Frieda Rudometova

Kherson

Ukraine

Interviewer: Zhanna Litinskaya

Date of interview: September 2003

Frieda Rudometova lives in a two-bedroom apartment in a standard 5-storied khrushchovka [1] built in the1960s Kherson. Frieda is a nice looking dark-haired lady with a short haircut. She is wearing a fancy blouse and a skirt. Her apartment is clean. There are flowers on the table and embroideries and copies of pictures on the walls. Frieda invites me for a cup of tea in the kitchen. The kitchen is also shiny clean. During our conversation the hostess gets often distracted: her neighbors or the girls who rent a bigger room from her come by. Frieda explains that she needs some additional earnings to her pension that is too small for her to make ends meet. However, she talks about her problems with a smile and she does not complain.

My farthest ancestor whom I knew was my paternal great grandmother Etl Berliand. I didn’t know her maiden name, though. Since the early 1920s our family has lived in Kiev. I often visited my great granny. Basically, the families of my parents came from Murafa, a small Jewish town in Vinnitsa region, about 300 km from Kiev. I visited Murafa in the middle 1930s and I liked the town. The nearest town to Murafa was Zhmerynka and there are other towns like Murafa in the nearest vicinity. Murafa is on the bank of the river with the same name, very picturesque, with green banks and reeds. Before the revolution of 1917 [2] 70% of the population consisted of poor uneducated Jews. They were craftsmen and had big families. Jews lived in the central part of the town. There was a market in the center where they had their shops and stores. There were tailors, shoemakers, carpenters and glass cutters. My grandmother told me there was a synagogue and cheder in the town, but this was before I went there. The soviet power destroyed [3] all religious buildings in the 1920s. After the Pale of Settlement [4] was canceled the family of my great granny Etl moved to Kiev escaping from never ending pogroms [5]. I don’t know where my great grandmother studied, but now I understand that she was a very educated woman – she read the Torah, Talmud and other books in Hebrew and Russia classics. Only few Jewish women knew Hebrew and could write in Russian. My great grandmother told me about Jewish traditions and religion and explained about the tallit and tefillin. She was too old to go to the synagogue, when I knew her. She was a housewife her whole life. When I remember her, she was about 100 years old, but she kept the apartment ideally clean and always cooked something delicious, when I came to see her: cookies or strudel. She stayed in bed most of the time in the last years of her life, but she had sound mind. My great grandmother died in the late 1920s at the age of 102. She was buried in the Lukianovskoye Jewish cemetery in Kiev according to the Jewish tradition.

My great grandmother had many children – eight, I guess, but I didn’t know them: after getting married they moved to other towns with their spouses. My great grandmother moved to Kiev with her younger daughter, my grandmother Pesia Ladinzon (nee Berliand) and her family. Grandmother Pesia and my great grandmother Etl lived in a small one-bedroom apartment in Krasnoarmeyskaya Street in the very center of Kiev.

My grandfather Yefim Ladinzon, born in Murafa in the 1860s, belonged to the Jewish intelligentsia: he was a pharmacist like his father. He owned a pharmaceutical storage facility supplying medications to the pharmacies of Murafa and other towns. He also owned a pharmacy. I don’t know whether my grandfather had special education or learned the pharmaceutical business from his father, but I know for sure that he was a well-educated Jew. He knew Hebrew and read the ancient religious books: the Torah and Talmud that he always kept with him. My grandmother Pesia, born in the early 1870s, was a housewife and took care of the children. Staying at home was customary with Jewish families before the revolution and some time after. There was one daughter and four sons in the family. The boys got a traditional Jewish education: they studied in cheder and a Jewish elementary school. Later they gave up observing Jewish traditions, but they all had Jewish spouses.

The oldest of the children was Malka, or, Manyusia, as she was affectionately called in the family. She was born around 1890. Malka helped her father in the pharmacy and married her second uncle Pinhus Schneider, who also worked in grandfather Yefim’s pharmacy. After the revolution of 1917 and the Civil War [6] they moved to Sevastopol and worked in a state owned pharmacy. Malka and Pinhus had the only son. His name was Yakov. He was born in Murafa in 1913. There is a common prejudice that children from related spouses are born with physical or mental defects, but Yakov had none. He studied successfully at school, finished the Faculty of Economics of a higher educational institution and worked many years as chief of the department of labor and salary of the Black Sea Fleet. Aunt Malka died in the middle 1960s. She had blood poisoning that resulted in psoriasis. Yakov died in Sevastopol recently at the age of a little under 90.

