Frida Khatset

Ukraine

Kiev

Interviewer: Roman Lenchovskiy

Date of interview: November 2001

Frida Khatset lives in a two-room apartment in an apartment house, which was built before the revolution in 1917, in the center of Kiev. She has a spacious apartment with high ceilings. There are many pictures on the wall: most of them are ‘still life’ pictures given to her by her friends – artists. There is a high bookcase with Russian classic and modern books and special books related to history. Frida is a short plump woman with a tidy haircut. She was friendly, and willingly told the story of her life. We had a conversation sitting at the round table in her living room. Frida lives alone now. Her husband died over a year ago. Her son Georgi often comes to see her, no matter how busy he is. He lives nearby and often helps his mother to do things about the house. Frida’s granddaughter Elena and daughter-in-law Sveta often visit her. Her old acquaintances and former colleagues also call her on the phone or come to see her. Hesed provides her assistance: food packages. This helps her to overcome her solitude.

Family Background

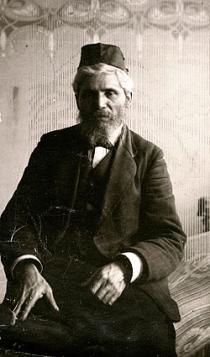

The name of my grandfather on my father’s side was Evzer Khatset. I guess my grandfather Evzer was born in 1850s. I don’t know where he was born. Perhaps, he came from Kiev. The thing is when we were young it was not a custom in our family to share the memories or ask questions about the past. My grandfather was a merchant of guild 2 1. He was a leather dealer. I remember how my grandfather looked: he wore a black yarmulka, had a small beard with streaks of gray and a moustache, and he was a slender man. My grandmother Haya Rukhlia Khatset – I don’t know her maiden name – was born in 1860s. I don’t know where she was born. My grandmother and grandfather lived near the synagogue named after Brodski 2 in the center of Kiev. My grandfather told me that this synagogue was built at the end of 19th century. I know that at that time almost half of all merchants were Jews and there were many flour grinding and sugar production enterprises in the town owned by Jews.

My grandmother and grandfather were deeply religious: my grandfather had a Torah and there was a mezuzah over their door: a box with a scroll with a prayer written on it. My grandfather had a black and cream striped tallit and a leather tefillin: two small boxes with long leather straps to be worn on the forehead and hands. My grandfather strictly observed Jewish traditions and went to the synagogue as long as his condition allowed. I remember that my mother and I went to my grandmother and grandfather when they were old and ill. I felt bored when she was taking care of them. Their apartment seemed very big to me: a big hallway, a dining room with high windows and several other rooms. My mother spoke Yiddish to my grandmother and grandfather and my grandfather spoke Russian with me since I didn’t know Yiddish. I can hardly remember my grandmother. Her condition was very poor and I wasn’t allowed to enter her room. I remember a big table covered with a long tablecloth in the dining room. I used to hide under the table shouting ‘Now seek me!’ There was a lamp in a beautiful shade with fringe over the table, a clock in the wooden casing with intricate carving, and the door panels were also decorated with carving. We have photos of my grandmother: she looks fat and kind, round-faced, with splendidly done hair wearing a magnificent hat with ostrich feathers.

My grandmother and grandfather had five children: the oldest girl Dunia was born in the end of 1870s. She married a Jew, I don’t remember her last name after she got married, but I know that she and her husband had a small house in Irpen near Kiev. Dunia was a housewife. I saw them several times when I was small. They visited us several times. I don’t think they had children. In 1941 when the Great Patriotic War 3 began my father was trying to convince them to evacuate, but they said ‘No, we shall stay in Irpen; nobody will do us any harm’. When we returned from evacuation in 1944 my father went to Irpen looking for Dunia. Her neighbors told him that in autumn 1941 Germans took Dunia and her husband to Babi Yar 4 where they perished.

Manya, the second daughter, was born in 1880. She graduated from the conservatory in Kiev and met her future husband there, he was a Jew. Manya took her husband’s last name, but I don’t remember it. I only remember that her husband’s name was Samoilik, he worked as a foreman at a construction site in Moscow. Manya went to live with him after they got married. Manya’s husband provided well for his family. She was a housewife. Samoilik had a son from his first marriage, I don’t know for what reason he divorced his first wife. He was a very handsome young man but he was killed in a shooting training shop, I know what my father told me. He and another young man courted one girl and somehow Samoilik's son was killed – nobody knew why or how. During the Great Patriotic War they stayed in Moscow. We didn’t see each other after the war. They only wrote letters occasionally. Manya died from cancer in Moscow in 1950s and uncle Samoilik lived few years longer.

