Liza Lukinskaya

Vilnius

Lithuania

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: February 2005

I met Liza Lukinskaya in the Jewish community of Lithuania. As usual she came there to see her friends and discuss topical issues. Liza is a stocky, fashionably dressed woman with neatly dyed hair. She appeared to be outgoing and agreed to be interviewed at once. We met for the second time in Liza’s apartment in one of the relatively new districts of Vilnius. She lives in a house, similar to the Soviet buildings of the 1960s. Liza lives in a good three-room apartment with light wall-paper and fancy curtains and flowers that reflect the character of the owner: kind and easy-going.

My family background

Growing up

During the war

After the war

Glossary

My paternal grandfather, Leizer Abramson, was born in the middle of the 19th century in Kaunas. He was a merchant. He owned a small furniture store in the center of the city. His business was rather lucrative. Grandfather’s family was rich and they had their own house in Kaunas. Grandmother Hana-Beila was eight years younger than him. In accordance with the Jewish tradition she got married at a young age and became a housewife, taking care of their home and raising the children. I didn’t know Grandfather Leizer. I didn’t live to see him as I was born in 1920. At that time the whole family – grandparents, their adult children and their families, young single children – were exiled from Lithuania. When World War I started, the tsarist government exiled Jews from frontier territories. My grandfather’s family happened to be in Ukraine, but I don’t know where exactly. Grandfather died there in either 1916 or 1917.

I heard that Grandfather was a religious person, but not a zealot. He observed Jewish traditions, celebrated holidays, went to the synagogue and had his own seat there. I remember grandmother Hana-Beila. When the family came back to Lithuania, on holidays she came from Kaunas to Siauliai, where one of her daughters lived. Grandmother seemed very old to me. I remember that she prayed in the mornings. On Fridays she and I lit the candles on the eve of Sabbath. Grandmother didn’t cover her head, but as for the rest she totally looked like a traditional Jewish woman. She died in the early 1930s in Kaunas and was buried at the Jewish cemetery there.

Leizer and Hana-Beila had ten children – four sons and six daughters. All of them got traditional Jewish education. The boys finished cheder, then lyceum. I don’t know anything about the education of the girls. Anyway, the children of Leizer and Hana-Beila were literate people. By the irony of fate none of the daughters had children, and the brothers had two or three children. All of my father’s siblings perished during the Fascist occupation. First Hana-Beila gave birth to daughters. Then the boys were born. The eldest sister Ida, born in the late 1870s, helped her mother raise the younger children, and rejected all her fiancés. Ida remained a spinster. She never worked and lived with grandmother Hana-Beila.

When her mother died, Ida moved to her sister Fanya, who was one or two years younger. She was a famous milliner. Fanya owned a large hat store and atelier, where she and a couple of dozens of her employees made beautiful, fashionable hats. All the stylish ladies from Kaunas knew Fanya. She was married. Her husband, a Jew, Keirauskas was deported 1 and exiled to Siberia in 1940. It saved his life. Ida and Fanya died in the Kaunas ghetto 2. Ten years after the Great Patriotic War 3 Keirauskas came back to Lithuania. I don’t know what happened to him. After Fanya died he didn’t keep in touch with our family.

Liza, born after Fanya, was also married. I don’t remember her husband’s name. He died before the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. Liza also perished during one of the first actions of extermination in the second Kaunas ghetto. I don’t remember my father’s other sisters. Our family rarely kept in touch with them. I know that one of them, the youngest, stayed in Ukraine. She remained single and died at a very young age.

My father was the eldest of the brothers. Then Abram was born in 1890. He was a violinist and worked in the orchestra of the Kaunas opera theater. I don’t recall his wife’s name, but I clearly remember his children’s names. The eldest, Israel, was my age. Before World War II he was a student. The younger Lev and Anna went to a lyceum. Abram’s family perished in Kaunas ghetto during its liquidation in 1944.

Samuel Abramson, born in the 1890s, followed Abram. He was a representative of a large trade shoe enterprise, Salamander, in Kaunas. This enterprise is still known all over the world. He ran the Salamander store in Kaunas. I don’t remember the name of his wife and two children. They also became Nazi victims in Kaunas ghetto. My fathers’ younger brother, Yakov Abramson, born in the 1900s, and his wife owned a hat store in Kaunas. Both of them ran the business. They had two sons, who perished in the ghetto with their parents.

My father, Isaac Abramson, was born in 1887. Having finished cheder he went to one of the Jewish lyceums of Kaunas, though I don’t know how many grades he finished. He was exiled to Ukraine with his family and in 1917 met my mother, who was from Romny, Sumy oblast [about 250 km east of Kiev]. Father also lived there at that time.

My mother’s parents were from Ukraine. Most likely they were born in Romny in the 1870s. Mother’s father, Tsal Dubossarskiy was also a merchant. He was very rich. I don’t know what exactly his business was. I didn’t know Grandfather – he died in 1922 after our family came back to Lithuania. Grandmother Anna was a housewife and brought up the children. After her husband’s death Anna moved to Kharkov [440 km east of Kiev], where she lived before the beginning of the Great Patriotic War. During the war my grandmother was in evacuation in Ural. When the war was over, she came back to Kharkov. After the war she lived only for two years. I didn’t see her then and was not able to find out about her life.

My maternal grandparents observed Jewish traditions and celebrated holidays as did the paternal ones. They also went to the synagogue, but in my mother’s words they did it because it was customary for the Jews, not because of their religiousness. They tried to raise their children – two daughters and three sons – to respect Jewish traditions, but they kept abreast with the times. Mother told me that they had governesses who taught them foreign languages and music.

I didn’t know my mother’s brothers and their children. I don’t remember the names of all of them. The eldest brother Alexander, born in the early 1900s, was a callow youth, ran away from home during the Civil War 4 and joined a Red Army squad. He fought in the cavalry and became a Bolshevik 5. When the Civil War was over, he finished the Construction Institute in Moscow and worked as an engineer at some military plant. He lived in Moscow all his life. He was appointed to high positions. Alexander had a son, whose name I don’t remember. He also lived in Moscow. Alexander died in the 1970s.

The second brother, Aron, who was one or two years younger than Alexander, was a career military. He went through the entire Great Patriotic War and then lived in Kharkov. He died in the 1980s. The youngest, Yakov, also lived in Kharkov. He worked as a chief accountant of some pharmacy administration. He was in evacuation in Ural and after the war lived with his wife and children in Kharkov. He survived Aron by a couple of years.

My mother’s only sister Katya was much younger than she. I have a picture, where teenage Katya held me in her arms. I was four months old in that picture. I don’t remember Katya. She stayed in Ukraine. She died from pneumonia in about two years after we had left. She was only 17.