The next after Malka my father Samuel was born, and his brothers Abram, Grigoriy and Naum followed him 1-2 years one after another. Abram, Jewish Avraam, born in 1896, married the daughter of a rich merchant in Kiev Fane and lived in Kiev where he owned a restaurant before the revolution in 1917. After the revolution and NEP [7] Abram got adjusted to the new regime and gave his property away to the people’s power that appointed him director of the restaurant. Abram had a wife and two children: Lev and Lisa. They were very wealthy. In 1932 there was an audit at his work. This audit discovered some violations, and Abram’s family left Kiev in a rush without telling anybody. Only a year later they wrote us from Leningrad. During the Great Patriotic War [8] Abram, his wife and Lisa evacuated to Samarkand. Continuous dust storms aggravated his chronic lung disease. Abram died in 1943. Lev was recruited to the front in the first days of the war and perished. I had no information about Lisa for many years. Only a year ago I heard that she lives in the USA. I wrote her, but there is no reply.

The next after Abram was Gershl (in the Soviet time he was called Grigoriy), born in 1898, took part in the Civil War and joined the communist party. After the war uncle Grigoriy also moved to Kiev. He was director of a restaurant at one time, then the party organs appointed him director of the first bakery factory. When the Great Patriotic War began he sent away his family – his wife and daughter Musia, while he himself stayed in Kiev at the assignment of the town committee for underground activities. He perished in Kiev few days before the Soviet troops entered the city in 1943, a former bakery employee, a policeman, reported on my uncle seeing him in the street. Grigoriy’s daughter Musia and her family live in Germany.

The youngest was my uncle Naum, born in 1900. He got a higher education finishing Kharkov Polytechnic College. His wife Anna was an obstetrician. When the Great Patriotic War began, Naum was recruited to the army and his wife Anna and their children Ada and Yefim, born few months before the war, evacuated to Kazakhstan. Grandmother Pesia was there with them. Naum perished in Byelorussia at the very beginning of the war. Ada lives in Germany; Yefim lives in Kharkov.

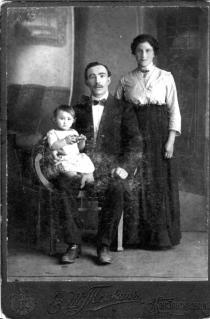

My father Samuel was born in Murafa in 1895. He was named Shloime at birth, but later, before obtaining a Soviet passport he changed his name to Samuel that sounded more familiar to him. Being the oldest son in the family he went to work after finishing the cheder. First he worked as a loader at my grandfather’s storage facility while gradually he studied the pharmaceutical business. My father was subject to military service during WWI, but grandfather Yefim didn’t want his older son to go to the war and paid for him to be released from service. My father grew up in a very religious family. He went to the synagogue with his father and at the age of 13 he had a bar mitzvah. Therefore, when the Civil War began, my father, being a religious man, strongly believed that it was against the human nature, something that his character and education could never agree to. Many other young men including his brother Grigoriy joined the revolutionary activities, but he stayed with his parents. Somehow he met my mother, and I think they met with the help of matchmakers, and they got married in 1918.

As for my mother’s parents, I know even less about them than about my father’s parents. My maternal grandfather Berl Winner was born in the small Jewish town of Krasnoye near Murafa in the 1860s. He got married and the young couple lived with his wife’s parents. Berl had two children in this marriage: Berla, the daughter, lived with her husband in Vinnitsa region. She died in the 1930s. Then a boy was born. He was retarded and suffered from acute schizophrenia. He died before turning 13. Shortly afterward Berla died, too. My grandfather remarried, and his second marriage was more fortunate. In the 1890s he married Feiga, a young girl from Murafa. They had two girls, born one after another. My mother Revekka, was a younger daughter. My mother’s older sister Maria, born in 1899, lived in Kharkov after the revolution. She was director of a kindergarten. I didn’t have any contacts with them and don’t know what happened to her or her son during the Great Patriotic War , Berl was a craftsmen, but I don’t know what exactly he was doing. His family was rather poor: they rented two little rooms. Berl and Feiga raised their girls Jewish. They observed Jewish traditions, followed kashrut, celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays and fasted on Yom Kippur.

My mother Revekka Winner was born in 1900. She helped her mother Feiga about the house before getting married. My mother had no education: my grandfather could not afford to pay for a teacher, but she studied in an elementary Jewish school for a year or two. Revekka was very quiet, even phlegmatic. She was a very tight-lipped person. I am sure that her marriage was prearranged by shadkhanim considering her personality.

My parents got married in 1918. Of course, there was a chuppah at the synagogue, but there was no big wedding party due to the hard times: this was the period of the civil war, when the power switched from one group to another resulting in pogroms. After the wedding the newly weds settled down in grandfather Yefim’s house that was bigger and more comfortable than my mother parents’ apartment.

Here, in the basement of my grandfather’s house I Frieda Ladinzon, was born on 17 June 1919. At this time there were Petlura troops [9], in the town and Jews were hiding away. Our family and few neighbors’ families were hiding in the big basement of my grandfather’s house. My mother’s neighbor Hilia was a midwife for my mother. The woman had many children and was quite capable of helping my mother. In early 1920, when I was a little over six months, my parents, my grandmother and grandfather Ladinzons and my father’s brothers left the house and all their belongings to move for Kiev escaping from continuing pogroms. Actually, by this time the family of my grandfather and father was miserably poor after so many pogroms and robberies.