The next was Gersh Khatset — he was the oldest brother. He was born around 1883. I don’t know whether he went to cheder. Gersh finished Commercial school in Kiev where they had advanced studies in commercial mathematics, commercial correspondence, commercial geography and accounting. Gersh received special secondary education in this school and entered Kiev Industrial College. Upon graduation from there he became a leather specialist. However, he couldn’t find a job according to his specialty and worked as an accountant. He was shortsighted and like my father, was not subject to military service. His wife Nina was Christian and Gersh was baptized too. My grandfather and grandmother were not happy about their son marrying a Christian girl and Gersh’s baptistery was a hard blow for them. But they could only but accept what happened. Gersh kept in touch with his parents, but they remained cold and polite with him and his wife, although they didn’t mind them visiting. I remember Gersh, Nina and their daughters Ira and Tamara visiting. Gersh’s or our family weren’t religious and we never touched upon any religious subjects. Before the Great Patriotic War they moved to Gorky – I guess they did it since Gersh couldn’t find a job in Kiev. I believe they stayed there during the war. Gersh worked as an accountant in Gorky. He retired and died from cancer shortly after the war in 1945. His wife died some time in 1950s. Tamara lived in Moscow and worked as a translator at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She knew French very well. She and Ira studied French when they were children. Ira became a doctor. She lives in Gorky, she sometimes calls me on my birthday.

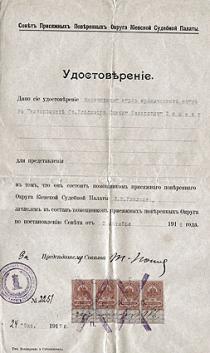

The next child in the family was my father Itshok Khatset, born in 1889. Like Gersh he studied at Commercial School in Kiev and finished it with a gold medal [highest award for graduates of secondary schools in the Tsarist Russia and after in former USSR] in 1906. To enter the University he had to pass exams for a course of studies in grammar school. My mother told me that my father's dream was to become a doctor and he submitted documents to Medical Faculty, but was not admitted due to the 5% restriction for admission of Jews 5. He studied at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics for a year and then went to study at the Medical Faculty, but left it. He spent a lot of time studying philosophy and literature and he decided that he had to refuse from becoming a doctor since he would experience the feeling of guilt every time he fails to cure a patient and every fatality would be painful for him. My father went to study at the Law Faculty believing that he would be helping people after getting this profession. He was a very sociable, kind and educated man and very intelligent person.

My father’s younger brother Boris was born in 1890s. Like Gersh he graduated from the Institute of Light Industry in Kiev and became chief engineer at the leather factory in Viatka. He was married to a Jewish woman and they had a son – Karik. In 1937, during the period of mass repression 6 Boris was arrested. At that time people were arrested for ‘political’ and other reasons. He was accused of supplying bad leather to make boots in the army. It was clear that the tendency was to eliminate intelligent people and this was openly said in our family since we were grown up enough to understand. Boris underwent tortures, but he didn’t sign the protocol. He was sent in exile somewhere in Siberia. When after 1953 the relevant authorities began to review all cases those that had not signed evidence papers were released. He was in exile for three years, but this had an ultimate impact on his life. When Boris was arrested his wife refused him. I don’t know whether she believed that Boris was an ‘enemy of the people’ or she just wanted to protect herself and her son from trouble. When Boris returned she forbade him to see his son. It was hard for Boris to bear exile and imprisonment and his wife’s retreat. He had no place to go to and he came to live in my father’s study. I remember that my father sent him to a recreation home to improve his health condition. My father also made arrangements for him to visit various doctors. He lived with us for a year until he got better. I guess, Boris stayed with us illegally since he was deprived of his right to reside in Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev. He was a skilled specialist and was employed at Viatka factory where they remembered him. He became a production engineer there, he was a highly qualified employee and much valued at work. He received an apartment in Viatka and married a Russian woman in few years. He wrote us that his second wife was a medical nurse, but we never saw her. Boris submitted a request for rehabilitation, but while his documents were under review he died. He was rehabilitated posthumously in 1956.

My father’s younger sister Vera Khatset was born in 1902. After the secondary school she graduated from Chemical Faculty of Kiev University and followed Manya to Moscow. Vera was single and had no children. She was a chemist and died in Moscow in 1970s. We didn’t keep in touch.

Before the revolution 1917 7 the Khatset family was wealthy: they could afford to take a vacation at the seashore in the Crimea or Caucasus. When the children grew up they didn’t make my grandmother happy: my father married a poor girl, Gersh got baptized that was even worse and Boris divorced his wife, although it was not his fault. I know that my grandfather and grandmother didn’t want my father to marry my mother. Especially my grandmother was against this marriage since my mother was a very poor Jewish girl having no parents while my father came from a wealthy family of a merchant and my grandmother believed he deserved a wealthier wife. My grandmother stated she would never give her consent to this marriage.

My mother’s father Borukh Rabin was presumably born in Boguslav [a small town in 100 km from Kiev] in 1850s and lived there his whole life. He was a craftsman, but I don’t know what exactly he was doing for a living. My mother said he was a gabe [senior man in Yiddish] at the synagogue and this was an elective position. My maternal grandmother Fruma Rabin (her maiden name is unknown) was born in 1850s and came from Boguslav. My grandmother and grandfather had six children. I don’t know their names since my mother’s brothers and sisters were 12-15 years older than my mother and my mother was the youngest in the family.

