the two buildings were connected with a passage. Professors from the Conservatory lectured at our school.

I faced no anti-Semitism at that time. We were idealists. We were taught that our country was the only just and fair country in the world and eliminated exploitation of man by man. All nations had equal rights and so on. My friends and I believed it piously. We read Russian and foreign classic books and studied music. My mother's friends gave my brother and me a piano that they didn't need any more. We were fond of philosophy. We had a wonderful teacher: Valentin Valentionovich Popov. He taught history and philosophy in senior classes. We were very interested in issues about the sense of life.

The 1930s were the years of the horrific Stalinist repression [the Great Terror] 7, but I took little notice of what was happening around. When I came home after school I often saw my mother and father whispering about something with a troubled expression in their eyes. Then I noticed that I hadn't seen some of our neighbors for a while, but I didn't give it a thought. Books and music took up all of my time.

We didn't discuss fascism in our family, but we were aware of it. Some time before the war we watched a movie called The Oppenheim Family, but we didn't discuss it in the family. I believe, we were trying to preserve each other from negative emotions. [Editor's note: The Oppenheim Family, produced in 1939, was a film about the life and ruins of a Jewish family in fascist Germany by Russian director Grigori.]

I finished school in May 1941. A month later the Great Patriotic War began. My father understood that being a Jewish family we needed to leave Kiev as soon as possible. He had no illusions regarding the German attitude towards Jews.

My father worked at the Art Fund before the war. I don't know what he was exactly doing, but his boss valued my father much. In the first days of the war it turned out that my father was not subject to military service due to his age. His boss gave him a letter in which he recommended my father to potential employers as a very responsible and qualified employee.

We left on 2nd July 1941. We had very little luggage, as we were sure that we would return home soon. We had relatives in the town of Molotov [2,300 km northwest of Kiev]. They sent us a letter begging us to leave Kiev immediately. We couldn't take a train - they were all overcrowded. We took a boat down the Dnipro River to Kherson where we changed for a train. The train we took consisted of freight railcars for cattle or shipments.

There were five of us going into evacuation: my parents my brother, my grandmother Rivka and I. It was cold in Perm, and we were always hungry. We lived with our distant relatives. We were very close and supported each other. We didn't have warm clothes with us because we didn't think we would have to stay away from home for long, so our relatives gave us some of their clothes.

Many teachers of music were in evacuation in Sverdlovsk [500 km from Perm]. The rector of the Conservatory in Sverdlovsk, Abram Lufer, invited quite a few remarkable musicians to teach there. My teachers of music were there, too. They heard from students of the Conservatory that I was in evacuation in Perm and sent me an invitation to go to study at the Conservatory in Sverdlovsk. The invitation was approved by the management of the Conservatory and served as an official document for me to go there. During the war it was necessary to have passes to travel in the country. All residents or evacuated families had residential permits and were only allowed to travel with special permit documents.

I had never traveled alone. My parents were reluctant to let me go by myself, but my mother had a strong character. She decided that I should go to study in Sverdlovsk. My parents' acquaintances were in evacuation in Sverdlovsk, and they invited me to stay with them. We lived in a wooden barrack heated only by a small kerosene stove. We slept on plank beds. We only received a few grams of bread in exchange for coupons and were starving.

In August 1941 I went to work as a teacher of a junior group in a kindergarten. Later I found a job as a laborer at a plant from Kharkov that manufactured shells. We received 400 grams of bread per month. I wished to go to the front. I'm sure all young people were willing to go at that time. Later I got a job at a military plant. It gave me the feeling of being closer to the front and being able to make a contribution to the liberation of our country from the fascist invaders.

I lived in the barrack for a year and a half. I wanted to live at the hostel of the Conservatory and moved there in 1942. After I moved I fell ill with typhoid and then got pneumonia. I was ill throughout that winter, therefore I had to repeat my academic year. I went to the Conservatory as a second-year student the following year.

During the war my father's mother lived with my parents in Perm. They got a letter from some acquaintances informing them that the fascists had shot my mother's parents and four generations of her relatives along with other Jews in Rostov. My grandmother, who was very religious and prayed, lost her faith in God. She exclaimed that God wouldn't have allowed this to happen if He really existed.

Besides, my grandmother did something extraordinary. She wrote her will in Yiddish and hid it in her skirt. She told her children to follow her will after her death. She died in Perm in 1943. When the family opened her will it turned out that my grandmother bequeathed her body to the Medical Institute in Perm. She wanted to be of service to other people after her death. It was a very unusual thing to do. My father didn't dare to disobey and fulfilled his mother's wish. I came to Perm on business thirty years after the war. I found employees of the Medical Institute, who had worked there during the war, and remembered this unique event. They helped me to get an organ of my grandmother's body, which had been preserved in alcohol, that I buried at the Jewish cemetery. There was no Jewish community in Perm, and it was impossible to find a rabbi to bury my grandmother's organ according to the Jewish tradition.

