Harry Fink

Carlsbad

Czech Republic

Interviewer: Barbora Pokreis

Date of interview: August 2005

Mr. Harry Fink was born in Prague into a widely branched, financially secure family. Unfortunately, except for him, none of his relatives survived World War II. After the war he grew up in youth homes. Despite the tough hand life has dealt him, he has preserved a sense of humor which is typical of him, which is also preserved and evident in his testimony. He currently lives with his wife in a cozily furnished apartment in Carlsbad.

My family background

Growing up

During the war

Auschwitz

Liberation

Post-war

Married life

My children

Political events

Glossary

My ancestors on my father's side [Ludvik Fink] come from Southern Bohemia, in and around Bernatice, which is near Pisek. The name Fink means Finch in English. I didn't know my great-grandparents, only my grandparents.

My grandpa on my father's side was named Hynek Fink. He died in the year 1933, at that time he was definitely over 80 years old. I don't remember my grandfather much; I was very small when he died. My grandmother was named Terezia [Finkova, nee Mautnerova] and died in Terezin 1, probably in 1943. She wasn't as old, she might have been about 75. I don't remember my grandfather; he died when I was two. I only remember that always when we went to visit, I would bring him a box of pipe tobacco. That's all I know about my grandpa. My grandma was a very kind lady. Her I remember very well. She was a proper grandmother. She treated her grandchildren well; she never favored one over the other. My aunt [Maria Vojtova, nee Finkova], with whom she lived, had one daughter [Viera] and when later Milan [son of Jaroslav Fink] was born, he was a cousin, we were all hers.

In his youth my grandfather had been a farmer, so it's obvious how they made a living. They lived in Bernatice, and later, when he retired, they moved to Prague. Three of his sons and one daughter were already living in Prague, so they moved. They lived in the neighborhood of Nusle in an apartment building. From the whole apartment I only remember the front hall, because that's where all of my grandfather's pipes used to hang. When Grandpa died, my grandmother moved in with her youngest daughter [Maria Vojtova]. While my grandfather was alive, we used to go visit them about once a month. After he died we didn't go visit my grandmother as often, because they lived further away, in the Strasnice area of Prague, and those were the ends of the earth. We used to go there quite a bit less often.

I don't remember my grandfather going to the synagogue, and in this regard, I don't know anything at all about my grandmother, because the daughter that she lived with was in a mixed marriage. My uncle [Frantisek Vojta] was a Christian. Grandma was happy there and that's what was important. My grandfather wore a hat, he had a beard too, but not that Orthodox kind, a normal one like old men usually wore back then, seventy years ago.

My grandparents on my mother's side were the Scharpners. Leopold Scharpner was from Hermanov Mestec [region of Pardubice, Chrudim county]. Grandpa died in the year 1937 and by then he was quite a bit over 80. My grandmother was named Jenny Scharpnerova, nee Fischlova, and died on a transport from Terezin to Auschwitz. It could have been in 1943, she could have been over 70 as well.

I used to stay with my grandparents during summer holidays, because they lived in Hermanov Mestec and that's only a hundred kilometers from Prague. I knew my grandfather as already a very old man. Grandpa was a shoemaker. My grandma was of course a housewife. They probably lived well, because they had a multi-story house built on the main square. They lived on the first floor, where they had four rooms, and the rooms downstairs were rented out. Plus in the back there was a general store, so they must have lived well.

Hermanov Mestec was a small town of several thousand. There were relatively a lot of Jews living there, but I don't know how many. The last time I was there was in 1937 or 1938, and at that time I was seven years old. So I don't remember much. My grandparents had non-Jewish neighbors. There were no Jews in their street, only a bit further on. There were the Schultzes, Neumanns, Pokornys, but they weren't immediate neighbors.

I also remember one thing that happened back then. There was a sewer running through town and some rats ran into it. Of course I flew in after them, into that stinky sewer. When I returned home, I got bawled out for it. In my defense I said, 'But there were kittens drowning in there!' A child from Prague can't know this... Otherwise I got into the same kinds of trouble as all children. Once we went stealing pears, another time plums, that's how we amused ourselves, like it normally is in small towns and villages.

My grandfather went to the synagogue, that I know, but he was by no means Orthodox [see Orthodox communities] 2. He'd go to the synagogue and then to the pub. During Sabbath he probably didn't go to the pub, I don't know. They definitely didn't observe Sabbath, maybe only as this little trifle, but not the real Sabbath as it's observed. I absolutely for sure know that they didn't keep kosher, neither did my parents nor my mother's parents. They ate pork at home, as well as meat mixed with dairy products.

My father was named Ludvik Fink. He was born in Bernatice in the year 1891. He studied some trade in the textile industry. My mother was named Marketa Finkova, nee Scharpnerova. She was born in Hermanov Mestec in the year 1898. I don't know if she studied anything, she was only ever a housewife. She finished her compulsory schooling, which was I don't know how long during the time of Austria [Austro-Hungarian Monarchy]. Both spoke German and of course Czech, and my father also spoke Serbian. Among themselves they spoke only Czech. I don't know how they met, they never talked to me about it and there wasn't even time for it, I was still small.

We lived in Prague, on Jindrisska Street. Our apartment was in a former palace. It was a huge apartment building with three stairwells and dozens and dozens of rooms. The ceilings were 4.8 meters high. The smallest room was the bedroom, which measured about 68 square meters, about the same as my current apartment. Originally we lived in the third wing. We had four large rooms, a toilet, pantry and kitchen. There was one more small room, which was the children's room, and also a bathroom. The building belonged to the National Bank and it decided to use our apartment for an archive, so they moved us into the first wing, the first staircase on Jindrisska Street. But from what I remember for those four years the apartment stayed unlocked, so that I rode my bike around in those huge rooms and organized races.