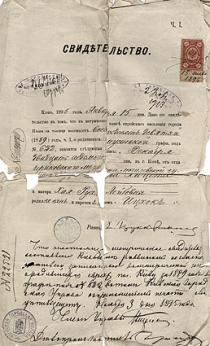

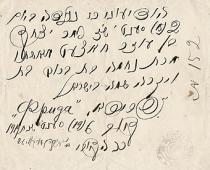

My mother Nehama Khatset (nee Rabin) was born in Boguslav on 8 October 1888. I have a copy of her Birth Certificate signed by the Korsun State Rabbi. At the age of 11 she lost her both parents. Her brothers and sisters had left their home long before. Therefore, my mother didn't remember much about her family. She only told me that they spoke Yiddish in the family and she spoke fluent Yiddish, too. Her parents were religious and observed all Jewish traditions. She lived with one or another sister and felt herself a burden. None of my mother’s brothers or sisters ever visited us. They didn’t keep in touch with my mother, and she was sad about it. My mother remembered that the majority of population in Boguslav was Jewish and Yiddish was commonly spoken everywhere. My mother finished a public secondary school in Boguslav.

At 16 she moved to Kiev having heard about a 3-year Frebel school 8. There were no residential restrictions to admission to this school. My mother went to study and rented a room in Shuliavka in the outskirts of Kiev. So my mother became independent at 16 and earned her own living. She went to work as a cashier at a vegetarian canteen in the center of the town. She was paid 3 rubles per month. The customers were students for the most part since this was an inexpensive canteen where they could get a sufficient meal for reasonable money. Being a first-year student my mother met my father that was a first-year student at the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics in Kiev St. Vladimir University. My mother had to take an exam in Latin at Frebel school. She needed a teacher and somebody recommended my father to her. It was a common thing that students earned money by giving classes.

My father began to teach my mother, but he didn’t charge her for his work knowing that all she had was 3 rubles per month. After my mother finished her first year at school it turned out that she needed a residential permit, or else she would have had to leave Kiev. In order for my mother to be able to continue her studies she and my father arranged a marriage of convenience in 1907. They went to have their marriage registered secretly in Kanev (100 km from Kiev) since my father’s parents were against their marriage. It was their big secret and my parents didn’t disclose it even to their friends or acquaintances. They did it to for my mother to be able to obtain a residential permit.

My mother went to school during a day and worked 2nd shift. For 7 years my mother was my father’s wife without entering into close relationships with him. I don’t think there are any idealists like them left. In 1913 my father had to terminate his studies at the University since he fell ill with tuberculosis and had to go take a treatment in Mentona, France, wealthy people used to travel to get the best medical treatment in Europe. He returned before World War I, passed his graduate exams in 1915 and became an attorney assistant. When my father began to earn his living he insisted that their pro forma marriage became actual. This happened in 1916. My mother didn’t agree to do it for two reasons: firstly, she knew that his parents, his mother in particular, were strongly against this marriage. My mother was poor, but proud. Secondly, my mother thought that my father wanted to consummate their marriage from the feeling of pity. He had to prove to her that this was love on his part. This lasted for several years before my mother finally agreed. I remember my mother’s landlady from Shuliavka visiting us before the Great Patriotic War. Every time she rang the doorbell she joked laughingly ‘Is your husband home, Miss?’ When my mother rented a room in Shuliavka and my father came to see her there this landlady said to mother ‘Your husband is here, Miss!’ After finishing Frebel school my mother continued working at the canteen until consummation of marriage. My father rented an apartment in the center of Kiev. In 1917 their first son Lev was born. My mother didn’t work since then. Later she finished a course of librarians and worked as a librarian before the Great Patriotic War and some time after.

Growing Up

I was born on 2 September 1919. I still have my Birth Certificate signed by the Kiev Rabbi. There was a number of Jewish pogroms 9 at that time and my mother came home from hospital with me a day after a pogrom. There was a Ukrainian janitor – Stepan, a strong broad shouldered man. He had no education, but was eager to study and my father was helping him. My mother told me that in a day or two after we returned from hospital bandits came to our house. We lived on the 2nd floor. Stepan told all tenants to close their doors and let nobody in. He stood by our door with an ax and said ‘You will only enter this apartment over my dead body!’ Pogrom makers retreated. Stepan always did physical work for us and brought wood for heating the house. He was very grateful for my father’s help. My father taught Stepan until he could go to study at rabfak 10. He finished rabfak and got a job at a housing agency. We loved and trusted Stepan.

At the end of 1919 Kiev was liberated from Denikin troops 11 by the Red army. My father was very enthusiastic about the Soviet power. All Jewish intellectuals believed this was a start of a new and bright life. My father became First legal advisor and then Head of Legal department of the Revolutionary Committee of the province and then – Provincial Executive Council, Town Council and Regional Executive committee.