Uncle Abram lived in Kiev. He was rich and bought a two-bedroom apartment in the center of Kiev in Shota Rustaveli Street for us, and a good big room in an old building in Krasnoarmeyskaya Street. Our family was very poor and if it hadn’t been for my uncle Abram’s support we wouldn’t have survived the famine in the 1920s. My father didn’t have a job. I remember that one time he unloaded buns in the private bakery in the yard of our house. I often came to the bakery and occasionally I got a hot bun – this was a delicacy.

One of my earliest memories was my grandfather Yefim’s death and funeral. He died in January 1924 around the time when Lenin died [10]. I remember my father and his brothers discussing that they could not make arrangements for my grandfather to be buried due to Lenin’s death. My grandfather’s body was lying on the floor wrapped in cerements. I remember my mother and other women sitting on the floor in torn clothes wailing. A rabbi and cantor from the Brodskiy [Brodski family – Russian sugar manufacturers. They started sugar manufacturing business in 1840s. Organized the 1st sugar syndicate in Russia in (1887). Sponsored construction of hospitals and asylums in Kiev and other towns in Russia, including the biggest and most beautiful synagogue in Kiev] synagogue located in Shota Rustaveli Street came to recite the mourning prayer after my grandfather. My grandfather was carried to the cemetery wrapped in cerements. The other children and I stayed at home.

My next memory is the birth of my sister about two months later in 1924. She was named Yelizaveta after our great grandmother – only I don’t remember whether it the grandmother on my mother or father’s side. Everybody called her Lisa. My father had a permanent job at the ‘Tochelectropribor’ (electric devices) plant. My mother was a housewife. After Lisa was born, and her delivery had complications, my mother became weird. She could sit idly staring into one point for hours. She didn’t cook. She happened to suffer from schizophrenia from her teens, but it was kept a secret from my father, but he would have never married her had he known. My mother had to stay in mental hospital for long periods. My father and I visited her on Sundays. She was quiet and looked enlightened when we came to see her in the hospital located on a high hill and it was hard to believe that mother was ill.

My grandmother Pesia took care of us. She either stayed with us or we went to her house to stay there a week or so. We went to the synagogue for women near the Brodskiy synagogue with my grandmother. On Jewish holidays uncle Abram and his family and we went to the Brodskiy synagogue. Uncle Grisha was a communist, and his family did not celebrate Jewish holidays. We often celebrated Sabbath in our grandmother’s home. There was a freshly baked challah, wine and delicious food on the table. Uncle Abram’s family also celebrated Sabbath with us. My great grandm9other Etl lit candles and later my grandmother took over this duty. We celebrated all holidays with my grandmother: I remember fancy crockery on Pesach, my grandmother kept it in a box, delicious potato pancakes on Chanukkah and hamantashen on Purim. We didn’t have any of these at our home because our mother was ill. Our family was much poorer than my father brothers’ families.

Grandfather Berl from Murafa visited us twice, when I was a child. He brought us cottage cheese and sour cream and ‘rooster-shaped’ lolly pops for Lisa and me. He visited us last in 1926. He died a year later.

I went to the Russian school on the fifth floor of a standard apartment house near our houses in 1927. After finishing the third form we were taken to a big school in Vladimirskaya Street. There were many Jewish children in my class. I had Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish friends. We got along well and I never heard ay abusive words against Jews from my classmates. The teachers also made no segregation among us. As for me, they were particularly sympathetic. During the famine in Ukraine in the early 1930s [11] our family was probably in a more miserable situation than the others. In summer 1932 my father moved to his sister in Balaklava (a town near Sevastopol). He explained that he wanted to find a good job there to support us better, but when I grew up I realized that just left my mother; he got tired of her disease, fault-finding and of the misery of life. He probably intended to support us, but he couldn’t find a decent job there. My mother, during intervals between attacks of her disease and her retirement to the hospital worked in a cafeteria washing dishes and peeling potatoes and vegetables. We probably wouldn’t have survived the hungry years, if it hadn’t been for my father brothers’ support. I often ran to uncle Grisha’s beautiful 3-storied house in Kreschatik Street [Kreschatik is the main street of Kiev]. They always had a good dinner at home. Uncle Abram sent us dried brown crust that my mother soaked in water for us. Our everyday food on these days was plum jam made from the plums that I picked from trees in summer and soup with a bit of flour.

It was hard for my mother to raise the two of us and I went to live with grandmother Pesia. I liked it more with my grandmother, she was very kind to me. I remember that she took some spoons to the torgsin store [12] to buy me food. Once she bought me a fancy red beret that was in fashion then. My grandmother also cooked for my mother and Lisa and I took the food to them. We exchanged our two-bedroom apartment for a room in Krasnoarmeyskaya Street near where grandmother lived.