The apartment was very nicely appointed. The furniture was from the Exner company in Kutna Hora, my current furniture is also from that company, but by then it was already a state company. I was an only child, I had my own room, which was that little room. It was 3 x 5 meters. Of course at first I slept with my parents in their bedroom and then, when I was older, I slept in my own room. I had a large closet, a child's bed, a couch and table with chairs, because we used to also eat there. It was the only usable room, because as large and beautiful the rest was, it wasn't livable. Why? While in the summer it was perfect, during the biggest heat waves it was comfortable, in the winter it was cold, and the rooms couldn't be heated enough. In the evening we'd undress, wash in the back in the bathroom behind the children's room, put our hands on our breast and run to the bedroom. We'd hide our heads under the duvet and only after a while stuck them back out, because those rooms weren't heatable. When guests were to arrive, the stove had to be on for two days beforehand. The Dutch, or tile stove reached all the way to the ceiling. It had to be on so that you could stand it in there and so you could sit in the dining room.

My father had a company, he manufactured ties and sold tie textiles. He needed some sort of suitable space for his activities, so he rented that apartment of ours. The largest room of all served as a store. My father, like a proper businessman, dressed elegantly. He wore pants, a suit jacket and a tie. I think that my mother also dressed very well. She didn't wear pants yet, just long skirts and with them various kinds of blouses. My parents had their clothing made at 'U Papeze na Perstejne,' in those days that was a renowned tailoring company. My father had his ties made privately by seamstresses. He cut the cloth himself, prepared it, and then the seamstresses took it away. A regular customer of ours was Josef Laufer, a broadcast journalist and famous reporter. [Laufer, Josef (1891-1966): Czech journalist, founder of sports journalism and radio sports broadcasts. He commented the first live soccer game broadcasts in the year 1926 and hockey broadcast, in 1931, in Czechoslovakia.] He used to come to us relatively often. I remember only him, otherwise I didn't hang around the store much. My father was glad when I came there, but would say, 'OK, don't hold me up, run off again!'

My parents were on the stricter side when it came to me, there was no shortage of the occasional slap here and there. Mainly from my father, my mother too, but then it really had to be for good reason. She went at it cleverly, she'd complain about me to my father, and my father would take care of me tout suite. I think that my father was the stricter one. He was terribly touchy regarding school. I remember when I was small, and at school we had religion class [Judaism], and once the class was cancelled and I came home an hour early. And my father didn't want to believe me, so he ran over to my school and went to ask whether I wasn't making it up. Well, I really wasn't making it up. But that wasn't of any use to me, because that day I had done something, I don't even know what any more, and I got a good hiding.

A servant by the name of Bozenka helped my mother with the household. I had a nanny, Pavla, but I don't remember her surname. We always just called her 'young lady.' This young lady worked for us until I started school, because I didn't attend nursery school. She took care of me and took me on walks and to the park. Bozenka had to work hard, because our apartment was horrible. Only those four rooms in the front had a total of about 300 square meters, and then there were all sorts of other things, hallways and foyers. And to clean all that...My mother only cooked and went shopping, except for vegetables, that was my father's thing. I've got to say, that my mother cooked very well. My favorite food was apricot dumplings with cottage cheese.

We had a lot of books at home, but only general ones, not on a Jewish theme. The only thing that I've got left after my mother are her four books from Machar [Machar, Josef Svatopluk (1864-1942): Czech poet, writer, journalist and publicist]. Evidently he was her favorite author. She always signed her books. Otherwise we had a lot of books at home. As a child I very much liked to read. I very much liked the book Kaja Marik [by Wagnerova-Cerna] 3. It was about this boy who was the son of a forest ranger. From a religious standpoint it was very nicely written, because it was written by a Catholic parson. [Editor's note: the book's author, Marie Wagnerova-Cerna was a landlady of a parsonage and wrote under the male pseudonym of Felix Haj. Perhaps this is why the interviewee assumed that the author was a Catholic parson.] He wrote about seven or eight books about Kaja Marik. It was very nice reading.

My father used to regularly go play cards at coffee shops. Always, when he had the time, he went. He used to take me with him. I kibitzed constantly. Most often he would go to a place on Wenceslaus Square. In the bathroom there was a gambling machine. My father smoked 'Virginias,' those long, thin cigarettes with a straw inside. When you bent that straw and stuck it into the coin slot and hit the prize hole - you couldn't hit it too hard - the straw fell into the prize hole and some crowns fell out. I learned this from my father. I always came to him: 'Dad, give me a crown!' He'd give me a crown and I'd play the machines. I always managed to make some money, also with the help of that straw. Of course, as luck would have it, my father went to the bathroom and saw me standing on a wastebasket, because it was high and I was small. I immediately got a couple of cuffs and I yelled: 'But you're the one that taught it to me!' That's about how I used to pass the time when I was with him.

I used to go on vacations with my parents. Once, when I was in the first grade, my mother and I went during the winter holidays to the Tatras [The High Tatras, the largest and highest mountain range in Slovakia]. Concretely, we were in Tatranska Lomnica, skiing. My mother also skied, and skied very well. My father didn't have time for such things. Otherwise my mother and I used to go visit my grandmother in Mestec [Hermanov Mestec]. We also used to go a little ways outside of Prague to Radejovice. We had a place rented there, and my father would come in the evening, because it was a suburb of Prague and today it's part of the city. Back then it was still a village in the forest. So we used to go on vacations like this as well. We also drove around the region surrounding Prague, to Karlstein, to St. John's Currents to swim. While we still could, before they took our car [see Anti-Jewish laws in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia] 4 we went on trips and then, when we couldn't have the car any more, we stopped.