In 1921 my younger brother Boris was born. I have dim memories about our apartment since I was too young. We lived in a 3-storied building. I remember our entrance to the building with a high front door and wide staircase with many stairs. We had a big apartment with high ceilings: a spacious dining room, my father’s office and a smaller children’s room with 3 beds in it. There was also my parents’ bedroom, kitchen, toilet and a bathroom. This apartment seemed huge to me. I remember a long hallway where my brother and I used to run playing. There was a homeopathic pharmacy, where they sold herbal medications, next door where my mother often left me when she had to go out. Employees there allowed me to play with drawers.

My parents spoke Russian to me and my brothers. Yiddish was their mother tongue and they spoke Yiddish with my grandmother and grandfather. We didn’t study Yiddish: there was a popular opinion at that time that young people wouldn’t need Yiddish in the future.

When grandmother died of cancer in 1923 my grandfather moved in with us and Yiddish sounded again in our apartment when my parents talked with grandfather. The children talked Russian with grandfather, but he spent little time with us. He spent almost all his time praying, we were not allowed to disturb him. My mother looked after grandfather since my grandfather was very ill when he joined us. He was grieving after my grandmother very much. He had a room of his own where we didn’t bother him. He was constantly praying and we were required to keep quiet and bother him not. We could talk with grandfather during dinner on Jewish holidays. On other days we had meals separately: my grandfather followed kashrut and my father came late from work and also had dinner by himself. Only on Jewish holidays we had meals sitting at a big table. My grandfather sat at the head of the table with his tallit on, but it was actually all done for my grandfather. I remember that my brothers and I were to sit at the table at Pesach, Purim and other Jewish holidays, but we couldn’t wait until we were allowed to leave the table to play. Our parents weren’t religious and didn’t observe any traditions, all they did was to show respect to grandfather. There is a ritual at Yom Kippur when a chicken is to be turned over one’s head and I didn’t want to have it done, but my mother insisted ‘You have to obey. It’s your grandfather’s wish’. My older brother was to find the matzah that grandfather hid under a pillow during seder at Pesach. We observed Jewish ritual only for grandfather’s sake and from the feeling of respect towards him. My brother’s and I often objected, but our father told us that we had to respect or grandfather’s feelings. Our grandfather had cancer and suffered a lot in the last two years of his life. He died in 1926. He was buried in accordance with Jewish customs, this was what father told us, we did not attend the funeral. My grandmother and grandfather were buried at the Jewish cemetery near Babi Yar. This area was graded later 12. My mother and we went there before the Great Patriotic War to cleanup the graves, but when my parents went there after we returned to Kiev when the war was over there were no graves at the area.

We didn’t celebrate any Soviet holidays when grandfather was with us. After our grandfather died in 1926 we didn’t speak Yiddish in the family.

Shortly after our grandfather died our father received an apartment in Kostyolnaya Street in the very center of Kiev. There were 4 rooms there: my parents’ bedroom, my father’s office, my brothers' room and a dining room where I lived. We didn’t light any candles or celebrate any Jewish holidays after grandfather died. This was a period of struggle against religion 13 we were raised as atheists at school and our parents created this atmosphere at home as well. Besides, our parents were not religious. We celebrated birthdays and a New Year. We always had a New Year Tree decorated at home, although it was not allowed by at that time. The Soviet power considered it to be vestige of the dark past, but we always had one anyway. We decorated the tree and in the morning of 1 January we found gifts under the tree. We believed that Santa Claus ( Granny frost – in Russia) brought them. Our father’s birthday on 9 January was the most festive celebration in our family when members of the family and friends came to greet him, there was no typical menu – just plenty of food. We still keep this tradition.

Before we went to school we had a governess: Olga, a German woman. She had graduated from Frebel school. She taught us the German language and my brothers and I knew German very well. She spent 5-6 hours every day with us. I have a good conduct of German even now. Our mother and father prepared us to school teaching us to read and write in Russian and count. In 1926 I went to take an entrance exam to a Russian school: since I could read and write in Russian and German I was admitted to the 2nd form. I remember a gym with high windows and a concert hall on the 4th floor. My brothers also studied in this school in the center of the town. The center of Kiev was populated by Party officials for the most part and their children studied in our school. There were 32 children in my class and 8 of them had the highest grades in all subjects. I was doing very well. I have bright memories about a bus tour to the woods in the outskirts of the city. We went to spend a day there and we enjoyed it a lot. I remember that I had Jewish friends in my class, although it wasn’t something that we did intentionally. We lived in the same street, went to school and home from school together. It was only after I grew up that I began to analyze and found out that there were Jewish children in our group while we didn’t even identify ourselves as Jews at that time. We remained friends for the rest of our life.

When I turned 10 I became a pioneer. There was an exciting ceremony when we had red neckties tied, it was a ceremony at the concert hall at school. We said an oath to be dedicated to the cause of Lenin and communist ideals. We always in school wore a pioneer uniform: a white shirt and a dark skirt or trousers. There were pioneer line meetings and pioneer competition in successes in studies and pioneer activities. There were teams of 5-6 pioneers formed: team members were children living in the same neighborhood and there had to be few weaker pupils in a team so that stronger ones helped them to catch up with the rest of their classmates in studies. I was a team leader and it was my task to push weaker pupils to be more thorough so that a whole team might get a higher grade for performance. I took every effort to make them study more and do their homework properly. I helped them after school. We did their homework together. Pupils also had to study a profession. We went to take training at the shoe factory located near our school. We made leather bags from leather wastes: those bags were sold. It is needless to say that we didn’t get any money for our work or get any profession there.