My mother, Feiga Dubossarskaya, the eldest in the family, was born in 1898. She obtained a wonderful education. She finished a Russian lyceum. I don’t know what language was spoken in the family of Grandfather Tsal. My mother was proficient in Russian, both oral and written, but she didn’t speak very good Yiddish and had an accent. Mother was taught music and played the grand piano. She was good at it. I don’t know how my parents met. In 1917 they got married. They didn’t have a traditional Jewish wedding. It wasn’t the right time: the years of the Revolution 6, Civil War, hunger and pogroms 7. In 1918 mother gave birth to my elder brother Abram, and on 13th May 1920 I, Liza Abramson, was born. By that time Lithuania had gained independence from Russia 8. Many Lithuanian citizens came back to their motherland and in 1921, when I was a year and a half old, our family – my mother, father, brother and I – came back to our motherland in Kaunas, which was the capital of Lithuania at that time. Almost all of my father’s family came back there.

Here in Kaunas my parents rented a small two-room apartment on the outskirts. I have some vague memories from my childhood in Kaunas. I remember a big round table, a large parental bed and beautiful velvet window curtains. Once, my mother asked me to give her a pair of scissors. I took them and ran to the sofa, where my mother was sitting. I fell down on them and hurt my neck. I still have a scar. I was a bad trencherman and my mother was constantly trying to scare me with gypsies. I was afraid of them for many years. When I was five or six, Father was offered a well-paid job and our family moved to Siauliai [about 200 km from Vilnius].

Father was assigned to a good position. He was a representative of the owners of the Guberniya brewery. This company is still an important brewery in Lithuania. Father was a very gifted and literate man. He was fluent in Russian and Lithuanian, both oral and written. He also knew Polish and German. He had a lot of responsibilities: starting from concluding contracts with stock houses and stores and up to quality control of beer. Siauliai was the second city in Lithuania after Kaunas in terms of population and importance. It was multinational. 30-40 percent of the population was Jewish.

I was a feeble child. When I was unwell, the pediatrician Kantorovich came over. There was also a doctor at the plant where father was working. He was a Lithuanian. He was also called, when needed, and treated our family free of charge. There were a lot of Jews in Siauliai – merchants, businessman, intelligentsia: doctors, lawyers, teachers of Jewish schools. There were two synagogues in the city. The first place we lived in was near a large two-storied synagogue, located in the vicinity of the train station. My father went to the synagogue at that time and took my brother and me with him. I liked to see my father change in the synagogue. Usually he was funny and kind. When he put his tallit on, he looked older and stricter.

There was an old building of a confectionary in front of our house. So it smelled like sweet caramel in our block. There was a military unit and an orchestra in the yard of our house. My brother and I enjoyed listening to bravura marches and waltzes they played almost every day. Our apartment was rather small, consisting of two rooms: my parents’ bedroom and the room I shared with my brother. At first, it seemed to me that father didn’t make that much money in Siauliai, as my mother did the house chores and cooking.

Soon Father was given an apartment near the brewery and we moved to a new place. The office of the brewery was located in the former mansion of some respectable countess. It was a beautiful two-storied building with a yard, fence and a gate. There was a 24-hour security guard by the gate. It was closed for the night and the guard would walk around the yard with a dog and didn’t let in any outsiders. The office of the brewery was on the first floor together with the small premises of a music school. There were several apartments for the employees of the brewery on the top floor.

We had a four-room apartment. My parents purchased new furniture. There was a beautiful carved cupboard in the drawing-room as well as a table, chairs and a sofa with silken upholstery. The bedroom furniture was made from nut wood – a wide queen-size bed, mirror, dresser and large wardrobe with a mirror. There was not too much furniture in the small dining-room: a table with chairs, a small round table, where the telephone and address book were placed. Mother embroidered very well and she decorated the room with embroidered pictures and cushions and white starched laced table-cloths.

Father started making pretty good money and we felt it. We acquired a beautiful grand piano made of mahogany. Mother played it. My brother and I were taught music at home. Besides, I had an English tutor, who came over to us. We had a housekeeper: a Russian lady, Nina, but my mother, a great cook, didn’t let her cook without her guidance. She spent a lot of time in the kitchen. Food was cooked on primus stoves – there were several of them in the kitchen. There was also a stove, where Mother baked different pies, cakes – tartlets, rolls and all kinds of desserts. I still consider her cake ‘Napoleon’ to be the acme of culinary art. Mother cooked Jewish and Ukrainian dishes. She made wonderful borscht with garlic pies, vareniki [a kind of stuffed dumpling] with meat stuffing, curds and potatoes. Puffy meat patties were always served with broth. I don’t know what kind of cuisine that is.

We had all kinds of modern novelties in the kitchen. In that period of time people started canning food. Father bought a German apparatus with jars and glass lids. Mother made stewed fruit and canned them. Then she put them in a special boiler. We had a fridge in the kitchen: a special crate, where a metal box with ice was put. The ice was brought from the brewery. When it melted, more ice was brought again in a couple of days. There was a special cooler for pickles in the cellar. Father made them. He salted tomatoes, cucumbers, cabbage in large barrels and stored them in the cellar.

My parents mostly spoke Russian at home. Mother knew Yiddish, but Russian was closer to her. Of course, I understood Yiddish as my father tried speaking it with me. There was a Jewish school by the synagogue and my brother and I went there. I went to that elementary school for two years. Subjects were taught in Yiddish. There were several Jewish schools and lyceums in Siauliai. When I grew up a little bit, Father made arrangements for my brother and me to be transferred to the Jewish lyceum. Here I started studying a language that was new to me: Hebrew. It was a prestigious institution. Father had to spend a lot of money on my tuition. I don’t remember the precise amount.

The lyceum wasn’t far from home. My brother’s friend lived close by. His parents owned a cab and they usually gave us a lift with their son. Once, in winter time, when it was frosty, the three of us came to the lyceum, but my brother and I weren’t let in. It turned out that Father left on a trip and didn’t manage to make the payment. My brother and I had to walk back home across the town. When Father came back, he was furious. I had never seen him in such a frenzy. He went to the lyceum right away and took our documents. The headmaster of the lyceum understood his fault and tried to correct the situation. He came to my father with his apologies, but Father wasn’t willing to listen. He hired teachers for us, who came home and crammed us for the Lithuanian lyceum. In summer 1929 my brother and I entered it rather easily. He went to the boys’ and I went to the girls’ lyceum.

Father’s friends also belonged to the middle class. As a rule, husbands worked and their spouses were housewives. Mother’s friends came over every once in a while. They had tea or coffee with Mother’s pies, browsed fashionable magazines and played cards. Women met once a week. Each of them received guests in turns. Sometimes they went out to eat ice-cream and drink liqueur. Mother often took me with her. She was a fashionable lady. She had her clothes made by the best milliner in Siauliai. She enjoyed shopping. She liked stores that sold readymade goods and haberdashery. Mother always went to the store where threads, yarn and knitting needles were on offer. The owner of the store gave classes on needlework to beginners.

On weekend our whole family often went out together. There was a central park in front of our house. It was shady and beautiful. There was a chestnut alley not far from it. In summer Father rented a dacha 9 for us a room and veranda in Pagegiai [about 200 km from Vilnius]. It was a splendid place, with seven lakes in a row. Mother was good at kayaking. Every day she and I swam in the lakes. Sometimes she put us in the kayak. My parents were great swimmers. Special belts were made from corks for my brother and me. Soon we also learned how to swim. As a rule Father came over to us for a weekend and we had picnics in the garden or in the forest.