We kept in regular touch with our relatives. Uncle Jara [Jaroslav Fink] lived on the same street as we did, Jindrisska. The Brichta family [Karla Brichtova, nee Finkova] lived on Londynska Street, and that's all in the center of Prague. We saw them often, except for Uncle Alfred [Fink], who only came to Prague once in a while, because he lived in Teplice. Mother's brother, Uncle Ruda [Rudolf Scharpner] lived in Prague and Aunt Zelma [Zelma Glasserova, nee Scharpnerova] in Pilsen. By the way, there was one son [Jiri Glasser] born of that marriage, who lives in England. Aunt Anca [Anna Pachnerova, nee Scharpnerova] lived in Brtnice [Jihlava county].

My father was one of seven children. The oldest was Aunt Eliska, then Uncle Alfred, Aunt Mana [Maria], Aunt Marta and Aunt Karla. Eliska's married name was Spirkova, I never met her husband, he had already been long dead and Aunt Eliska was awfully old as well. She died in a concentration camp in the 1940s. She had one son, but I don't remember his name any more, I never met him either, because he was so old that he fell in World War I.

Uncle Alfred Fink, like my father, was in the textile business. He died sometime during a transport in the 1940s. I don't remember his wife at all. They had two children, Hanka [Hana] and Jirka [Jiri]. Hanka died during the war, and Jirka survived it. During the war Jirka was in Denmark.

Uncle Jaroslav Fink died in Terezin in 1944. He had one son, who was named Milan. Jaroslav had a store, where he sold cutlery - knives, forks and so on. His wife was named Marta. Their son Milan left in 1947 for Palestine, but he's been dead about five or six years now.

Aunt Marta Finkova never married, she stayed an old maid, she was a bit off her rocker. She never worked, my grandparents supported her. Aunt Marta died in Terezin. Aunt Maria Vojtova married a Christian, Franta [Frantisek] Vojta. They had two children, Viera and Franta. For a long time Aunt Maria worked as a clerk at Ferona, that was a company that exported steel and things like that. [Editor's note: in the year 1829, in Prague, L.G. Bondy founded a wholesale hardware business, which in 1919 became a corporation named FERRA a.s. Through various periods of transformation and mergers with other companies, the Ferrona company came into being in 1972.] During the war both my aunt and Viera were at home the whole time, and towards the end of the war, they stuck my uncle, as a Christian husband of a Jewess, into Svatoborice [district of Southern Bohemia, Hodonin county]. They were allowed to go home about once every fourteen days. Aunt Karla married Jirka Brichta. Uncle Brichta was some sort of PhD, probably a Doctor of Law. He came from someplace around Trencin.

My mother had three siblings - Aunt Zelma, Aunt Anca [Anna] and Uncle Ruda [Rudolf]. Aunt Zelma died sometime in 1943 and now I don't know whether in Terezin or Auschwitz. My aunt's last name was Glasserova and she lived in Pilsen. They had two children, Jirka [Jiri] and Hanka. Aunt Anca Pachnerova died during the war. She has two children, Vilek [Viliam, Vili] and Jirka. Jirka died during the war during a transport. And Vili lives to this day in America, he's about 93 now [2005]. Uncle Ruda was probably a bank clerk. He and his wife died during the war, they were childless.

Prague had around 800,000 inhabitants, of those 30 or 40,000 could have been Jews. I don't know how many religious communities there were there, I was too small at the time for that. There were lots of synagogues, they've been preserved to this day. I remember the Old New, the Maisel, the Spanish, and I don't know what ours was called [the Jerusalem Synagogue, earlier the Jubilee Synagogue]. It stood on Jeruzalemska Street. I don't remember the name of the rabbi there. I only remember one thing connected with Judaism. I used to go school at the Teachers' Institute on Panska Street. During Simchat Torah, I dragged half my class to our synagogue, though the boys were all Christians, right? In the synagogue people were praying, and then children walked down the middle and got cat's tongues [sweets]. We went out, walked around the synagogue, and in again. We continued like this until the tongues were all gone. Then we thought it better to leave. We managed to gather up two, three boxes of them.

At home, the only thing that was really observed was Passover. We'd always order matzot and my father and I would wrangle over them. My father would break the matzah into pieces and put them into this big pot, from which we would then take them. My father used to attend that synagogue, whether he used to go there regularly, I don't know, because on Saturday the stores were open, so he couldn't go. We also observed Chanukkah and also Christmas. We got gifts only for Christmas. We had a Christmas tree and ate carp, so with us religion wasn't a dominant thing. For Yom Kippur my father went to the synagogue, he was always ill-tempered because he was starving.

There were fairs held in Prague before the holidays. The closest to us was in the Old Town Square, that was a beautiful market and fair. It was spread out all over the square and there were all sorts of stalls, shooting galleries, sweets, merry-go-rounds, and so on. Sweet stuffed buns and Turkish delight... This took place twice a year, on the Old Town Square. Then we used to go, but by this time I was older, to St. Matthew in Dejvice. There were more of those fairs, but these were the main ones.

The shopping at the normal everyday markets, where they used to sell vegetables, was done by my father, because the women that sold there were for the most part from Southern Bohemia, and my father got along very well with them. And he'd talk to them for hours on end. The Southern Bohemians call themselves 'blue-bellies,' because they eat potatoes, at least in those days they ate potatoes. It would be lunchtime and a big bowl of potatoes would come to the table. They say that they have blue bellies because they eat those potatoes. My father used to go to the market on Havelska Street. We also used to go to the Coal Market, that was in the Old Town. There must have also been a market in town where they had fish, but it wasn't a special fish market. Almost all of the markets were on Senovazne Namesti [Hay-weighing Square]. On it there were permanent stalls, and mainly fruit and vegetables were sold there. Undoubtedly they also sold fish there, as well as meat, not so much fresh meat, that didn't exist back then, but smoked meat products.