My brother Samuel went to a music school, too, when he was a young child. He was very talented. He finished 5 years of studies before the war. In Perm he had an audition with Isaiah Brawler, a well-known Jewish teacher from Leningrad, who was an organ player. My mother took him to the music school after somebody mentioned to her that Brawler was teaching there. Brawler promoted organ music and was very fond of Bach. He auditioned my brother and admitted him to his class. He promised to teach him to play the organ after the war. Meanwhile my brother studied to play the piano, since there was no organ in Perm.

In 1944 musicians from Kiev were going back home, and I asked them to take my brother and me with them on the train. My brother had finished the music school and was preparing to take his entrance exams to the Conservatory. They agreed to take us. The train arrived in Kiev on the day after the fascists bombed the town for the last time. We were happy to return to our hometown.

On the first days after our return my brother and I went to Kreschatik, the central street. It was in ruins. We wanted to turn to Prorizna Street and get to Muzykalny Lane to find our school, but there were no buildings left there. There was only a sculptural portrait of Glinka 8 left, like a symbol for the lasting music.

My brother and I didn't have a place to live. We stayed at the hostel of the Conservatory, far from the city center. The town was destroyed, and there was no public transportation. We had to walk to the Conservatory. It took us about 40 minutes to get there. Music was our life, and having survived the war we were happy to be able to study.

Soon after we returned we went to the apartment where we used to live before the war. Our neighbors told us that our rooms were occupied by other people. At the end of 1944 our parents returned from evacuation. My father asked the people that occupied our apartment to move out and let us live in our apartment. He had a certificate confirming that this apartment had belonged to us before the war.

We were given a corner in a room. Other tenants had put up wardrobes, and we got accommodation behind these wardrobes. We didn't have any furniture left - it had been stolen or burnt during the war. Our neighbors gave us a folding bed, a sofa and a mirror. One neighbor had our table and low table for the samovar, another one had our sewing machine, which I got back. The hardest loss for us was the grand piano that my parents' acquaintances had given to us before the war. My brother and I were so upset that we decided to take every effort to find it. We asked everyone and did find it. Our neighbors from the first floor had it. They gave it back to us.

My father had all the necessary documentation and references from Perm he needed and promptly found a job at the Art Fund in the Conservatory. He was at work from morning until night. He was a clerk.

I remember the celebration of Victory Day on 9th May 1945. 17 of my parents' friends were sitting at our lopsided table. My mother made dumplings with potatoes and we had a real feast. Life was hard after the war. We ate millet with prunes or potatoes with prunes and bread. We bought cereals, potatoes and prunes at the market and received bread in exchange for coupons.

We had a great library before the war. There was nothing left of it. Many books were stolen. Besides, our neighbors used books to heat their apartments. I proposed to my father to stop collecting books, since we had no space for them. He seemed to agree with me, but after a few years we had a big collection again. My father couldn't help subscribing to publications or buying good books. He bought Russian classic books or works by contemporary writers.

In 1947 my brother received an invitation from his teacher Isaiah Bawler and left the Conservatory in Kiev to go to Leningrad. Samuel received a Stalin-stipend, a special scholarship that was only given to the best students. He graduated from two faculties: piano and organ. Later he also graduated from the post-graduate organ course.

In the late 1940s the policy of formalism and cosmopolitism began [the campaign against 'cosmopolitans']. It was actually a form of state anti- Semitism. I was very naïve, and at first I couldn't believe that an individual could be destroyed because he wasn't Russian or Ukrainian. Our teacher, Boris Liatoshynskiy 9, an outstanding composer and not Jewish, was among the first victims of the policy. He was fired and defamed. He was absurdly accused of formalism. Party activists called lyrical works that didn't openly call for the victory of communist ideas all over the world, formalism. This was why they destroyed talented people and replace them with whoever.

The next were our Jewish teachers: Liya Khimchenko and Marianna Geevik, a teacher of Western European Music and the Analysis of Musical Pieces. She was a very nice and interesting lady. They were both morally destroyed and fired. Some of them had to leave Kiev. There was a big meeting at the Conservatory, held by the party unit of the Conservatory. Former friends and students of these teachers criticized them. They called them citizens that didn't like their motherland and weren't patriotic enough. All these accusations were against Jews. I didn't attend this meeting. My friends didn't let me go there. They were afraid that I would speak in defense of my favorite teachers and would be dismissed from the Conservatory.

My father also felt the impact of the campaign. He was the head of a department at the Chamber of Commerce of the Art Fund. Akapian, the manager of the Chamber of Commerce, highly valued my father. When he was absurdly accused of not showing enough enthusiasm in the struggle for the ideals of communism, Akapian tried to defend him. He wrote letters to the party authorities, but it didn't help. My father was fired on the orders of the party authorities. He went to a high party official in Moscow to seek help. He was reinstated at work but not for long. Within some time he was fired again. He realized that he wouldn't be reinstated again. He found a job in a small office in Podol 10. My father was responsible for a department and successful at work.