My parents weren’t religious, though they kept up the traditions. Meat was bought only in kosher stores. Chicken and other poultry were always taken to a shochet. Sometimes Mother bought a tidbit-pork ham. She kept it in paper and gave it to me and my brother when nobody was around so that the neighbors wouldn’t see. When I said that we couldn’t eat pork, Mother gave me a surprised look and said, ‘Where do you see pork, it’s ham!’

Sabbath wasn’t celebrated at home the way it was in traditional families. Though, my mother did her best. She baked challot, put wine and candles on the table, lit the candles herself. On Saturday there was always a festive dinner, but Father didn’t go to the synagogue, moreover he had to work as Saturday was a working day at the brewery. Only when Grandmother Hana-Beila, who celebrated Sabbath, came to us from Kaunas, the whole family was at the table, and Grandmother said a prayer. Grandmother died in the early 1930s. I was very sick at that time and Mother couldn’t leave me. Father went to his mother’s funeral by himself. Grandmother was buried in accordance with the Jewish rites. The mourning period was also observed.

We celebrated Jewish holidays at home. I remember Pesach best of all. The house was prepared for the occasion well in advance: cleaning, dusting, polishing, dressing the windows with beautiful curtains, putting a beautiful table-cloth on the table. The dishes were well taken care of. There was a special set of Pascal dishes, stored in a certain cupboard. The rest of the dishes were given to some Jews to make them kosher: they soaked them in some tub and then deterged them with sand. Matzah was brought from the synagogue in a large hamper covered with a cloth. No special rites in connection with the banishment of chametz were conducted in our house. I asked Father the four traditional questions, as I was the youngest in the family, during the first seder.

There were all traditional products on the table: eggs, potatoes, some bitter herbs etc. Of course the table was lavishly laid with festive dishes, cooked by my mother. She cooked delicious kneydlakh made of onion, fried with chicken and goose fat, eggs, matzah flour and chicken broth, boiled in chicken broth. There was always gefilte fish, chicken stew and all kinds of tsimes 10. Mother cooked great imberlakh – a Jewish dish, made of carrots and ginger, boiled with sugar before thickening, put in layers on the board and cut in different shapes. Mother also baked cake from beet with nuts, a scrumptious sponge cake from matzah flour. Well in advance Father made wine from hops, honey and raisins. Mother also made teyglakh – honey and sugar boiled in syrup with ginger and a pinch of lemon acid, made in different shapes: rolls and spirals.

For Purim my mother always baked very tasty hamantashen with curds. On those days Jews brought presents to each other – shelakhmones. Trays with desserts were brought to us from Mother’s friends and she sent presents in her turn. A chanukkiyah was lit at home on Chanukkah. It was put in the window in accordance with the traditions. Potato fritters were also made. There was a feast in the evening.

I vaguely remember the fall holidays. When we were living in the old apartment by the synagogue, there was a sukkah made by the neighbors in our yard and we also went there. I remember the holiday of Simchat Torah when Jews would joyfully carry the Torah scroll. My brother and I were able to watch those holidays, when we were living by the synagogue, but those holidays weren’t celebrated at our place.

In 1935 Mother received an invitation from my grandmother. She had all necessary documents processed and went to see her in Kharkov. Her brothers, who were serving in the Soviet Army, were Communists. They didn’t know about her visit. When Mother came to Kharkov, Grandmother sent them a telegram saying that she was severely ill and asking them to come. Mother’s brothers saw her in secret. If it was known that they had seen their sister, who was living in a capitalist country, they might have shared the fate of the thousands of those repressed 11 by Stalin. Moreover, they didn’t even talk about their mother.

When I became a student of the Lithuanian girls’ lyceum I was mostly in a female environment. I was the only Jew in my grade. Actually, another Jewish girl joined our grade two years before my graduation. I was friends with Lithuanian girls: Polina Uskaite, Gribaite, Lukasheite. We were friends for ages. My classmates, both Lithuanian and Russian, treated me very well and paid no attention to my nationality. There was only one teacher, Vishinskine, who was an ardent anti-Semite. Even during the classes that had nothing to do with ethnicity she blamed Jews for all kinds of trouble. I was very active and sociable. The girls liked me. My friends and I went for walks in the park. We gave each other hugs. Sometimes we went to cafes to eat ice-cream, watched movies. There were two movie houses in Siauliai at that time. There was the Lithuanian Drama Theater. I liked to watch performances there. I liked everything, connected with the theater and the stage. My dream was to become a ballet-dancer. I loved amateur performances. I danced on the school stage, played the grand piano and accompanied singers on the piano. I felt like fish in the water.

In the last but one grade we had a Judaic class. Less than ten students out of the entire lyceum attended that class. When I was a junior student I was a member of the Lithuanian scout organization Ptichki. I never joined the scouts for senior students. When I was a senior student, I started seeing boys. I went out with a Lithuanian boy, Eduardas Kudritskas. It even seemed to me that I fell in love with him. At home I even started bringing up the subject of marrying him. Then my parents said that they would marry me off only to a Jew.

My brother Abram didn’t do very well at school. Starting from the fourth grade Father transferred him to a Yiddish lyceum where it was easier to study. But Abram had a talent for music. He started playing the accordion, the piano. In 1938 he was drafted into the Lithuanian army and he served in a musical squad in Siauliai.

I succeeded at school and in 1938 I graduated from the lyceum ranking among the top students. I wanted to become a doctor. In order to enter the Medical Department at Kaunas University I had to take an exam in Latin. We had studied it only for two years and I was afraid that I wouldn’t pass it, so I decided to enter the Biology Department. I could enter it only via an interview and then get transferred to the Medical Department in a year, which wouldn’t be complicated. I parted with my friend Eduardas and left for Kaunas. Soon I forgot about him. Puppy love goes by very quickly. I settled at the place of my Aunt Fanya, my father’s sister. The first years flew by very quickly.

During that time certain political changes in the country affected our family. Father, a respectable man, who had worked at the brewery for a long time, got a mild hint to leave his post due to an anti-Semitic wave. He wasn’t fired. They let him choose any Lithuanian city where he could be in charge of the stock of the brewery. Thus, my parents left for the small town of Skaudville [about 200 km from Vilnius]. Father’s salary barely changed, but he suffered morally from being unjustly laid-off.

In 1939 I submitted my documents for a transfer to the Medical Department. The 1st-year-curriculum of our faculties was identical. All I had to do was to go though a physical check. The medical board declared me unqualified for a doctor’s career, though I was healthy, while my Lithuanian friend, who was afflicted with tuberculosis, was enrolled in the Medical Department as per resolution of the same board.

In that period of time Fascist youths appeared in Lithuania and a vexing incident took place at our institute. In a chemistry lecture, those youths demanded from a Lithuanian professor, who was holding lectures for two faculties – Chemistry and Technology, to make Jewish students take separate seats at remote desks. The professor refused and said that all students were equal at his lectures. There was a terrible scandal, the professor had a heart attack and was taken to hospital immediately. Neither he, nor the rector of the institute conceded to the gangsters.