We lived about 100 meters away from Wenceslaus Square, so that's why I remember well the circus that took place in the year 1938. Understandably, we were there. Otherwise, I remember practically everything that took place. I remember that on 15th March there was a big Wehrmacht parade on Wenceslaus Square. [Editor's note: on 15th March 1939 the occupation of Czech lands by the German armies began.] Despite the cruelty of those times, I have fond memories from those years. For example when they gave us stars [see Yellow star - Jewish star in Protectorate] 5, that must have been in about 1941, and I used to meet normal Christian boys, and they'd call out to me: 'So, sheriff, how's it going?', I simply never met up with any racial hatred, or something like that.

In 1937 I started school, at the Men's Teacher's Institute on Panska Street, where I attended up to the third grade, and then Jewish children weren't allowed to attend state schools any longer. Well, up to now I had thought that it was a matter of course, and only recently did they explain to me, that it wasn't at all a matter of course, that I continued to attend the fourth grade, at a Jewish school. I hadn't at all known that it wasn't like that for everyone, that most of them stopped going to school during the war. Then we went on the transport [1942]. At school I very much liked geography and history. They presented it so beautifully, it was very nice. There might have been about thirty of us in the class [Men's Teacher's Institute], and I was the only Jewish boy.

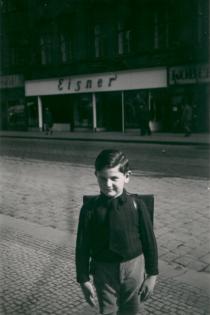

I had a lot of friends. One of the two better ones was Tomik Eisner, they had a store in that building of ours. Mr. Eisner split up that huge courtyard and built a hall there. He had women's clothing there. I still remember their slogan: 'Slim mother, husky daughter, both wear clothes from Eisner.' The Eisners lived on Panska Street, which was just around the corner. I don't remember the name of my second friend. They used to live in Dejvice, and when we wanted to meet up, that was like going to the ends of the earth. We used to go skating on the Vltava and sledding to the Angel Garden, to Hrdlorezy [a part of Prague]. [Editor's note: the Angel Garden was built on property that in 1340 was given by Charles IV to the court apothecary Angelus of Florence, and on which Angelus then created the first botanical garden in Central Europe, named the Angel Garden.] In the summer we used to do all sorts of sports activities, but I didn't excel in any sport.

My father was always complaining about politics, the same way people complain today too. It probably wasn't any better than it is today, but despite this he was a member of the resistance right from the beginning of the war. He joined a cell at Wilson Train Station in Prague. He was friends with one mechanical engineer from the Wilson Station depot, and the connection was made through him, but exactly what and how things took place, that I don't know. I only remember them coming to arrest him. Two Gestapo officers came to our place. I was the first one to see them, because we had a courtyard gallery, and they were on the floor above, looking down, checking things out. I ran after my father: 'Dad, there's a couple of guys in leather coats!' The Gestapo came and when they were taking him away, said: 'Don't worry, your father will be back this evening!' They spoke Czech, for sure they were Sudeteners [Sudeten Germans from the Sudetenland] 6. They arrested him in 1941. He was jailed on Charles Square, up until they deported us to Terezin.

In 1942 my mother and I went on the transport to Terezin. At that time that perverse law regarding the inseparability of families, or how it was called, was in effect, so they let my father out of jail and sent him to Terezin to be with us. Several times we were supposed to leave Terezin on a transport, but my father had some connections from the resistance, so he always managed to get us off the list. Finally he said, enough, it's no use always trying to get us off the list, and so in December of 1943 our whole family went to Auschwitz.

In Terezin my mother didn't work and my father did something, but what exactly, that I don't know. I studied at the town power station in Terezin. In fact they counted that year as part of my years of education. From the time I was small I was interested in electricity, so I arranged it and they took me on as an apprentice electrician. I lived in a 'Jugendheim' [youth home], in L-417. My father lived in the Cultural Hall and there up in the attic they used to build these sheds out of various materials. My father also scrounged up some materials and built himself a shed there. My mother at first lived in Q-218, and when my father built it, she moved in with him.

Our class was a good bunch. I was assigned to a boy who was already studying, he was 17. I used to go everywhere with him, and time flew by. The most unpleasant experience that I had in Terezin took place sometime in the fall of 1943. At that time there was a census and they herded us into the Bohusovice Valley. It was cold and raining hard. We were there from morning until evening. This was perhaps the most unpleasant experience of all from Terezin.

In 1943 they transported us to Auschwitz. We were the first transport to be put in trucks and not go to the gas chambers, it was the so-called December transport. [Editor's note: in December two transports left Terezin for Auschwitz: transport Dr 15.12.1943 and transport Ds 18.12.1943.] When they had stripped, washed, tattooed and dressed us, we then went to the family camp, where they separated us. Men went to the right, women to the left. I lived with my father, but could see my mother as often as I wanted. In Auschwitz we began to recognize what was hunger and misery, and what cold was. My father worked as a 'Stubenältester' [senior room warden] and my mother worked somewhere on the other end in this building where there were these cellophanes and various waste materials. The women were weaving something from it. I suspect that they were making fuses out of it, they'd dip it in something.

At that time we were still all together. We were still holding on. We had a so-called 'Kinderstube' [day nursery] there, where they even taught in some fashion. Fredy Hirsch 7 was in charge of it. It's interesting, that the name of the cook, Libuse, has stuck in my mind. We'd always call out, 'We thank Libuse a lot, for giving us soup from the pot. But if she gave us goose, she'd deserve a kiss!' We children didn't take it so hard, it was a matter of course for us.