Despite difficult circumstances, I was a cheerful and pretty girl. I studied well at school and took an active part in Pioneer and Komsomol [13] activities: I mainly helped those who had problems with their studies. I also participated in preparations to the school meetings dedicated to anniversaries of the October revolution and 1 May. I liked going to parades with my classmates. We didn’t celebrate revolutionary holidays at my grandmother’s home, but I knew all Jewish holidays. She celebrated Sabbath and this was sacred for her, and other holidays, and I went to the synagogue with her. However, sometimes I became naughty and brought home the pork sausage that my friends treated me to. My grandmother got angry with me and I laughed.

I finished my 7th form in 1935. I could continue my studies, but I knew I had to go to work to support my mother. My grandmother’s neighbor working in the security of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the USSR, took me there to get an employment. I talked with Satin, a Jew, who was business manager. I worked as a courier and then went to the school in the Central Committee. I completed my secondary education. When they asked me what profession I wanted to study I almost pronounced that I wanted to be a cook. I was always hungry and my strongest desire was to eat my fill, but I was ashamed to say it and said that I wanted to be a telephone operator. I finished a course of few months and began to work as a telephone operator in the communications department of the central committee. These were the happiest years in my life. I knew all party leaders: Kosior [14], Postyshev [Pavel Postyshev (1887-1939), political activist. In 1926 he became secretary of the Central committee of the Communist party (of Bolsheviks) of Ukraine. In 1930-1933 secretary of the Central committee of the Communist party (of Bolsheviks), 1933 2nd secretary of the Central committee of the Communist party of Ukraine. Arrested in 1934-38. Rehabilitated posthumously], and I knew the voice of Stalin: I connected him through the governmental communication equipment. They were great people and they treated me, a poor Jewish girl so well giving me an opportunity to study. I received food coupons, garment and shoe coupons. I gained some weight, grew prettier and made many friends. My close friend Lenochka, the daughter of a frontier colonel, and I often went to walk on the Dnieper slopes where there was a brass orchestra playing. I loved dancing and often went to the dancing ground. The horrific 1930s [15] were on their way. I never thought why the boards on the party boss’ offices were often replaced and the people working in them disappeared to be later declared ‘enemies of the people’ [16]. Kosior and Postyshev disappeared, and so did humble human resource manager Satin and many others. Once I asked Lena’s father about it, and he advised me to never ask these questions, so I didn’t. I was young and didn’t want to think negative: we believed in communist ideas and credibility of everything happening in our great country.

In 1936 I had my first vacation. I took half of it: in May I went to my hometown of Murafa – I felt like visiting the town where I was born. My grandmother Feiga, whom I had never seen before, lived in Murafa. I plunged into the Jewish way of life that still existed in the town. We went to the synagogue, celebrated Sabbath according to all rules, went to the cemetery where grandfather Berl was buried. I was young and wanted to go to the new club to dance. There was an amateur orchestra playing: two Jewish violinists, a pianist and a drummer. The public also danced tango and waltz that had recently become in fashion. However, when they played Jewish music, everybody joined in dancing: freilakh in the circle and other dances. I met my distant relatives: uncle Grigoriy wife’s sister and her children, and we became friends. They all perished in Murafa during the Great Patriotic War. As for my grandmother Feiga, I saw her for the first and the last time in my life. She died in 1939.

That same summer I visited my father in Balaklava where he lived in a small room in the basement. When we met, we both cried: I forgave my father for having left us. He was not happy. He worked as a night man: he never managed to get a job in a pharmacy by his specialty. I spent two weeks with my father. I never saw him again: he was arrested in 1937. Even night men could be declared enemies of the people or spies at the time for a joke told at the wrong time and at the wrong place. This happened to my father. My father was taken to a camp in Komi ASSR. My grandmother Pesia wrote him letters, but I was afraid of corresponding with him, and asked her to not even mention anything about me. I understood that I would be fired if this happened. My father started work at the wood cutting ground, but later he was transferred to the pharmacy in the camp. In 1938 my grandmother went to visit uncle Abram in Leningrad, but then she stayed to live there. From there she sent my father my photograph in 1940. I was immediately invited to the human resource office where they offered me to resign. They never explained for what reason, but it was clear that it happened because of my father. What was surprising was that I had worked three years before they disclosed this information about my father: a daughter of an enemy of the people could not be allowed to work in party organs. My father died in 1940. My grandmother and I got to know this after the Great Patriotic War, when my father was rehabilitated posthumously in the 1950s.

I went to work as a telephone operator at the shipyard and repair shop ‘Leninskaya Kuznia’. My mother often went to hospital. My sister Lisa went to work at the registry office in a big polyclinic after finishing the 7th form. Lisa’s dream was to become a doctor or at least, a medical nurse.