We always had newspapers at home: my father subscribed to ‘Pravda’ [founded in 1916, the biggest daily communist newspaper in the USSR] and ‘Izvestiya’ [a big daily communist newspaper] central newspapers. My brothers and I read them, but we always had to pile them on our father’s desk before he came home from work. We had a big collection of books and I read many Russian classical books, I liked Pushkin and Dostoevski. We had few books by Sholem Aleichem 14, a Jewish writer. I liked most of all his story ‘The Wandering Stars’. I read a lot and was very good at writing compositions at school. I discussed things with my father and valued his opinion highly. Our father returned from work late in the evening. In 1920– 30s he was a legal advisor at the town authorities and was always very busy. Our mother spent a lot of time with us. My father worked in his study even in the evenings and spent little time with us, but all the more we appreciated these sessions however short they were. We enjoyed talking with our father and always discussed interesting subject. Our father did not belong to the Party, I don’t know why he didn’t join it, but he knew the Marxism-Leninism philosophy. He was a teacher for many years and was awarded a title of ‘Red professor’ 15. He even had an appropriate certificate. My father wasn’t involved in any research work. There was a cult of my father in our family. He never did any work at home. Everything in the family served his interests. If he took a nap we tiptoed past his room not to disturb him.

During the period of famine in 1933 16 we saw swollen dying people in the streets. Many villagers moved to town hoping to survive. We had a housemaid, mother hired her when I went to school. She was a Ukrainian girl that lived with us and helped mother about the house. She brought her nephews and nieces to our apartment during this period and they lived with us, We played together. The children stayed in the living room. I remember that my brothers and I stood in long lines to get some bread.

There were few children from military families in our class. They were behind other children in their studies. One of such families where the father was a general lived in our house. They were wealthier than civilians. Once deputy director of our school called me and offered to give private classes to the general’s daughter who was in the 5th form, I was 15. I thought it was my pioneer duty to help this girl. I went there in the evening and said ‘Petr Mironovich asked me to assist your daughter with her studies’. The general said ‘Yes, he recommended you to me. What are your terms and how much do you charge? I had two classes per week with the girl and at the end of the month the general invited me to his office and paid me 3 rubles per each class. I didn’t want to take the money, but he said ‘Please take it. You work and need to be paid for work’. This was my first earning and afterward I always had private pupils. My younger brother Boris also earned money by giving private classes and we always had our own money and didn’t have to ask our parents about allowances we bought books and sweets and went to the cinema. It was a lot of money that we got for that time when a ticket to the cinema cost 30 kopek, an ice cream cost 10 kopek, a rather expensive book cost 1 ruble and a very expensive book cost 2 rubles.

In senior classes I joined the Komsomol 17. It was a mere formality at that time. We were not eager to become Komsomol members – I found reading and spending time with friends more interesting. We were just practical about our future possibilities with getting a higher education. As a part of public activities we collected steel scrap, but I was more involved in the issuance of the school wallpaper, political information classes that took part twice a week in the morning before school classes began. The one who prepared this information briefed the class on international events. It goes without saying that this information was based on newspaper publications. I was responsible for scheduling such briefings. We went to parades on 1 May and 7 November 18. We got together near our school and then marched along Kreschatik Street with the column of marchers. We didn’t celebrate 1 May or 7 November with the family. When we studied in senior classes we got together to celebrate Soviet holidays and to party. My parents didn’t mind having such parties at our home. My mother even preferred that we stayed at our home. She made cookies and pies and we had great parties turning our apartment upside down enjoying ourselves.

The children of Postyshev 19 studied at our school and Valentin, his older son, was in my class. There were children of officials of the Town and Regional Party committees and Central Committee of the Communist Party. In 1937 parents of many children were arrested. Their children were orphaned. Valentin Postyshev also became an orphan. We finished school in June 1937. I remember our prom: there was a ceremony at the concert hall and then we walked in the city that whole night singing. We were together until dawn. Valentin Postyshev entered the University. His father was in prison already and Valentin was expelled when he was a first-year student in 1938. He disappeared and I don’t know what happened to him further on. I remember the situation in 1937 well. As I already mentioned my father’s brother Boris was arrested at that time. We knew that Boris was no traitor and that it was a campaign against intellectuals. My father had more information, but he didn’t share it with us. He suspected that human rights were violated in courts, but never ever mentioned it. We witnessed something horrible when best professional, innocent people were declared ‘enemies of the people’. My brothers and I knew that under no circumstances we could talk about it at school. Teachers and other pupils kept silent, too. There was a lot of fear. Our father explained to us that such discussions might lead to arrest. In 1938 he retired from his position of Head of Legal department and took to advocacy.