In 1944 various selections took place, the whole camp was going into the gas. Then after they sent us off I managed to meet up with my father one more time. Somewhere he had organized [in Auschwitz the words steal - organize were synonymous] some short corduroy pants and somehow got into the men's camp and brought them to me. That was the last time I saw him. My father and mother stayed in the family camp for another day or two, and then went into the gas.

I'm in touch to this day with those boys, with those that are still alive, of course. To this day we study how it was and why they actually took those 97 from the family camp. It was absolutely illogical. One of them always says: 'You had connections, I remember it, during the selection they waited for you. You were the last to come running over.' No one knew why. In the men's camp they moved us into a so-called 'Strafkommando' [penal commando], to Mr. Bednar, a military criminal, who however was terribly fond of us and didn't address us in any other fashion other than Pepiks [Editor's note: Pepik is slang for a Czech]. Sing, Pepiks!

Mr. Bednar was a horrible sadist, he was a multiple murderer. It was the 'Strafblock,' a penal block, and those that went in rarely came out alive, and he deserved it. We did all sorts of things there. We had abnormal standing, we had hair. And to have hair in the concentration camp, that was something! The whole camp loved us. They didn't call us by any other name than Pepiks. I myself worked mainly with the so-called 'Rollwagen.' A Rollwagen was an ordinary hay-wagon, only that instead of horses a couple of boys pulled it along by a rope. We could drive around here and there in the camp. I was in the crematorium many times while it was still in operation, because by the crematorium there was lumber and we used to go get wood there. Which we would then bring to the SS to their 'Stuben,' 'Dienststuben' [offices], they were these buildings that were at the entrance to the camp and they built air-raid shelters there.

I got to know the crematorium while it was in operation. The 13th block was connected with the 11th, and was additionally fenced in, it was a camp within a camp, because living in the 11th was the 'Sonderkommando' [commando responsible for carrying the dead out of the gas chambers and their cremation] from those crematoriums. I got to know them as well. We managed to live relatively decently, thanks to the fact that we drove around with the Rollwagen. We had pails hanging on it, and the SS never checked their contents. When they saw us they always whistled and said 'weiter' [go on!] and we pulled and left.

We would go as far as Canada, that was the part of the camp where they sorted things left after the transports. And when the cook wanted shoes, he'd give us potatoes for someone in Canada. We'd go to Canada, where we'd meet someone and say to him, 'Do you want potatoes? We need shoes of such and such a size.' We'd get the shoes, give him the potatoes, and bring them to the cook, who'd give us potatoes. So we got by.

Otherwise a person remembers very little, because when I talk with my friends, we can't agree on anything. Why? I say, 'I used to drive around with the Rollwagen.' Pavel Werner says, 'I also used to drive around with the Rollwagen!' I say that this and this happened. He says, 'It wasn't this, but that!' Each one something different. And when we already knew each other for a longer time, we remembered one single incident, which he began to talk about and I finished it. So I said to him, 'See, we really did ride together, and we've forgotten it all.' We really did forget everything.

In Auschwitz I met my uncle. He actually wasn't my uncle, but my father's cousin, we used to call him Uncle and he used to recall that he survived the concentration camp thanks to me. I don't know how I discovered him there, I only remember that I brought him a big, raw potato. For him it was a gift from heaven and he recalled that I also found him a warm sweater. Well, these are things that I don't remember at all. Some things a person remembers and other things disappear from his head.

In January [1944] they drove us out on a death march 8. It was ugly, because outside it was around minus twenty [degrees Centigrade] or more. After about three days they loaded us into open wagons - coal wagons. I remember that we were left standing at the station in Ostrava, on the first track. A girl came walking by, she might have been around 20, we could have been around 14-13 and Honza Sterbinger yelled at the girl, 'Little girl, throw us a bun,' because she was carrying a basket of rolls. She looked, took the basket and threw the whole thing to us into the wagon. Right away everyone was our friend. Otik Schön and his father managed to escape from our transport. Otta Schön was a well-known person [in Auschwitz], because they were locksmiths and made their rounds around the whole camp. His father wrote the book Death Factory [Schön, Erich: Death Factory; 1946]. At that time I was in Israel and Otik gave me that whole big story of his father's. I discovered that I was the only one that remembered how they escaped.

Otik and his father were in the wagon ahead of us. We remained standing, I was convinced that it was Studenka, and Otik explained to me that it wasn't Studenka, but Ostrava, where we had remained standing. Otik's father asked whether he could bring some water, because there was an old shed by the tracks, and somewhere behind it there was water. So he took a pail and went for water. He returned. He went a second time, brought back a second pail, distributed it, and took Otik with him and again went for water, but they never returned. And now I also have it from him in writing. So I remember this kind of rubbish and don't remember anything else any more, only that how in Mauthausen we were crossing the Danube over that large bridge. These are those gaps. We were in Mauthausen for only a short time, about ten days. From there they stuck us into Melk, that was a sub-camp somewhere in Austria. There we remained until April, when they stuck us back into Mauthausen. That was after the Mauthausen camp was bombed. It was very tragic. They drove us out on another march and we marched off to Gunskirchen. There we were about five days, and then the Americans freed us.

After the liberation we all came down with fleck typhus [spotted fever], so the Americans hustled us off into a hospital. They treated and fed us, and when we were partly fit, they drove us off to Hersching, that was an airport, and handed us over to the Russians. They stuck us on a boat and we went along the Danube to Melk, where the Russians already were. We were there for about a week or ten days. They then led us off to the station, stuck us on a train and we arrived in Vienna. We stood in Vienna for about two hours, then the train started moving and they drove us off to Vienna's New Town [Wiener Neustadt]. And from Vienna's New Town we marched off right smartly by foot to Bratislava.