I lived in my grandmother’s room, but I often went to visit my mother and sister. Life was gradually improving: Lisa and I earned our salaries and my mother didn’t have to peel potatoes to earn her living. On 22 June 1941 the Great Patriotic War began. Kiev was bombed on the very first day. We woke up hearing a distant roar, but it could never occur to us that these could be fascist aircraft. In the afternoon Molotov [17] spoke on the radio about the treacherous attack of Hitler armies. It was a complete surprise for me. In early July 1941 the shipyard where I was working began to prepare for evacuation: its equipment was shipped to Zelenodolsk Tatar ASSR by train. The management and engineering staff also went by this train, but there was no organized evacuation of workers or such common employees as I was. Basically, nobody ever mentioned that Jews were to evacuate in the first turn. The district Komsomol committee sent my sister Lisa to dig trenches in the Western area.

I continued going to work, helping to load the equipment and being on duty at the telephone station of the plant. In middle August, before the last train with employees was to depart, my boss, a Jew, said to me: ‘If you want to leave the town, run home to pick your documents and come back – the train is leaving soon’. I rushed home. I only had time to grab my passport, my Komsomol membership card and a change of underwear and clothing. This was all I had with me: no warm winter clothes or bed sheets. I didn’t go to see my mother: I could not take her with me and I didn’t have time to say ‘good byes’. Besides, like everybody else, I thought we would be back in two months’ time. As for me sister, she wasn’t at home: she was at the digging of trenches.

I ran back to the railway station and boarded the train. It was a freight train and we slept on plank beds. When the train was crossing the Dnieper over the railroad bridge, it was bombed for the first time. It was stupid, but I got so scared that I climbed under the plank bed. The train often stopped to let the troops going in the western direction pass. There was a fierce bombing near Bahmach. Half of the train was destroyed and we had to wait for a replacement of the damaged railcars. I met my distant relatives in Bahmach: Musia, uncle Grigoriy’s daughter. She told me she was evacuating with her mother, and her father stayed in Kiev. Few minutes late I met Zhenia Kligman, my grandmother’s cousin sister, with her family. They were surprised that I managed to leave Kiev, but neither Musia nor Zhenia offered me to join them. All other plant employees were with their families, but nobody suggested that I took my family with me. I felt bitter and hurt. Besides, I didn’t even have food with me. The other shared their food with me, however. My boss whose name I don’t remember regretfully, and his wife Sonia were particularly kind to me. They had no children and they cared about me. We occasionally had soup and porridge at bigger stations and at times we only managed to get some boiled water and some junk food.

In about 3 weeks we arrived at the point of destination: Zelenodolsk town, 2000 kilometers from home. Zelenodolsk was a small town on the steep bank of the Volga in about 40 km from Kazan, the capital of Tataria. I was accommodated in a dormitory where thanks to my boss’ arrangements, I could have a little 6-square meter room for myself, and went to work as a telephone operator. There was a bed, a table and chair in my room where I stayed till 1943. However hard yeas these were I recall them with warmth. Firstly, this was my youth. Secondly, through all these years the Soviet people were united with their common trouble. People were kind to one another and treated me well. We worked 3 shifts, and at pressing moments I went to work as a worker and I did it believing that it was my duty to work where required. I also had a big workload at my place receiving telephone messages from the center, making reports of work completed and connecting bosses with the Kremlin since our plant worked for the front. Of course, life was hard, but I was used to hunger and endured it easier than those having a good life and plenty of food before the war. I had many friends and there were Jews among them. I was particularly close with Sonia and her husband. They tried to celebrate Jewish holidays even in the evacuation. They fasted on Yom Kippur and celebrated Pesach. They always invited me to join them on holidays. Though I was not religious, I began to fast on Yom Kippur. By this time we already knew about fascist atrocities against Jews and about Babi Yar [18]. I knew that my mother and sister perished most likely. I wrote them many times, but never got their response. Of course, I blamed myself that I didn’t say good bye or take them with me, but what could I do? It was a miracle that I managed to leave. Well, what do I say? I was young and my friends and I often went to the club and cinema and dancing.

On 2 May 1943 my friend and I went to dance at the plywood factory club. I put on my new dress made from the cut of fabric that the trade union department gave me as a gif. A tall slim sailor invited me to a dance. We met: his name was Pyotr Rudometov. We dated few months and he proposed to me on 6 November 1943. This was a double holiday for me: our army liberated Kiev and also Pyotr and I entered the local registry office at 5 o’clock before it’s closure. The registry clerk was hurrying home and didn’t want to register our marriage, but Pyotr convinced her to do it telling her that on this day Kiev, the town of his beloved girl, was liberated. We got married and celebrated the wedding in the dormitory.