In 1947, when I was a 5th-year student, my teacher took me to work in the evening music school which people called 'Conservatory for Workers'. This was the only school in Kiev where students, who worked during the day, could study in the evening. There were representatives of all layers of society, from the children of collective farmers to the grandson of a professor. Students had to pay a reasonable fee for their studies. It was very cold in the classrooms, and in winter we kept our coats on. Students had kerosene lamps and candles with them, since the light went out continuously. I worked at the school for 15 years. The students there were very inspired.

I remember blushing when I received my first salary. I was so fond of my work that I didn't understand why I was paid for doing what I liked best. I took my salary home and gave it to my parents. I only had one skirt and one blouse, but I was happy.

I graduated from the Conservatory in 1948. Israel was established in 1948, but I didn't take much notice of it. I was so busy at work and with my studies that I hardly thought about anything else. However, my parents were very happy about it. They discussed this event and were very enthusiastic about a new home for Jews.

In 1953 Stalin died. It was such a blow to me that I fell ill. Like many other people I believed that Stalin was an exclusive man and that nobody could replace him. I remember that I felt like killing anyone who was glad that it had happened. I even submitted my application to become a member of the Communist Party, but in the course of my illness my passion faded, and I didn't join the Party in the end. My mother and father sympathized with me and repeatedly said that someday I would understand. They hoped that Stalin's death would put an end to the period of repression and that the Soviet people would be able to enjoy freedom. After the war many of my friends got married. I had admirers, but none of them was 'Mr. Right'. Besides, many of them were not Jews, and I wanted to marry a Jewish man. My parents raised me with the conviction that a Jewish woman should only marry a Jewish man. So I decided to stay single. I've never regretted it.

We had a radio at home that only broadcast regular Soviet programs. In 1973 my father's friends gave him a multi-channel radio for his birthday, and we began to listen to the Freedom and German Wave stations. We closed the door to keep it a secret from our neighbors. If one of them had reported to the KGB that we were listening to these stations, we might have faced problems and even been arrested. We got a TV much later than all our neighbors. My mother had poor sight, and my father believed that it would do her no good to watch TV.

We read many samizdat books in the 1970s. [Editor's note: the term samizdat comes from the Russian 'sam' for 'self' and 'izdatelstvo' for 'publishing', it was derived from the official Soviet Gosizdat, the State Publishing House.] Samizdat literature was privately and illegally produced and circulated in the Soviet Union after Stalin's death. Before glasnost in the 1980s, this was the only way to publish anything not endorsed and censored by the government. Our parents' friends used to bring those publications to us secretly. When the weather was good we took folders with these books, which were printed on standard sheets, to read them at the bank of the Dnipro River. We read Solzhenitsyn 11, Bulgakov 12 and many other authors.

Neither my parents nor I observed Jewish traditions. My mother died and in 1975 and my father died in 1978. They were buried in the town cemetery.

In 1962 I went to work at a different music school. I taught musical literature. I never thought it could be so wonderful to teach children. I was dedicated to my work. I teach children to listen to music and understand it. They also need to know the history of music and musical genres: songs and romances, operas and symphonies. My main concern has always been music. Our friends and my students often came to our apartment at weekends, and we talked about music and played the piano.

My brother Samuel went on organ concert tours all over the Soviet Union. In the 1980s he moved to Lvov and worked at the Conservatory until his death. He was married. His wife Yadia, a Jewish woman, was also a musician. They got married after they were working together at the rehearsal of a concert for two piano players. Their son, Dmitriy, was born in 1953. He lives and works in Rostov now. He is a musician, an honored artist of Russia, professor and head of a chair at the Conservatory.

My brother died in Lvov in 1990. His wife died a few years later. They were both buried in the Jewish cemetery in Lvov. The loss of my brother was a tragedy to me. I felt like he took care of me. He called me once in a few days and always supported me. Back in the 1940s our parents had told him that he was responsible for me throughout his life. He bore this responsibility until the end of his life. I felt like my childhood was over when he died.

Now, at 79 years of age, I lead a very active life. I go to work at the same music school twice a week. My friends and my former students come for a cup of tea every now and then. We talk about music. Some of them are 20, some are 50 years old.

A few years ago a company bought the communal apartment where I had lived since the late 1940s. They offered me a two-bedroom apartment in the city center. Only then did I understand how wonderful it is not to have neighbors in your apartment.

I am very enthusiastic about the revival of Jewish life. I like going to concerts of Jewish music and exhibitions of Jewish artists. I read books about Jews and Israel, translated from Hebrew and other languages. Such books weren't available before. Older people from Hesed often get together in my apartment on Jewish holidays. We celebrate Pesach and Rosh Hashanah. I have a new TV at home, which was given to me by Hesed. My curator gave it to me after she visited me at home. I also receive food packages from Hesed.

Israel was a distant country to me, but after my friends started moving there I felt like getting more and more information about it. I ask my friends to send me books about Israel, and they do. I wish I could visit this country. I'll never leave Kiev though. This is my hometown, and I don't think I would be able to live elsewhere or that I would be needed anywhere else.