In our group there were a lot of 'Czechoslovaks.' And these 'Czechoslovaks'... When we came to the lake Neusiedler See, between Vienna's New Town and Bratislava, that was close to the Hungarian border. We decided to spend the night there. In the evening there were about six hundred of us, and when we woke up there were about twenty of us left, because those 'Czechoslovaks' were actually Hungarians, who were afraid to admit they were Hungarians, that is, Hungarian Jews. They all ran away to the Russians in Hungary. The rest remained and that was us, from the original 97 boys.

From Bratislava we went by train to Prague and there we reported at the repatriation office, where they gave us some sort of identification and 500 crowns. Then they sent us to sleep at the Catholic charity. I remember that they wrung their hands above us and I know that those women gave each of us ten hard-boiled eggs: 'You wretches, look at you!' The next day I went to my uncle's, to Vojta's. My uncle of course didn't recognize me, and said, 'Who do you want to speak to?' I told him that with you, and only then did he recognize me. He had in the meantime been acting as guardian for my cousin Milan [Milan Fink - son of Jaroslav Fink], who later left for Israel. And so a friend of my father's, some Mr. Stumpf, became my guardian. In the first place, because we looked horrible, they put us in the Stirin chateau, me they put into a recovery camp in the Krkonose Mountains. I was there the entire summer, six weeks. They turned me into a human being.

I returned, I had no one, so I got my pick of where to go [to a home]. From the time I was small I had loved skiing and at the home in Jachymov that was a possibility, so that's why I picked that children's home. I was cared for by the state and by the county social welfare institution. First they put us into a children's home in Vlasta, in Jachymov. There, there were mainly boys whose parents had fallen during the Prague Insurrection. After I finished my compulsory schooling I had to go to another youth home, because I was no longer a child attending school, and so I moved to a youth home, and there I studied to be an electrician. In Vlasta I was the only Jewish boy, but then, when I moved to the youth home, there were older boys there, Jews, who were from [Subcarpathian] Ruthenia 9 and who had remained here. There were about four of them. In 1948 they then moved to Israel. In 1948 I started working at the Jachymov mines, but I wanted to live in Carlsbad. In Carlsbad the Jachymov mines had a huge number of spa buildings [also see Karlovy Vary] 10, where they put up their employees. Then they transferred me to Horni Slavkov, where they later gave me an apartment.

After the war I tried to catch up with everything that I had missed. I attended the movies like crazy. I had to catch up with everything that I had missed. I managed to go to Prague for a week, buy tickets, and in that week that I was there I saw 21 movies. Then I returned, contented, to Jachymov. It was this thirst that I had to quench, and we didn't have it in Jachymov. I had it planned out, because one movie theater played from three and another from six, so I made myself a timetable so that I would manage to see it all.

I didn't want to emigrate, though I had the opportunity. I never felt the need to leave Czechoslovakia and didn't have any reason to, either. I had an opportunity to go to Australia, but that didn't happen due to some administrative reasons. Then I corresponded with some family in Canada. I said to myself, why should I push myself into something, when I'm at home here, I'll stay here!

After the war, I didn't get back any of our property. Just one painting, which had been hidden with a Christian friend of my father's, my mother's books and photo albums, those were the things I got back, but those are only trifles. I know that my father had walled up some documents - insurance policies and a gold watch - Saffhausen, very heavy. When I went to pick those things up, I found that beside the hiding place there was a chimney, and everything in that box was burned and ruined. So nothing of that remained for me either.

As an employee of the Jachymov mines they didn't call me up for basic army service. Each year I got a sign: In the interests of the defense of the state, you will not be called up in the year XY for army service. When I got it the fourth time around, I said to myself, what the hell am I supposed to do? I was already 25, and boys went to the army at the age of 19. I had a friend of mine that was the commander of a military station in Carlsbad. I asked him what it was I should do? He told me that even so, I have to go do my army service, and that I should write them that I want to volunteer. Otherwise they'll keep on sending it to me, and I'll end up going into the army at the age of 30. And so I submitted a request, and in 1954 I started my army service in Rokycany.

But I served eleven months of my term in the worst unit, in Nitra. That was horrible army service, because it was a school for the training of automobile specialists, and every unit sent one or two people there. There were pilots, infantry, sappers, border guards, and they didn't know what they were supposed to do with us, so they gave us infantry training. And they really gave it to us, it was a terrible tragedy. Then, when I got back to my unit, that was a total vacation, but in Nitra, that was hard as nails. It was more than it was supposed to be. There they always put us on red alert on Friday late at night. They thought up horrible things, we had to pack everything up, they loaded us onto trucks and drove us off somewhere thirty - forty kilometers away, threw us out and said, 'Get your butts back into the barracks!' In the morning we'd arrive at the barracks, dog-tired, and right away: 'Whoever wants to go out on leave, do your cleanup duty, have a shower!' Of course no one wanted to. Everyone crawled into bed.

I know the whole of southwestern Slovakia, we used to practice driving all over there. I'll never forget how in Komarno they were picking melons and had them stacked by the side of the road. We were a convoy of about thirty cars, and the first one stopped and like locusts we soldiers loaded all the melons that were on the road into our cars. Those were adventures! Or in Nitra we used to go to Hrnciarovce, that's below Zobor [a hill above Nitra], where it was all Hungarians living there, who grew strawberries. Our barracks and training grounds were close by. Well, when the strawberries began to ripen in the fields, oh boy. And the Hungarians, those were battles! Us with weapons and them having a go at us with rakes, that was an international conflict over strawberries. Up on Zobor, in August, when the grapevines were ripening and when they announced an alert in the barracks, there'd be only about 20 percent of the soldiers there, the rest were up on Zobor picking grapes. We had fun, it wasn't again all that bad, just that it was really tough. In 1956 I returned home.