I was a good student, besides I didn’t have to pay practically anything for it. My brother was transferred to another town, not far from Skaudville. We tried to use any chance to visit our parents, be it vacation or holidays. During one of my brother’s leaves, which concurred with my holidays, both of us went to Palanga. It was a wonderful month: warm, care-free and we were sporting on the coast of the warm sea, mixing with people of our age, going dancing and to the cinema.

In June 1940 the Soviet Red Army troops came to the Baltic countries and Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia were annexed to the USSR 12. Many poor Jews hoped for a better life and they welcomed the Soviet soldiers as liberators with flowers. Other rich Jews and Zionists 13 stood still, awaiting trouble, which soon came. Many of them were exiled to Siberia. My parents took it as a mere fact, but their life changed as well. There was a tank division with the families of the soldiers on the border with Germany, in Skaudville. My mother, a funny and sociable woman soon made friends with those ladies. She played the piano in the army club and militaries often came over to my parents’ place to listen to music and have a good time.

Our class was transferred to Vilnius University. I moved into the hostel. I had a modest life like any student from another city. As earlier, all subjects were taught in Lithuanian. We started studying Russian, which was familiar to me as my mother spoke Russian with my father. The Komsomol organization was founded 14, but I didn’t manage to join it.

The last year of peace before the war brought me joy and love. I met a wonderful Jewish lad. We fell in love with each other. Ilia Olkin was born in 1919 in the Lithuanian town Panemune. His father, David Olkin, was a pharmacist. He had his own pharmacy in the town. Ilia’s mother, grandmother and three younger sisters lived in Panemune as well. I can’t remember their names now. All of Ilia’s relatives perished during the German occupation. We started seeing each other and spent almost all our time together as Ilia also lived in the hostel. Soon Ilia became the leader of the Komsomol organization of Vilnius University. He was one year my senior. He was working at the chair and dreaming of post-graduate studies. Ilia came to Skaudville with me and asked for my hand in marriage. My parents liked him very much. Having met my parents, Ilia introduced me to his. Thus, the first year of my first true love had passed.

In late May 1941 my brother was demobilized. He came to Skaudville. Having passed our exams, Ilia and I were on the verge of going to my town to see my brother and discuss our wedding, but fate dictated different things. In the night of 22nd June Vilnius was unashamedly bombed. First we decided that it was some civil defense training, which we had got used to in the previous year. Soon, it was clear that the bombs were real. There was fire after the bombs had been released. I tried calling home, but there was no connection. On the second day I, Ilia and three of his pals decided to leave. We took some necessary things and documents – we had hardly any money as we didn’t manage to receive our scholarship – and went to the train station. It was hard to get there. The trains weren’t leaving. Then we decided to walk towards the East, to Russia. I remembered that my grandmother Anna lived in Kharkov, on Feurbach Street, and Mother often told me that I had to go to Granny in the event the war started.

We were walking on the road along with thousands of people. People with babies and old men, who could barely walk, were on carts. Many were going on foot in the Eastern direction. The Soviet troops were retreating with us. It was accompanied with bombing, during which people hid away in the bushes by the road and in ditches. After the bombing not all of them came back to the road. It was dreadful and seemed interminable. We were let in some places to spend the night. We didn’t have money and Ilia’s pals paid for us. They were much older and had money on them. On our way retreating soldiers in passing cars told us that the Germans had entered Vilnius.

We reached Belarus – I remember the name of a village: Berezovki near the town Kobylniki [150 km from Minsk]. We stayed with local peasants, whom our friends paid good money. We had stayed with those people for about a week until the moment when some of the retreating Soviet soldiers said that if they sheltered Jews, the Germans would shoot them. The host took us to Kobylniki in a cart. There we stayed for a couple of days at the place of a local Jew. We saw Fascists there. The next day there was the first Fascist action. They demanded all members of the Communist Party and male Jews to step out into the square. On that dreadful day Communists were shot and Jews were ordered to bury them. Ilia and his pals were also there. In the evening they told us about it with horror. One of the men was shocked. He didn’t see any way out and decided to hang himself. I, the only woman in our company, turned out to be the most decisive. I said that we wouldn’t be staying there any minute longer. We had nowhere to go and we decided to return to Lithuania – be it as it may, at home even walls seemed more helpful.

In spite of the curfew hour, we went out of town through back yards and alleyways, reached the forest and spent time there. On the way back we walked mostly at night, trying to be as inconspicuous as possible. Sometimes we were given a lift, but still we walked most of the time. A couple of times we asked some people to let us spend the night in their farmstead, but none of the hosts let us in. I can’t blame them and I don’t think they were anti-Semites. The order of the Fascists had already been conveyed to the population and they knew that they would be shot if they sheltered Jews.

So, we reached Vilnius. Our dear and favorite city bode danger. Fascists and Lithuanian polizei 15 were all over the place. We were told that the polizei were looking for Ilia as he was the secretary of the Komsomol Committee. We decided to leave Vilnius and go home. We were lucky: some cart heading for Kaunas took us. There were 25 people in it. We reached some farmstead in the vicinity of Kaunas and a police patrol stopped us. All the Jews were told to leave the carts. I started explaining that we were poor students on our way home and besought them to let us go. I succeeded in that: we were the only ones whom they let go. I don’t know why, but during the years of occupation I was really lucky when I was about to face death. It was the first time of my luck, and you will be able to see other spells of luck further in my story. We were released and we ran after that very cart and got on it. We were detained in the vicinity of Kaunas. It was horrifying as that time we were stopped by the Fascists and again I talked them into letting me go. Ilia was arrested. I could only shout to him that I would be waiting for him in Kaunas at Aunt Fanya’s place.

Aunt Fanya was alone. Her husband was exiled to Siberia one month before the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War. Aunt Fanya had a forlorn hope to see me alive. She told me that all men were shot and I should not hope to see Ilia again. She also said that somebody in Siauliai saw my parents and brother on the truck with the wives and children of the militaries. As it turned out later, our family was saved thanks to Mother’s hospitality and cordiality. Military guys and their wives loved her and when the war was unleashed, Russian militaries came to our house and sent our family in evacuation together with their wives. I found out about that after war. Now, when my aunt said that parents had left, I felt better. At least some members of our family could count on being rescued.

I understood that I had no place to go in Skaudville and stayed with Aunt Fanya. The first evening I stayed with her, a gypsy came over to read the cards as Aunt Fanya was very worried about her husband and started believing gypsies. Aunt, who had never believed neither cards nor fortune-telling, talked me into cartomancy. That lady spread out the cards and told me about all my life. She said that I was worrying about one young man, who was detained and that he would come to me in three days. Two men and one woman were on a long trip, also thinking and worrying about me. I would also meet them, but in three or four years. All those things came true.

Ilia came back in three days. He survived by a miracle. He was taken to prison, where Jews were detained before getting shot, but it was packed. The drunk polizei didn’t want to bother, kicked him on his back and let him go. We started living at Aunt Fanya’s place. Daily hazards and adversity made us close and we practically became like husband and wife. It was dangerous to appear in the city, especially for young men. Every day they were caught and executed. We didn’t want to venture out again. I went out to get some scarce products for our food cards. There was a curfew hour in the city, and it started earlier for the Jews than anybody else. I took silver spoons my aunt gave me to the commission shop. When they were sold, I wasn’t given any money and told instead that Jews needed no money as soon all of us would be murdered.