My husband Pyotr Rudometov, Russian, was born in Kharkov in 1918. His parents lived there. Pyotr’s father perished during the Civil War and his mother and little Pyotr moved to Arudovo village near Kalinin where she came from. After finishing school Pyotr entered a Navy school in Leningrad. When the Great Patriotic War began, Pyotr was sent to a short-term course in Batumi and then – to the ‘Stremitelniy’ cruiser ship. Pyotr was wounded and sell-shocked near Sevastopol. After recovery he was sent to serve on ‘Ohotnik’, a small boat in the rear Navy unit in Zelenodolsk. Shortly after we got married Pyotr was sent to Batumi and our wanderings began. In 1944 Pyotr was sent to Poti where I met aunt Manyusia, who was in evacuation there. In a month or two Pyotr was sent to serve in Kronshtadt. I was pregnant. Our trip lasted about three months. I started labor when we were approaching Kronshtadt. The medical nurse of the crew got scared. He said he had just finished his medical school and had no idea of deliveries. The wife of commanding officer tended to me, when my first girl was born. I had mastitis and puerperal fever, and other sailors tore beds sheets to make bandages. In Kronshtadt we were taken to hospital. I recovered, but my girl Luda died. The personnel bathed her in cold water and the girl died from pneumonia. My second baby was born in Arudovo village where my husband’s mother lived, in December 1945. I named the girl Lisa after my sister. Pyotr was serving in our army in Germany at this time. I need to say that Pyotr was very good to me. My nationality didn’t matter to him. His mother also loved me. I tended to her better than her own daughters, but Pyotr’s older sisters Vera and Tania, in particular, continuously wrote him letters trying to convince him to part with the ‘zhydovka’ [kike], setting him against me. Pyotr came to take me with him and I was beside him ever since. Pyotr served in Liepaja, Latvia, 15 years. Our daughter Nathalia was born there in 1951, and in 1956 our son Sergei was born. We had a good life. My husband supported the family. I also worked as a telephone operator few years. The anti-Semitic campaigns of the late 1940s [19] had no impact on me; firstly because I was at home and secondly, because nobody ever asked me about my nationality while I had my husband’s Russian surname. Latvia was like a foreign country for the rest of the USSR. There were many goods quite inaccessible in other towns. And Pyotr’s sisters took to liking me all of a sudden. I sent them nice clothes. Upon demobilization Pyotr’s older sister Tania living in Kherson invited us there. She wrote about nice climate and plenty of fruit, and after demobilization we moved to Kherson.

I visited Kiev, my hometown, in 1948. Our neighbors told me that my mother was taken to Babi Yar on the 2nd or 3rd day of shootings: the janitor gave her away. Sister Lisa hid at her friend’s for few days, but then she went home to find out about her mother, and the same janitor reported on her. Lisa perished in Babi Yar in early October. They also told me about the tragic death of uncle Grigoriy: the loader who recognized him in the street reported on him in early November 1943, few days before Kiev was liberated. Grigoriy was also executed. For many years I used to visit Kiev almost every year to go to Babi Yar where my dear ones were lying, I went to Kreschatik and Shota Rustaveli Street where we lied. I still believe Kiev to be my home town. I am so happy that the Brodskiy synagogue where my grandmother and I used to go has been reconstructed and is a center of the Jewish life in Kiev.

Now about my grandmother Pesia. After the war she lived with aunt Manyusia in Sevastopol. I visited her several times. Sometimes I went to see her with my children. I felt myself Jewish in my grandmother’s house recalling Jewish traditions and customs. I could not celebrate holidays or observe Jewish traditions at my home: my husband Pyotr was a military man and a party member. With all his love to me he would not have allowed this. Grandmother Pesia died in the early 1960s at the age of over 90.

After we moved to Kherson my husband sailed on civilian boats for 11 years and later he worked at a factory. I stayed at home. Then my husband had a stroke and he was bedridden and couldn’t move for 3 years. Pyotr died in 1990, 3 years before our ‘golden wedding’ anniversary. Since then I’ve been alone.

My daughters have Russian spouses. My older daughter Yelizaveta Zakurakina finished the Pharmaceutical Faculty in Kherson. She has worked as a pharmacists in Chermon for 3 years. Her daughter Ludmila named after my first daughter finished a college, worked as a teacher at school, and now she works for a commercial company. My second grandson, Yelizaveta’s son Alexei, also works for this company.

Nathalia finished a Trade School and works in a big shopping center. Her marriage to Titkov failed. Her son Andrei from her first marriage died of sarcoma, her husband took to drinking and they divorced. Now she is married for the second time. Her surname is Harlova. Her daughter Tatiana finished a college and also works for a commercial company. She is single.

My youngest is my poor son, I don’t feel like recalling him. He is a finished alcoholic. He lives with his mistress and they both drank away everything he had at home. He has tuberculosis and on top of it all he broke his femoral neck bone and he is bedridden. He lives in terrible conditions and misery.