I entered the Faculty of Chemistry in Kiev University in September 1937 without any problems. Since I had the highest grades in all subjects at school I just submitted my school certificate to the University and was admitted. There were Ukrainian, Russian and Jewish students at our faculty and the latter were in minority. We got along well and had no conflicts. This was the period when lecturers were required to teach in Ukrainian while many were used to read their lectures in Russian. Academician Yaglovskiy, our lecturer, usually asked us ‘You will not report on me to the Dean, will you?’ and continued speaking Russian.

I didn’t face anti-Semitism before the Great Patriotic War. I was a member of the trade union committee at the University. The trade union group was responsible for supporting students living in the hostel and making arrangements for their stay in recreation centers, - active Komosmol members and those that were a success in their studies went there. Students also had to participate in parades at Kreschatik 20 on November holidays [November 7] and on 1 May. By the way, the district Komsomol committee required that we came to the gathering spot 3 hours before a parade began. Because three hours prior to demonstration blocked all central part of city, transport did not go and to a place of the beginning of procession passed nobody.

While we were taking part in peaceful parades Jews were already exterminated in dozens of German and Austrian towns. There were rumors spread about the situation there, the first rumors appeared in 1940. Some people listened secretly to foreign radio channels and shared these bits of information with others. The Soviet radio kept silent in this regard and newspapers didn’t publish anything like this.

In 1939 when Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact 21 was executed when in 1940 the Baltic Republics and Ukraine joined the USSR newspapers described these events as great progress and strengthening of our borders. And the fact of Western Ukraine 22 joining the Soviet part of it was described and a great and happy event. We believed that it was true, this reunification of the nation.

During the War

In 1941 I finished 4 years of studies at the University and went to take a training course at the chemical factory in Slavuta in 300 kms from Kiev. On 22 June 1941 my fellow students and I were walking in the town on a lovely day – it was Sunday - when we heard Molotov’s speech on the radio. He declared that Hitler attacked the Soviet Union. It was a complete surprise for us. Radio and newspapers had convinced us that Hitler wouldn’t dare to attack the Soviet Union. We wanted to go to Kiev, but our management ordered us to stay until we completed our task. It was a problem to get on a train and director of the railway station pushed me into a railcar – his daughter also was far from home and he felt sorry for me especially thinking about his daughter that might also have to rely on somebody’s support. It took us about a week to get to Kiev since there were German bombers attacking us: the train stopped on the way and we scattered around hiding. At the beginning of July evacuation began in Kiev. My father worked as legal advisor at a military plant, and our family evacuated with the plant: my parents, Lev, Boris and I. My brothers were not mobilized to the front due to their poor sight. The train moved to the east. It was often bombed, but each time we escaped miraculously. When the train stopped we jumped out to get some water or buy some food. Our trip lasted for about 3 weeks until we finally arrived at Buzulk station near Kuibyshev, in 2500 kms from Kiev.

We were accommodated in a small room near the plant. There was a table and 2 beds in the room. My parents slept on a bigger bed, I slept on a smaller one and my brothers slept on the floor on some old rags. There was a small wood stoked stove in the corner where my mother cooked.

In August 1941 my father, brothers and I began to work at the military plant. This plant manufactured aircraft equipment. My father was a legal advisor and my brothers and I worked in shops 10 hours a day. We were provided with special clothing, winter coats and boots. This saved us during winter since we had very few things with us from Kiev: there was a common conviction that the war wouldn’t last longer than few months. Our mother did the housework. We received a small plot of land from the plant where we grew potatoes, pumpkins, onions and carrots, we ate everything that we grew, but this was not enough. We received food packages at the plant: cereals, bread and sometimes, so we didn’t starve.

The Kiev University was evacuated to Alma Ata, all the professors went there. I went there in September. I met my fellow students and we lived in the hostel. I didn’t stay long in Alma Ata. I prepared for graduation exams in 3 months and returned to Buzuluk with a degree.

I was leader of the Komsomol unit at the plant. I was responsible for political information and issuance of the plant newspaper. I also conducted classes for rabfak students, who were 12-14 year old children from occupied areas. They had lost their parents. I worked with the administration to resolve the issue of making provisions for these children and patronized them at the hostel. Management of the plant was pushing me to submit an application to join the Party, but I realized already that I wasn’t going to do that and just said that I needed time to grow to this level. I remembered 1937 well and lost faith in our leadership. There was an episode that proved my doubts to have grounds. I was a foreman at a shop and worked a night shift once. There were toxic chemical wastes in this shop. It was the last day of the month. Something went wrong with the conditioning system and the shop stopped its operations. Deputy director said to me ‘Recharge galvanic basins and load equipment since we disable the assembly line to continue their operations’. The 1st ship was responsible for this situation since they had to fix the equipment to support safe work conditions. It was a major violation of safety rules to recharge galvanic basins when the exhaust air funnel did not function, but I was still given an order to recharge the basin with a gas mask on. I removed all personnel except one worker to assist me. We recharged the basins. It usually took 1.5-2 hours to complete this process, but upon completion it was necessary to air the shop, but the air ventilation did not function. The worst thing was that there was potassium cyanide there that generated prussic acid. After recharge I had to close and seal potassium cyanide, but my gas mask glasses got fogged up. Since I couldn’t see anything I tried to feel the seal with my hands, but I couldn’t determine whether it was sealed or no. I had to make sure that this was done properly; if this had been done improperly I might have had to stand in court. I shifted my gas mask for an instant to make sure that it was sealed and headed to the exit. At that time there were blackouts required and when I opened the door the blackout was perpetrated: that was why they found me promptly. I fainted and recovered my conscience when two ambulance crews were giving me first medical aid. From the point of view of production needs this order was correct while from the point of view of health safety it wasn’t. I was severely poisoned and the management knew it was their fault. They sent me to recreation house for managerial personnel located near Kuibyshev. I had a room there and personnel brought me food into the room: sugar, butter, fruit and vegetables, and I thought I got all this food because I was ill. When I got better I went to the canteen one morning and saw tables covered with snow-white tablecloths and plenty of food on the tables that we hadn’t seen since the war began. There were few women sitting at tables. It was the same at lunchtime and in the evening high-rank men came to dinner. They had dinner and stayed overnight and went to work in the morning. That was when I realized what kind of life officials led. The war revealed that there was one truth for our leadership and another truth – for people.