In July it was announced that Jews were to settle in the ghetto. First there were two ghettos – a big and a small one. There was an overhead crossing connected to the small ghetto. There were vehicles on the road and people were walking in the streets, while we were prisoners and forbidden to leave the ghetto territory without a guard. Aunt Fanya and I were in the small ghetto. My husband and I lived in one small apartment with Aunt Fanya and Aunt Ida, who moved to the ghetto with us, and some strange woman, who wanted to join us.

All ghetto prisoners were supposed to work. I and my husband did digging work at some construction sites at the aerodrome in a crew of young and able-bodied people. We were escorted by Jewish policemen on our way to work. All prisoners had yellow hexagrams on the back and on the chest. A Judenrat 16 was founded in ghetto, which was in charge of all vital issues and followed execution of the orders of the commandment. There was Jewish police in the ghetto. All craftsmen, tailors, cobblers and tinsmiths, who could be of any use, were issued working IDs.

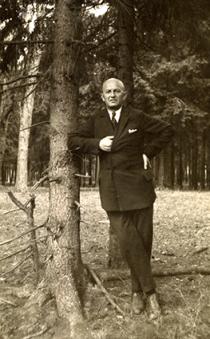

The Fascists even had an orchestra in the ghetto, where Uncle Abram was playing. There is his picture with several members of the orchestras of ‘die-hards.’ My aunts Fanya and Ida didn’t have anything: they were housewives. In about a month Fascists made a tentative action: they cordoned off the ghetto, placed machine-guns on the bridge and ousted everybody from their houses. We stood in the square for a long time, and the Fascists just mocked us and let us go. When in a while the same situation happened again, everybody was relatively calm, thinking that they would let us go after taunting us. Nothing of the sort: it was the most dreadful action on liquidation of the small ghetto – on that day the Fascists sent ten thousand Jews for execution. On that day I didn’t go to work as I felt unwell. Ilia happened to be in a crew at the aerodrome and they were permitted not to return to the ghetto as the next working shift wasn’t released from the ghetto. I was waiting for my husband by the gate and crying, without knowing whether he would come or I would have to die alone. My Ilia came back, he couldn’t part with me.

They started classifying people: craftsmen were set aside. All of us – my husband, I and three elderly ladies – turned out to be among those who were to be taken to nowhere. At once I darted to the policemen and said that my husband and I were young and could work, and added that we were working hard at the aerodrome and would work even harder. He separated me and Ilia with the butt of his gun. We were taken to the big ghetto with a small cluster of craftsmen. In the morning we saw my aunts Fanya and Ida being taken to get shot. Then we were allowed to come to the small ghetto and take some things. I found something: a brown coat with a fur collar, given to me by Aunt Fanya, was hanging on the fence of our house, the place where I left it before the action. I took my coat and it served me for a long time, keeping me warm in wintertime, during the occupation and preserving the memory of a dear person.

We started living in the big ghetto. We could only leave the ghetto on our way to work. We settled in the place of my Uncle Abram Abramson, who had been a violinist before the war. He had a good house in Kaunas and they were given three rooms in the ghetto. Almost all musicians perished after the liquidation of the small ghetto and the orchestra didn’t exist anymore. Uncle Abram was involved in hard physical labor like all men. I lived in Uncle’s apartment by myself, and Ilia found lodging at the place of his friend. The matter is that my uncle’s wife was a greedy woman and constantly was rebuking me for eating their daily bread. Once I finished working late at the aerodrome, came home and turned on the light in the kitchen to cook some food. My aunt came in and said that I shouldn’t waste electricity at night and turned off the light. The next day I told Ilia that I wouldn’t stay with my relatives any longer. He found a room where a guy, whose entire family had perished, was living. We moved in with him. In a while Ilia and I registered our marriage at the Judenrat. In the evening we had tea with bon-bons. That was the way we celebrated our wedding.

Food was the most vital problem in the ghetto. Ghetto dwellers, who managed to keep some precious things, exchanged them for products. We had nothing: we left Vilnius empty-handed. We earned our daily bread this way: old people, who had no chance to leave the ghetto, gave us some things to exchange for products and told us what they wanted to get, we received the surplus. E.g. from exchange they wanted to get a loaf of bread or a certain quantity of grain, and what we got in excess of that belonged to us. My husband even managed to get caramel for me. I had a sweet tooth and there was some underground store in the ghetto where he bought me candies. I don’t know how the owners of the store managed to get products. They most likely had their person in the police.

The second problem was work, which was very hard. We had to work under any weather conditions: in terrible heat and in minus 30 degrees below zero. Now I had somebody to protect me – my husband, who always was there for me in adversity. Once I didn’t go to work, when the frost was severe and stayed at home. Jewish policemen found me and made me go to work in severest frost. After that my aunt literally made me go to one of my acquaintances, married to a Jew, who was a foreman of a special team, which served for Estonian and Fascist big-wheels. That lady was a nurse and she worked at the first-aid post. Before the war she was friends with my mother and even came to see my parents in Skaudville. The nurse recognized me and made arrangements for me to work in the city – I cooked food for the team, where her husband was working. I managed to get some food for me and my husband.

Once, in the apartment of some Fascist boss, where that team was repairing something, his wife let me use the telephone. I called my Lithuanian friend. She came over there and we had a long talk. Then she brought me food a couple of times. I was lucky in many things. People treated me very well. Even policemen and Fascists sympathized with me. For instance, we were sent to gather apples in one of the orchards. The German guard whispered to me in German: ‘Take apples with you, I will be scolding you in front of everybody, but you pay no attention to that.’

Once I met a Lithuanian soldier, who used to play in a brass band in our yard in Siauliai. Though he saw me when I was a girl, he recognized me. He also gave me a large chunk of bread and sausage and saw me off to the gate of the ghetto. Once I was in the group of the youth sent to harvest potatoes in the village. I was missing my husband. In about three days he came and brought me a couple of candies. My husband made it possible for me to leave work there and come back to the city. People from the ghetto were often taken to work to other cities. Some of them were even taken to Estonia. We were afraid of being included in those teams. People said that Estonian policemen were very cruel and working conditions were very harsh. People died there very quickly. At any rate, I don’t know any single survivor from those who worked in Estonia. Once I was included in that team and policemen came to get me. I was given some time to pack and they took me. I thought I wouldn’t see Ilia ever again. Shortly after that he came. With the help of his friends Ilia made arrangements for me to be released – as if I was sick and couldn’t work in Estonia. Those friends of my husband were from the underground.

By the end of 1942 my husband had become an active member of an underground organization, acting in the Kaunas ghetto. It was a strong and large organization, which had infiltrated all the authorities of the ghetto, including the Jewish police. They warned people of the coming actions so that as many Jews as possible could be saved. My husband also was on assignments of the underground. He got weapons and brought them into the ghetto. I don’t know whether the people from the underground were involved in the organization of the insurrection in our ghetto, but they had been provided with weapons by 1944.