My husband died at the time of revival of the Jewish life in Ukraine and Kherson. I began to socialize with Jews, go to the synagogue. I observe Jewish traditions and light a candle on Sabbath. I’ve got new friends among the clients and employees of the Hesed in Kherson. I attend the Day Center in Hesed every week. I get to know about the Jewish history, culture and about Israel. After a recent surgery I have problems with my right hand, and a visiting nurse from the Hesed helps me around. While my husband was working, I had a good life. I only traveled to Kiev or Sevastopol to visit grandmother, but I couldn’t afford a vacation on the seashore or a health center. After perestroika [20], I receive a small pension for my husband since I hadn’t worked enough to have my own pension. I also lease one room to students. My daughters are well provided for, but they need to support their children. I like today’s living, when Jews have opportunities to live community life and they are not ashamed of their nationality and do not fear to hear the word ‘zhydovka’ like I did. My granddaughter Tatiana studied in Israel under an educational program. She likes this country and is eager to go there. She and Nathalia go to the synagogue on holidays. Therefore, the perestroika is good, for it supported restoration of the Jewry in the country and in my family.

GLOSSARY:

[1] Khrushchovka: Five-storied apartment buildings with small one, two or three-bedroom apartments, named after Nikita Khrushchev, head of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union after Stalin’s death. These apartment buildings were constructed in the framework of Khrushchev’s program of cheap dwelling in the new neighborhood of most Soviet cities.

[2] Russian Revolution of 1917: Revolution in which the tsarist regime was overthrown in the Russian Empire and, under Lenin, was replaced by the Bolshevik rule. The two phases of the Revolution were: February Revolution, which came about due to food and fuel shortages during World War I, and during which the tsar abdicated and a provisional government took over. The second phase took place in the form of a coup led by Lenin in October/November (October Revolution) and saw the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks.

[3] Struggle against religion: The 1930s was a time of anti-religion struggle in the USSR. In those years it was not safe to go to synagogue or to church. Places of worship, statues of saints, etc. were removed; rabbis, Orthodox and Roman Catholic priests disappeared behind KGB walls.

[4] Jewish Pale of Settlement: Certain provinces in the Russian Empire were designated for permanent Jewish residence and the Jewish population was only allowed to live in these areas. The Pale was first established by a decree by Catherine II in 1791. The regulation was in force until the Russian Revolution of 1917, although the limits of the Pale were modified several times. The Pale stretched from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia, almost 5 million people, lived there. The overwhelming majority of the Jews lived in the towns and shtetls of the Pale. Certain privileged groups of Jews, such as certain merchants, university graduates and craftsmen working in certain branches, were granted to live outside the borders of the Pale of Settlement permanently.

[5] Pogroms in Ukraine: In the 1920s there were many anti-Semitic gangs in Ukraine. They killed Jews and burnt their houses, they robbed their houses, raped women and killed children.

[6] Civil War (1918-1920): The Civil War between the Reds (the Bolsheviks) and the Whites (the anti-Bolsheviks), which broke out in early 1918, ravaged Russia until 1920. The Whites represented all shades of anti-communist groups – Russian army units from World War I, led by anti-Bolshevik officers, by anti-Bolshevik volunteers and some Mensheviks and Social Revolutionaries. Several of their leaders favored setting up a military dictatorship, but few were outspoken tsarists. Atrocities were committed throughout the Civil War by both sides. The Civil War ended with Bolshevik military victory, thanks to the lack of cooperation among the various White commanders and to the reorganization of the Red forces after Trotsky became commissar for war. It was won, however, only at the price of immense sacrifice; by 1920 Russia was ruined and devastated. In 1920 industrial production was reduced to 14% and agriculture to 50% as compared to 1913.

[7] The so-called New Economic Policy of the Soviet authorities was launched by Lenin in 1921. It meant that private business was allowed on a small scale in order to save the country ruined by the Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War. They allowed priority development of private capital and entrepreneurship. The NEP was gradually abandoned in the 1920s with the introduction of the planned economy.

[8] Great Patriotic War: On 22nd June 1941 at 5 o’clock in the morning Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union without declaring war. This was the beginning of the so-called Great Patriotic War. The German blitzkrieg, known as Operation Barbarossa, nearly succeeded in breaking the Soviet Union in the months that followed. Caught unprepared, the Soviet forces lost whole armies and vast quantities of equipment to the German onslaught in the first weeks of the war. By November 1941 the German army had seized the Ukrainian Republic, besieged Leningrad, the Soviet Union's second largest city, and threatened Moscow itself. The war ended for the Soviet Union on 9th May 1945.

[9] Petliura, Simon (1879-1926): Ukrainian politician, member of the Ukrainian Social Democratic Working Party, one of the leaders of Centralnaya Rada (Central Council), the national government of Ukraine (1917-1918). Military units under his command killed Jews during the Civil War in Ukraine. In the Soviet-Polish war he was on the side of Poland; in 1920 he emigrated. He was killed in Paris by the Jewish nationalist Schwarzbard in revenge for the pogroms against Jews in Ukraine.