After I returned my management insisted that I submitted my application to the Party. I just had to do it or otherwise I might have been suspected of having anti-Soviet opinions. My application was approved by the plant Party unit meeting. Then at the end of April I left for Kiev and I never showed this approved application to any other authorities. Some of my acquaintances were devoted Bolsheviks. They sincerely believed in wonderful communist slogans that promised beautiful life in the near future…

I met my future husband Alfred Lieberman at the construction unit at the plant. He told me that he was from Kiev and lived in a neighboring street. Alfred was born in Kiev in 1914. His father was a legal advisor in the Ukrainian Red Cross in Kiev. My father knew him. Alfred’s mother was a housewife. Alfred was a construction engineer. On the first days of the war he was assigned to Design Department of Kiev Regiment and he was not subject to demobilization to the front. In August 1941 he was transferred to the construction of military sites at the Volga defense line in Ulianovsk, Saratov, Kuibyshev and Buzuluk. When Alfred and I met at the plant my father invited him to our home. I liked Alfred. He was an intelligent man. We began to see each other walking in the town or visiting friends and went home in Kiev together in 1944.

My father returned to Kiev in February 1944, [Kiev was liberated in November 1943]. My father was a member of the commission responsible for evaluation of damage. Our house was not ruined, but our apartment was occupied by engineer Bublik. He worked at the water supply unit and received a permit to move into our apartment from German authorities. In late April 1944 my mother, Alfred, my brothers and I arrived in Kiev. When we entered our apartment we saw as many pieces of furniture as one might find at a furniture store. Engineer Bublik took furniture from other people’s apartment. After the war our neighbors came to our apartment looking for their furniture. There was a special decision of court issued according to which Bublik had to either return furniture to its owners or compensate its value. We lived in the apartment of our neighbors that were still in evacuation for several more weeks. Back in 1937, at the 20th anniversary of the Soviet power, when my father worked at the Town Council and the Regional Executive Committee he was asked what award he wanted for his performance. My father said that he wanted a special writ of protection for his apartment. The Town Council issued a special decision that this apartment was given into my father’s ownership for a lifetime without any variations. When my father returned to Kiev he met with Mr. Gorbikov, Document Control Manager at the Town Council. He had saved the archives of the Town Council during the war. He had a house somewhere in the outskirts of Kiev. Before Germans came into town he buried the archive in a shed in his yard. After Kiev was liberated he returned the archive to the Town Council. This was a unique case since almost all towns had lost their archives during the war. Gorbik issued a copy of the writ of protection to my father. My father went to a militia department with this copy. He had two militiamen to accompany him to our apartment and Bublik was obliged to move out within a week’s time. He had a house in the outskirts of Kiev and left there. My parents, Lev, Boris and I moved back into our apartment.

After the War

When we returned from evacuation we noted a change in the attitude towards Jews. It was possible to hear ‘zhyd’ 23 in the streets that was never a case before the war. I also remember statements written in Russian and Ukrainian on the wall of some houses in the central part of the city ‘Whom did the Soviet power give education? Zhydy. Whom did the Soviet power give apartments? Whom did the Soviet power give this and that…’ This was the first time I bumped into evidence that Germans inspired antagonism of the local population against Jews. We knew from Soviet newspapers that they had exterminated Jews in their country. I got to know about Babi Yar in evacuation. Soviet newspapers didn’t mention that this was extermination of Jews, but that Germans were killing Soviet people. When we returned to Kiev eye witnesses told us the whole story. My father’s sister Dunia and her husband and Alfred’s sickly grandmother Julia perished in Babi Yar. Germans killed elderly people who were not able to walk as far as Babi Yar in their homes.