One of the tasks of the underground was to save young people and children. The latter were stealthily taken from the ghetto to an orphanage, to Estonians, who presented them as their own children. It was so to say a global task, viz. not to let the fascists fulfill Hitler’s order on the ‘Final Solution of the Jewish question’ 17 that is the extermination of Jews as a people. It was obvious that the underground members decided not to fight within the ghetto as it led to irrevocable losses and deaths of innocent ghetto dwellers, who had nothing to do with the underground organization. It was decided to arrange escapes for as many people from the ghetto as possible.

In November 1943 my husband Ilia Olkin left the ghetto in a group of five people. The group had connections with Lithuanians. They were met and taken to Belarusian forests. My husband said good-bye to me and both of us hoped to see each other again. My husband asked his friends from the underground to make arrangements for me to leave the ghetto at the earliest convenience and take me to the place where I could wait for the Soviet Army. In a while the intermediary gave me a letter from Ilia. That man took people to Belarus. He came back for another group.

Life was hard for me when my husband left, but I thought that he broke through the ghetto, would help me leave it so that we would meet in a partisan squad and never part again. The spring of 1944 was very hard. There were constant actions in ghetto. People were taken to executions more often. In April the Fascists carried out the most horrible actions against children. Within an hour they walked from house to house and took all the ghetto children, including infants. Everybody, who couldn’t find a shelter, perished.

The underground organization also reinforced its activity. Now people were taken out of the ghetto en masse. Security guards by the gate were bribed and many people were taken via the gate. The whole network was organized. Women were taken from the ghetto in a truck as if for work and they weren’t coming back. Of course, all that cost a lot of money as both Germans and policemen were to be bribed. Unfortunately, I should admit that Jewish policemen made a fortune on the sorrow of their fellow Jews. It was important to take people from the ghetto, but it wasn’t the most important thing. People, having left the ghetto, were to be provided with shelter. Underground members also took care of that.

I was haunted by premonitions. No news was coming from Ilia. Besides, his friends from the underground paid more and more attention to me. At that time they knew that my husband had perished. I also felt it, but nobody told me about that. The underground members told me about the place on the free side, where I could go into hiding. They acted fast. They met a Lithuanian woman. Her last name was Kutorgene. She was a rather elderly lady, a doctor –ophthalmologist, who had her own practice in Kaunas. Kutorgene had already saved one Jewish girl. One of her patients was a Catholic priest, who helped her save people. That priest made arrangements in the convent to hide a Jewish lady. The only condition was for that woman to speak very good Lithuanian and not to look typically Jewish. I met all those requirements and underground members suggested that I should leave the ghetto. I met Kutorgene at a house, where I was supposed to come after my escape. At that time I wasn’t in the ghetto and I could come into the city while performing work in the service team.

Before leaving the ghetto I went to see my relatives –Uncle Abram and his wife, Aunt Liza and the rest. I said nothing of my intentions as it was dangerous. It was problematic to leave the ghetto at that time: police guards had been replaced by SS-security who couldn’t be bribed. I couldn’t leave with the team as the number of those who entered the ghetto had to be the same as those who left, otherwise the whole team would be shot. My escape was prepared beforehand. First of all, I was well dressed. The cobbler made me a good pair of shoes. I looked like a true Lithuanian, not like a harrassed ghetto woman. There were secret places in the fence made by the underground members, where barbed wire was cut and connected by pegs. It was done in an area far from the main gate, out of sight of the guards. That manhole wasn’t checked by the Fascists who thought that it was impossible to get through there as it was coming onto a street so overgrown with weeds that it was difficult to walk through. I buried my documents in a convenient place. One of the underground members, my husband’s friend, helped me walk through, he distracted the SS-guard, took him aside, while I parted the wire and crept though the hole and dashed to the impassable street. This happened one evening in late May 1944.

I saw the crew on their way back from work to the ghetto, and I hid for nobody to recognize me and call me. I managed to cross the bridge and came to the center of the city, where Kutorgene lived, near the Opera and Ballet theater. I went to her office, where the patients were received, and made an appointment. When it was my turn, I entered the office. Kutorgene recognized me immediately and took me to the living-room. Soon her consulting hours were over and she came to me. Kutorgene told me to sit at the table and we had lunch. Her son came and she introduced me to him, saying openly that I was a Jew from the ghetto. I understood that her son was aware of her anti-Fascist activity and thought that I shouldn’t be afraid of him. But Kutorgene didn’t tell her relative, who was seeing me off to the station and buying me the train ticket to the convent, that I was a Jew. She just told him to see me off, saying that I made up my mind to become a nun. On my way, the man was talking me into not going to the convent and staying in this world as I was so young! I kept silent.

I saw a lady from my lyceum at the train station and tried to hide away, for her not to recognize me. I asked the man to buy me a train ticket. I didn’t want to attract attention by the booking office. I wasn’t frightened, on the contrary, for the first time in so many years I felt free. However, I was to be very disciplined and attentive. When I tried to get on the train, a Lithuanian guy started chatting me up. I was flirting with him, having decided that if I was of a somewhat suspicious appearance, he was beyond suspicion and it would be easier for me. I talked the guy into going in the freight car, not in the passenger car. There were fewer people and it was dark in the freight car, so it would be difficult to distinguish me. We had been talking for a long time and I fell asleep. Suddenly I woke up from words spoken in Yiddish. I was speaking Yiddish in my dream. The guy was looking at me agape and I burst into laughter and said that I was learning German and spoke it in my dream.

I got off in the town of Dotnuva [about 100 km from Vilnius], the place in the closest vicinity to the convent of Saint Katrina, where I was expected. I calmly went up to the policeman at the station and asked where I could call the convent from. He took me to the director of the train station and I called the convent. I was told to wait at the station and they sent a cart to pick me up. When it arrived, it turned out that they were supposed to go to another place before the convent. I was afraid to go with them as in that place the crew from the ghetto was working and I didn’t want to be recognized. I went to the convent on foot.

They were waiting for me at the convent. The abbess, Mother Prontishke, was very affable with me and invited me to sit at the table at once. There were well-forgotten products on the table – I had even forgotten of their existence – bananas, oranges, apples, fried chicken and fish. The abbess and the priest were sitting at the table. They started asking me about life in the ghetto. I felt really drowsy as a result of fatigue and tension since my escape from the ghetto. I begged them pardon and said that I was really sleepy. The abbess took me to a room with three bunks. She tucked me into bed and said that I shouldn’t get up in the morning when the girls would be going to pray as I should rest as much as I wanted.

In the evening, when the girls came back from work, I was asleep. Early in the morning, the bell rang calling for prayer. One of the girls came up to me, kissed me on the cheek and calmly invited me for a prayer. I explained to her that the abbess allowed me not to pray today. After that nobody addressed the issue of praying. The abbess gathered all novices and told them that I was a Jew and would be in hiding there. The food would be brought into my cell and she strictly forbade everybody to say anything about me, even to their closest relatives.

I stayed in the convent until the arrival of the Soviet troops. I rarely left my cell. I started knitting to kill time. The girls brought me threads. Of course, it was sad to stay in almost all the time and I took walks in the convent garden. It was the season when the berries ripened: currant, strawberries. I enjoyed eating them straight from the bushes. Sometimes I went to the cathedral by the convent. I sat in the last pew so that the parishioners wouldn’t see me – people from local villages came to the cathedral – and I listened to the Catholic mass.