[10] Lenin (1870-1924): Pseudonym of Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, the Russian Communist leader. A profound student of Marxism, and a revolutionary in the 1890s. He became the leader of the Bolshevik faction of the Social Democratic Party, whom he led to power in the coup d’état of 25th October 1917. Lenin became head of the Soviet state and retained this post until his death.

[11] Famine in Ukraine: In 1920 a deliberate famine was introduced in the Ukraine causing the death of millions of people. It was arranged in order to suppress those protesting peasants who did not want to join the collective farms. There was another dreadful deliberate famine in 1930-1934 in the Ukraine. The authorities took away the last food products from the peasants. People were dying in the streets, whole villages became deserted. The authorities arranged this specifically to suppress the rebellious peasants who did not want to accept Soviet power and join collective farms.

[12] Torgsin stores: Special retail stores, which were established in larger Russian cities in the 1920s with the purpose of selling goods to foreigners. Torgsins sold commodities that were in short supply for hard currency or exchanged them for gold and jewelry, accepting old coins as well. The real aim of this economic experiment that lasted for two years was to swindle out all gold and valuables from the population for the industrial development of the country.

[13] Komsomol: Communist youth political organization created in 1918. The task of the Komsomol was to spread of the ideas of communism and involve the worker and peasant youth in building the Soviet Union. The Komsomol also aimed at giving a communist upbringing by involving the worker youth in the political struggle, supplemented by theoretical education. The Komsomol was more popular than the Communist Party because with its aim of education people could accept uninitiated young proletarians, whereas party members had to have at least a minimal political qualification.

[14] Kossior, Stanislav (1889-1938): One of the founders of the Communist Party in Ukraine and General Secretary of the Communist Party from 1928-1938. He was arrested in the course of The Great Purges of 1936-38, known popularly as the Yezhovshchina (after NKVD chief Nikolai Yezhov who conducted them), and executed.

[15] Great Terror (1934-1938): During the Great Terror, or Great Purges, which included the notorious show trials of Stalin's former Bolshevik opponents in 1936-1938 and reached its peak in 1937 and 1938, millions of innocent Soviet citizens were sent off to labor camps or killed in prison. The major targets of the Great Terror were communists. Over half of the people who were arrested were members of the party at the time of their arrest. The armed forces, the Communist Party, and the government in general were purged of all allegedly dissident persons; the victims were generally sentenced to death or to long terms of hard labor. Much of the purge was carried out in secret, and only a few cases were tried in public ‘show trials’. By the time the terror subsided in 1939, Stalin had managed to bring both the Party and the public to a state of complete submission to his rule. Soviet society was so atomized and the people so fearful of reprisals that mass arrests were no longer necessary. Stalin ruled as absolute dictator of the Soviet Union until his death in March 1953.

[16] Enemy of the people: Soviet official term; euphemism used for real or assumed political opposition.

[17] Molotov, V. P. (1890-1986): Statesman and member of the Communist Party leadership. From 1939, Minister of Foreign Affairs. On June 22, 1941 he announced the German attack on the USSR on the radio. He and Eden also worked out the percentages agreement after the war, about Soviet and western spheres of influence in the new Europe.

[18] Babi Yar: Babi Yar is the site of the first mass shooting of Jews that was carried out openly by fascists. On 29th and 30th September 1941 33,771 Jews were shot there by a special SS unit and Ukrainian militia men. During the Nazi occupation of Kiev between 1941 and 1943 over a 100,000 people were killed in Babi Yar, most of whom were Jewish. The Germans tried in vain to efface the traces of the mass grave in August 1943 and the Soviet public learnt about mass murder after World War II.

[19] Campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’: The campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’, i.e. Jews, was initiated in articles in the central organs of the Communist Party in 1949. The campaign was directed primarily at the Jewish intelligentsia and it was the first public attack on Soviet Jews as Jews. ‘Cosmopolitans’ writers were accused of hating the Russian people, of supporting Zionism, etc. Many Yiddish writers as well as the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee were arrested in November 1948 on charges that they maintained ties with Zionism and with American ‘imperialism’. They were executed secretly in 1952. The anti-Semitic Doctors’ Plot was launched in January 1953. A wave of anti-Semitism spread through the USSR. Jews were removed from their positions, and rumors of an imminent mass deportation of Jews to the eastern part of the USSR began to spread. Stalin’s death in March 1953 put an end to the campaign against ‘cosmopolitans’.

[20] Perestroika (Russian for restructuring): Soviet economic and social policy of the late 1980s, associated with the name of Soviet politician Mikhail Gorbachev. The term designated the attempts to transform the stagnant, inefficient command economy of the Soviet Union into a decentralized, market-oriented economy. Industrial managers and local government and party officials were granted greater autonomy, and open elections were introduced in an attempt to democratize the Communist Party organization. By 1991, perestroika was declining and was soon eclipsed by the dissolution of the USSR.