I met my first wife at work. She's named Marie Pavlinkova, and was born in 1935. She studied to be a cook, but worked in the Jachymov mines as an operator, she looked for radioactive traces. Our wedding was in 1952. We had two daughters: Vratislava in 1953, and Jenny, who was named after my grandmother, in 1958. Because I traveled a lot, to installations all over the republic and later even abroad, we began to have problems, which in 1969 resulted in a divorce. Maria and I used to live in Horni Slavkov in a three-room apartment. For some time after the divorce we lived under one roof.

In 1973 I got married for a second time, with Hannelore Miszcich. My second wife is of German origin. We met in Germany, because I used to go visit installation sites there. Our wedding was in Horni Slavkov. In Slavkov I was living in a small apartment, and because my wife said that she wouldn't live in such a hole - that apartment really was tiny - I took a job with a construction firm under the condition that they give me a three-room apartment in Ostrov. And as soon as they finished the prefab apartments in Carlsbad, we exchanged our huge apartment in Ostrov for our present one here in Carlsbad. An apartment in Carslbad suited us, and them the one in Ostrov, so everyone was happy.

Hannelore initially worked as a nurse at the university in Erfurt. They moved from Erfurt to Magdeburg, where we met, because I was working there too. We fell in love, came to an agreement and got married. After our wedding we lived in Slavkov. The first year she didn't work, so that she could learn the language, and then started working in Carlsbad at a spa, where she was assigned, because the spa was looking for nurses that spoke German, English and French, because of foreign clientele.

My wife has two boys from her first marriage. Tomas, who was born in 1961, and Matias, he was born in 1963. Both boys lived with us. The girls we split up. Jenny, the younger one, lived with her mother and Vratia [Vratislava] was with me. Well, and Tomas fell in love and moved away to Sokolov. Matias was with us up until his army service. During his service he got married and afterwards they [the state] gave him an apartment in Klasterec, so he moved to Klasterec.

All of our children attended elementary school in Slavkov. After she finished her compulsory schooling, Vratislava started working. She didn't want to go to school any more. She was always terribly hard-working. She wanted to work, to make money, and so that she could work with her hands. She was a crane operator. She worked her entire life for the Slavkov Construction Co. Vratislava isn't alive any longer. She died of cancer in 1992. She left behind three children, Janka [affectionate for Jana], Bohus and Standa [affectionate for Stanislav]. Vratislava married Bohus Silvar. He's also since died of cancer. It was a very unhappy marriage, and so she got divorced. The second time she married someone by the name of Konar, and that was also a very bad marriage. The youngest, Standa, was born of the second marriage.

Jenny graduated from nursing high school and works as a nurse. Jenny was also married twice. I don't remember her first husband, and the second is named Purkar, something like that. She has two children from her first marriage - Mirek and Hanka, and from the second marriage she has Veronika.

After the divorce in the beginning the girls could be together as much as they wanted, because we both lived in Slavkov, but then Marie remarried and moved away to be with her husband in Chomutov, and then they didn't see each other any more, only when Jenny came to visit us. From a young age the two girls had a bad relationship, they always fought and to this day I don't know why. One time it wasn't the way one would like, the next time the other, and right away things were bad. Even in adulthood they always argued, they could get along for only twenty minutes and then got into each other's hair.

My stepsons Tomas and Matias went to school in Slavkov. Tomas apprenticed in something, then graduated with honors and even graduated from university, as an engineer. He married Bozenka. They have two children, Tomas, who's also an engineer, and a daughter. They live in Kinsperk. Matias graduated from vocational school in Pilsen. Matias doesn't have a university education. Tomas started working for the Sokolov mines, and there he did things to do with computers. Later he and Bozena started their own company: they have 320 employees and five branch offices in Germany and also in Cyprus. Matias went to work in construction, where he worked with telemetry and control systems technology. He also started his own telemetry, control systems and air-conditioning company.

My children don't know anything about Judaism, because there weren't really any Jews left. Jenka and Vratia are half-Jewish, but I personally didn't know anything about it, because from childhood I had no affinity to it. I only remember one boy, from the 'Jugendheim' in Terezin, who constantly prayed. He was the only one that I met who had those tefillin tied around, and that box. He was swaying back and forth there, and we were talking about something, and he suddenly says that it couldn't be that way. And we retorted in unison: 'You're praying, so mind your own business, why are you listening to us?' This was the kind of relationship I had to religion, I had never seen it. It meant nothing to me, and I'm not even talking about Auschwitz, about Terezin...There can't be a God, and religion is nonsense.

In our spare time we often attended the theater with our family, here in Carlsbad. We attended performances when we could, because I was constantly away, mostly we picked operettas. We used to go on trips with the children, to Lipno and Orlik and so on. I always thought something up. [We went] to the High Tatras, to Dobsina to Mala Fatra. We really traveled a whole lot. We don't spend all that much time with our grandchildren, because Tomas's children have different interests, as Tomas is Mr. Big-businessman and our grandchildren act accordingly. We have a very good relationship with Matias' children from his first marriage, we used to see them a lot. He's also got two children from his second marriage, but we don't see them at all anymore, because he's getting divorced and she moved to Semily, and it's a rare event when he goes there for the children and comes over with them. For him a family visit means a thousand kilometers. And he's got them from Friday after lunch and on Sunday he drives them back. So we hardly see them any more.

I was very conscious of the coming of Communism in the year 1948 [see February 1948] 11, because I was a direct participant. At that time I was in Prague often, so I absolved all those demonstrations and conflicts in Prague. Everything took place on Wenceslaus Square, the crowds stood under Melantrich, those were National Socialists, so supporters of National Socialists also stood there. A bit further down, where Prace is, were on the other hand supporters of the Communists. And then they fought amongst each other. I liked it, I only remember that I was running and I remember someone climbing up on the podium and yelling: 'Comrades!', they fell quiet and he yelled again: 'you'll get your asses kicked!' And I enthusiastically began to applaud, there were more of us, and then the Communists started to chase us, so we had to run, but these are these adolescent experiences.