In a while another Jewish woman was brought to the convent. I don’t remember her name, though I would like to find her now. Her parents and little brother were shot. That woman was baptized in the convent and took the veil. I always wondered at how desperately she was praying. It wasn’t clear to me how one could become an apostate. Nobody compelled me to pray in the convent; moreover nobody forced baptism on me.

May and June had passed. It was early July 1944. The German army was retreating. A Fascist unit was positioned in the convent garden. I had been staying in my cell for several days. When the Soviet troops were approaching, the abbess had the girls go home as she feared repressions from Bolsheviks. I also was to go. I was dressed like a true Lithuanian peasant. Looking at me, the girls were crying and laughing at the same time, so unusual I looked. They came to love me during that period of time. We were given a cow. Thus, the three of us – a girl, me and a cow – went to her farmstead. The girl told her parents and neighbors that I was a Lithuanian teacher from Vilnius, escaping the Bolsheviks. However, one of her neighbors told her mother that I was most likely a Jew, but luckily he didn’t betray me.

When the Fascists came to the farmstead, they were sympathetic when they heard my story and ranted about the Bolsheviks. One of them knocked on my window and offered me to run away with them, when the Soviet troops were approaching. I replied that I couldn’t leave with the army and would have to go my own way. In the morning the Soviet army entered the farmstead. I was the first to come up to them. I was overwhelmed with joy. I couldn’t believe myself: three years in the ghetto were behind me. I told the soldiers that I was a Jew from Kaunas and they broke joyful news to me: Kaunas had already been liberated. On that very day I went back to the convent. I wanted to say good-bye to the girls and the abbess, who saved me. I stayed there for a couple of days, and decided to go back home. I was looking forward to seeing Kaunas, finding out something about my parents and husband.

It was the end of August 1944. The abbess kissed me and gave me some food and money for the road. I walked through the forest to the train station. On the way some cart caught up with me. I was lucky again – the cart was driven by my school teacher from Siauliai. He recognized me and took my things on the cart. I couldn’t get on it as it was full. Thus, we reached the train. There were no tickets. Only militaries could get on the train. Then some military said that I was his wife and I was let on the train. Thus, I got to Kaunas. There at once I found the underground members, who helped me leave the ghetto.

During the liquidation of the ghetto all my relatives perished: my father’s siblings. The members of the underground organization told me that my husband, Ilia Olkin, perished in spring 1944. He died by accident. A partisan squad, where he served, was dislocated to a Belarusian village. At night, on the way back from the task, my husband said the password. The sentinel shot Ilia either because he didn’t hear the password, or because it had been changed. He was severely wounded and passed away by the morning… My premonition was true. I became a widow without a chance of knowing the happiness of married life in peaceful times. My mood was terrible and I thought that I wouldn’t get married again and keep the last name of Olkin.

I decided to look for my kin. Those, who were seeking their relatives, sent letters to the municipal council of Kaunas. There I found a letter written by my father. He was hoping to find his brothers and thought that they would know something about me. My loved ones had no idea that I happened to be in Kaunas at the beginning of the war. They were looking for me in Siauliai and Vilnius, sending inquiries there. My name was Olkina at that time, but they were looking for a Liza Abramson.

My parents and brother were in evacuation in Ural, in the settlement of Kosa, Komi-Permyak oblast [1500 km from Moscow]. In 1944 they came to Kharkov, where after the evacuation Grandmother Anna was living. I sent a letter to their Kharkov address – in Russian but with Lithuanian letters as I didn’t know the Russian alphabet. Having received my letter, Father was crying and laughing at the same time, walking to and fro in the room. He called Mother from work. She was working in a pharmacy. My parents wrote me a letter, to the address of the municipal council. There was no place for me to live in Kaunas and I stayed with my acquaintances. I found out that all of them were alive and healthy.

My brother Abram had married his friend from Vilnius during the war and now he was living there. My brother’s wife was the daughter of the most famous tailor in Vilnius. My brother was seeing her before the war, but it happened so that they met again and got married in evacuation. My brother was drafted into the army and served in the 16th Lithuanian division 18. Since he was an excellent accordion player, he joined the military orchestra right away. Right after the liberation of Vilnius a Lithuanian band was founded, where my brother played the grand piano. His wife was a singer and she worked with him. I went to see my brother in Vilnius. At that time they lived on the premises of the philharmonic society. At first, I stayed with them. We slept on the floor.

I started looking for a job. My sister-in-law’s cousin Hana was a famous underground member and partisan, a member of the Communist Party. She recommended me to the secret department at the Council of Ministers of the Lithuanian SSR. The job was very serious. We received top-secret letters and orders and distributed them to different ministries and authorities. I wanted to go on with my education, at Vilnius University, but I didn’t manage to study as I was very busy at work. Being employed at a governmental institution I got good product cards – the best products available, even delicacies – while by common food cards 19 only insufficient products were given. In the postwar period life was hard and people starved. Soon I was given an apartment – a wonderful two-room apartment in the heart of Vilnius. I moved there with my brother and his wife. I sent an invitation to my parents as they wouldn’t have been able to return to Vilnius without that document. Soon they came and moved into my apartment. Shortly after that, Father found a job in the office of subsistence production.

I kept friendly relations with Abbess Prontishke at first, after the war. The convent was threatened with closure due to the politics of the Soviet regime, in accordance with the struggle against religion 20. As per request of the abbess I arranged for her an appointment with the plenipotentiary of the Council of Ministers for Religion. She came to Vilnius, stopped by at our place and met with that person. He treated the abbess with respect, but nothing could be changed. Soon the convent was broken up and closed down. The abbess left for her motherland and I never saw her again. I also saw Kutorgene. She worked as a doctor for a couple of years in Kaunas. She died in the mid-1950s.

Soon after my parents arrived I went to my hometown, Siauliai, in order to get some documents in the archive as I didn’t have a birth certificate and school certificate. The first person I saw when getting off the bus was Eduardas Kudritskas – my friend from childhood and my calf love. He was happy to see me alive. We had a long talk. Eduardas saw me off and came to Vilnius a couple of times hoping that I would be with him. But it turned out to be quite different.

There was a Soviet military unit not far from our house. My brother met three officers and invited them to come over to us. One of them, Colonel Vladimir Lukinskiy, a tall handsome man started courting me. I didn’t mind his courtship as I liked Vladimir very much. It wasn’t that I forgot about my husband whom I loved, just being young… Vladimir Lukinskiy was much younger than me. He was Russian, born in Leningrad in 1924. Vladimir came from a rich family. His mother Katerina was from a noble family. She raised her son in a wonderful way. Vladimir was well-read, educated, loved opera and classical music. I found him very interesting. While we were mere friends, my parents treated him very well. Gradually our relationship changed. We fell in love with each other and Vladimir proposed to me. All of a sudden Father opposed to that. He was flatly against my marriage to a non-Jew. He remembered Eduardas and was sorry for not letting me marry him, and again I was dating a non-Jew.

Once in winter 1946 I invited Vladimir for lunch. He brought canned products and firewood. In that period of time it was hard to find supplies. When Father found out that Vladimir made all those presents, he put everything in the garbage can. I told my fiancé the way it was. He reacted calmly to that and invited me to a restaurant. Here he ordered all kinds of delicacies: caviar and ham. Since that time Father started turning out Vladimir, when he came over. Father went on a trip and I decided to have a talk with Mother, woman to woman, and told her about our love. Mother said that I would marry him only ‘over her dead body.’ Then I took my nightie and left home without anything. In spite of the fact that it was my apartment I left everything there, even my food cards, for my mother.

Vladimir and I rented an apartment and moved in there. Once in the evening after work we were passing by my house. Mother was on the threshold and said, ‘Dinner is ready.’ Thus, Mother accepted Vladimir. When Father came back from the trip, Mother told him that I was living with Vladimir. Then Father collected all the presents he had brought me, Mother took linen, table cloth, dishes and they came to see us. Since that time Father and Vladimir became as thick as thieves. My husband never remembered how my parent gave him a hard time at first.

I insisted that Vladimir should be demobilized from the army. I didn’t want to be an officer’s wife and spend all my life on the road. He was demobilized and found a job. Our marriage remained unregistered for a while. The red-tape Soviet laws demanded either the documents on the divorce with Olkin or his death certificate. I didn’t even have the marriage certificate, issued by the Judenrat, as I buried all the documents when leaving the ghetto. I had to walk from one office of a dignitary to another and finally we were permitted to get our marriage registered. It happened in 1946.

In 1948 I gave birth to a son and named him Alexander. For a while my son and I were living with my parents. When our son turned seven months my mother-in-law – my father-in-law had passed away by then – exchanged her apartment in Leningrad for an apartment in Vilnius and we moved in with her. Our apartment was in the heart of Vilnius, consisting of two rooms and a kitchen. One room was taken by my mother-in-law and the other by my husband, son and me. My mother-in-law was a wonderful, clever and kind woman. She accepted me and loved me like her own daughter, helping me in everything, especially in raising our son.

My husband was a member of the Communist Party. I didn’t join the Party as I had been in the occupation. At that time it was disgraceful. After my son was born, I kept working at the secret department for a while and in the early 1950s, when state anti-Semitism was rampant, I was told to quit my job because I wasn’t a Communist. I found a job as an HR inspector in the Lithuanian Consumers’ Council. At that time my husband was called to the military enlistment office and drafted into the army for the second time. He was to be sent to the border with China, but he was lucky. He met his friend from the army in the military enlistment office and he offered my husband to go to Leningrad to teach at some courses for officers.

My husband left for Leningrad and I stayed with my son. It was January 1953, when the Doctors’ Plot 21 was in full swing and doctors-poisoners were the most topical issues in the papers and radio. There was tittle-tattle among Vilnius Jews that there was an order to deport all Jews to Birobidjan 22. I called my husband in Leningrad and told him about these rumors and added that if I got deported, I would leave my son with my mother-in-law. It was a very hard time. I was calm only after Stalin’s death. My husband insisted on my moving to Leningrad. We decided to leave our son with my mother-in-law and I moved to my husband. We lived in Leningrad for three and a half years.

Ekaterina Nikolaevna did well raising my son. My parents were also helping. Every day my mother came over to spend time with her grandson, but Alexander was missing his parents. I insisted that my husband should be demobilized as we had to come back to Vilnius and raise our son. In 1957 Vladimir was demobilized for the second time and we came back home. I found a job in the book-keeping department at a tinned food plant. I was promoted to chief accountant and worked there until my retirement. I left work in 1987.

My husband and I had a wonderful life together. In 1973 we got a nice three-room apartment, where I am currently living. My mother-in-law lived with us. She was a second mother to me. Ekaterina Nikolaevna died in 1976. As for the material side, we lived pretty modestly, like most people during the Soviet regime. We owned neither a car nor a dacha. But we often attended concerts, theater performances, read a lot, went on vacation to Palanga and the Crimea. We liked the village of Rybachiy in the Crimea, not far from Alushta. We made friends with a local family and went there on vacation every year.

Neither Jewish nor Christian Orthodox holidays were celebrated by us as Vladimir was a member of the Party. I often cooked Jewish dishes and laid a festive table on Pesach. While my parents were alive we went to see them on Jewish holidays. It was a family reunion: I with my husband and son, and my brother and his wife; they didn’t have children.

My father lived for 82 years and died in 1969. My mother invited an old Jew from the synagogue and he read a prayer for my dad. I couldn’t have my father buried in accordance with the Jewish tradition – without a coffin. I couldn’t picture that my father would be in the earth. Father’s funeral was secular. Мy mother died in 1986, she was buried next to my father at the Jewish cemetery of Vilnius.

My brother’s family did well. He worked at the Lithuanian symphonic orchestra and his wife was a singer at the Opera and radio. My brother was afflicted with cancer and died at the age of sixty. His wife left for Israel. She never remarried.

My son was a wonderful boy. He was an excellent student at school and he obeyed his parents. I can say that I didn’t have any problems with him as a teenager. When he came of age and was to receive his passport, the issue of nationality came up 23. Vladimir said that it was up to me. I had a talk with my son and told him that he had always been a Jew, but he should put the Russian nationality in his passport, not to feel any discrimination in his education and career. My son did as I told him. His nationality is Russian, but he is a Jew in his heart.

My son served in the army, entered the university and finished the Economics Department. During the Soviet regime he was in charge of the bureau of heating appliances of the largest plant. That plant went bankrupt and Alexander doesn’t have a permanent job. He is involved in small business. My son divorced his first wife, who bore him a daughter, Yulia. She finished the Philology Faculty. She is fluent in English. Yulia is a business lady. She has a daughter, my great-granddaughter Anastasia. My son married for the second time, a Russian woman named Natalia. The most important woman for my son is me, his mother. He loves me dearly and comes to see me every day. My son buys me all kinds of scrumptious things I like and helps me about the house. My son started taking special care of me after my husband’s death in 1998.

Since that time I am on my own. Jewish life was revived in the period when Lithuania gained its independence in 1991 24. I think it was the only positive factor of perestroika 25 and the breakup of the USSR [1991]. I don’t like the altercations in the Lithuanian parliament. It seems to me that every member of the government is thinking only of himself. Life in Lithuania became bleak, and there is no sense in leaving for Russia as my motherland is here, and nobody is waiting for me in a different place.

My husband, who had always been friends with Jews, suggested leaving for Israel in the 1970s. I didn’t want to as, unfortunately, during the occupation I saw different Jews – some of them were starving, others were making money on that. That is why I don’t want to live in a purely Jewish environment, though I have been to Israel and liked it a lot.

As a former ghetto prisoner, I receive a pension from Germany and I have a pretty comfortable life. I can even help out my son financially. Now I am a member of the Jewish community of Lithuania. Every week I come to the department of prisoners of ghettoes and concentration camps tour community and perform different assignments. I celebrate Jewish holidays with my friends. This way I revived my Jewish life. I don’t feel lonely.