I never had any problems during Communist times. To us it seemed that it was normal, that that's the way things have to be, because a person didn't know anything else. Those childhood memories were so small and faint, that it was automatic for me. When I needed shoes, they looked into the records and said: 'yes, your last shoe voucher was a half-year ago, so you're entitled to new ones!' They gave me a voucher and I went to the store to buy shoes. That's how it was. In principle these things weren't available, but in this way you could get them.

I myself was never a member of any party, and neither did it interest me. I didn't pay any attention at all to the Slansky trials 12. They didn't interest me, because I was at the ends of the earth. Those were the 1950s, and though I was already living in Carslbad, I worked in Slavkov. That means that my bus left at 3:30am. A person came home after the afternoon shift, and I was young, so we'd go out somewhere, and then in the evening, quickly into bed, to get up at 3 in the morning. And those were the things that interested me.

The year 1968 [see Prague Spring] 13 was more interesting, because I was already an adult, I was working in Slavkov and had a company service vehicle and was on the road a lot, so on our way we'd turn the road signs around so that the Russians wouldn't have it so easy. We also went to Slovakia, where we bought some cherries, but at that time there was a heat wave, and they began to ripen too fast. Someplace before Vysoke Myto [Usti nad Orlici county] we overtook some Russian car and began to throw rotten cherries into it. Well, and then we quickly stepped on the gas, so that they wouldn't catch up to us. So those were my experiences from the year 1968, on the whole I enjoyed it.

In 1968 I had a boss who said that we have to go and check out how things are in our country. On 21st October we set out for Prague. They didn't want to let us in, because it was closed off, but they finally let us in, we told them some tale, that we had to go there. We even participated in a couple of demonstrations, and got tear-gassed on Old Town Square. From there we went to Olomouc, where there was also some sort of brouhaha going on. We wanted to go for supper and a cop stopped us and said to us, 'Mr. Driver, your eyes are red! I'm not letting you go anywhere, I'm going to make you go lie down!' I said, 'Mr. SNB [in Czech the initials of the National Security Corps, were used by the police in those days] - if your colleagues in Prague didn't fire tear gas at me, my eyes wouldn't be red!' In the end he let us go and we ended up in Zlin.

There it was also surrounded, thousands of the People's Militia in front of the hotel, saying that we really can't go in! So we started in on them, and got into the hotel for supper. We continued on to Brno, where they had declared martial law, so we'd have some more fun. People were staring at us and asking why were we driving around when there's martial law? I said, 'How am I supposed to know that, no one told us anything!' Those were interesting times, and when we were leaving our hotel the next day, we forgot our identification there. We traveled the whole way from Brno without any ID, but luckily no one else stopped us.

The years 1988 and 1989 [see Velvet Revolution] 11 were also interesting, because no one knew ahead of time what was really going on. Because the revolution started with the students, they began to stand guard in front of the schools and so on, and talked to people, tried to convince them. And when that was going on, a person really only slowly and with difficulty came upon what it was really all about. Anyways, it ended up the way it ended up. I think that it was a big mistake that the Czechoslovak Republic was split up after the revolution. I've been to Slovakia many times, and very much like Slovaks and Slovakia.

To be honest, the creation of Israel didn't evoke any sort of reaction in me. I didn't care one way or the other. I remember that my cousin flew there when they were training students there, he left on the same plane as they did. Otherwise I've never heard anything about it. He didn't associate with me, only with my uncle. He then worked at the airport in Tel Aviv, he had some sort of position there. He stayed there up until his death. Only now have I begun to take an interest in the situation in Israel, because I was on vacation there. We had good weather, because it wasn't that hot there yet, only about 32 degrees. It was a very nice trip. I met my friends from the concentration camp there.

My relationship to Judaism didn't really change, even after the fall of Communism. To tell the truth, I've never had much love for those Orthodox ones. I never could stand them, and I can't stand them today either. By me they aren't normal people, they're they same types of lunatics as those Muslims, who are capable of anything and will never think in a normal fashion. It's already been about 25 years since I've registered myself in the Jewish community. I don't go to prayers. I only go there once a year for a meeting. When there was still a prayer hall on Masarykova Street, the old man that was always there would pick up the phone and say: 'Look, I need you to come on Saturday, buy yourself a paper, you can read the paper there!' I said, 'What am I going to do, when that God will look at me and I'll be reading the paper!' 'That doesn't matter, but you'll be the tenth one!' They needed a minyan. That's about my approach to it, but my approach is the same as probably everyone's, because even he told me to bring a paper, so I wouldn't be bored.

I got compensation for my parents, but subsequently also lost the money, because I had it deposited in a credit union that went bankrupt. Of course I got something back. I had two accounts there, after my mother and my father. There was 100,000 in each account, and when I submitted my claim, I went to a lawyer and signed everything. I went to get the money, I was supposed to get 90 percent. It somehow didn't seem right to me, and I asked why was I getting so little? And to this they said, 'For the first one you'll get 90 percent and for the second 25 percent!' I didn't know that.

At that time my wife was in Germany, because after 1989 she went there to work. She was there until 1998, so that she'd have some money on top of her pension. She gets a [monthly] pension of 420 EUR from Germany. My wife has two pensions, in the Czech Republic she has 19 years of employment, and in Germany she also has 19 years. Now she has around 5000 [5000 Czech crowns = 170 EUR] here and there she gets 420 EUR. We're not complaining, we've got it good.