After the war my father was a member of the Town Collegium of Attorneys. He was responsible for helping Jews who were returning form evacuation to get back their apartments. This was not even a Jewish issue –this was the issue of protection of human rights. It was hard to have these issues resolved since apartments in the central part of the town were occupied by high-level officials. My father worked very hard. He hardly ever went to bed before 2 o’clock in the morning and got up at 8-8.30 in the morning. He did morning exercises and sponged himself down until he grew very old. My father reviewed all cases at home. He also worked part-time for the Town Council and executive committees and was too busy at work to review these applications in every detail. Besides, my father read special textbooks in law practices in the USSR and Ukraine. His colleagues and clients respected him a lot. Once we went to a party many years after my father died and one of the attendees said to me ‘ Your father taught so many generations of lawyers!’

My mother worked at a library after the war. One had to work to survive: employees received food coupons. My mother was not very fond of her work – she was a librarian. She was used to being a housewife and giving all her time to her husband and children. During and after the war we didn’t observe any Jewish traditions.

When at University, I was eager to do scientific work. In 1944 I went to the Institute of Physical Chemistry of the Academy of Sciences that had reevacuated from Ufa looking for a job. Deputy director told me that the only vacancy he could offer me was logistics lab assistant. Since I was Head of the Technical Control Department at the plant I had some experience and I agreed to take up this position until there was another vacancy associated with scientific research work. During our conversation Academician Brodski, a Jew, came into the office. Before the war he was a well-known specialist in heavy water area. Deputy director handed my application form to him.

Mr. Brodski looked through my documents and said ‘No, we can’t employ an A-student of the University as a lab assistant. Take another look: perhaps you will find another position'. I was employed as a lab assistant, but to the chemical department and in a year I was promoted to the position of junior scientific employee.

Lev had graduated from Radio Engineering Faculty of Kiev Industrial Institute before the war. After he returned to Kiev he became Director of Ukrainian Radio Trust. I remember the first radio programs in Ukrainian: about Soviet holidays – 1 May and October revolution [November, 7]. They were concerts and greeting of officials.

Boris continued his studies at the University in Kiev. He had studied at the Mechanic Mathematics faculty at Kiev University for two years before the war.

9 May 1945, Victory Day, was the happiest day. This was the holiday that didn’t need any administrative prearrangement. When we heard this announcement on the radio we ran to work. This was a warm day when chestnut trees had just begun to bloom. Here was a spontaneous parade. People went out to march hugging and kissing each other. This was the happiest day I could remember. It was more important than any other holiday and it united all people. This was the brightest day in my life.

Everything was in blossom. Alfred and I went for a walk. We came near the Opera Theater and there was a registry office nearby. Alfred said ‘Let’s drop in and register our marriage’. I said ‘I don’t have any documents with me’. He replied ‘I do’, He had my passport with him. We decided to get married when we were in Buzuluk, but since we all lived in a small room there we couldn’t even consider having another tenant. After we registered our marriage at the registry office we went to a ‘Mineral water’ small store across the street from the Opera Theater. There was a private bakery there. We scratched some money in our pockets to buy a bottle of Champaign and cakes. We went home and celebrated our wedding. Our parents were very happy for us.

After the wedding Alfred and I lived in my parents’ apartment in Kostyolnaya Street, we didn’t have a choice. Parents liked Alfred. In 1946 our son Georgi was born. After the war all employees were obliged to attend parades on Soviet holidays. This was horrible – they could even fire people if they missed a parade. I remember going to a parade with my one-year-old son in his winter coat just because I had to be there. My colleagues took turns to carry Georgi on their shoulders.

Lev married a Jewish woman in 1947, They had no wedding party. I can’t remember her name. They also lived with our family until they received apartment. In 1948 he received a room in the center of Kiev where he lived with his wife and daughter Zoya. Later their trust built a house in Pechersk in the center of Kiev. Lev received a two-room apartment. Lev divorced his first wife he never mentioned why. Zoya stay with her mother. After Lev married another woman, her name was Nina and she was Russian. They had a son: Sergey.

In 1947 Boris married Lisa, a Ukrainian woman, they didn’t have a wedding party either, we came to greet them with Champaign and cognac on the next day. Upon graduation from the university he became a postgraduate student. After finishing his postgraduate studies in 1952 he got an assignment to the Pedagogical Institute in Zhytomir. Boris, his wife Lisa and daughter Irina lived in Zhytomir for about 50 years.He defended his thesis, became Head of Mathematics department of Pedagogical Institute and became professor.

We began to listen to foreign radio shortly after we returned to Kiev. Lev installed an antenna on the balcony and we managed to listen to quite a few foreign stations. Actually, we could hear them at night the Soviets jammed foreign broadcasts. We listened to ‘Svoboda’ [Editor’s note: American radio station broadcasting in Russian from Germany] radio broadcasts in Russian. We heard about the events in the world and in our country that were not covered by our mass media. We all lived a dual life; we talked about achievements of our country at work and discussed the Soviet reality at home. In 1948 we were shocked by the death of Mikhoels 24, Head of the Jewish Antifascist Committee 25 during the war. He died in a car accident, but few realized his death was a part of Stalin’s plot we realized it then. After the war we all faced anti-Semitism (Jews had problems with getting employment or entering higher educational institutions, (Boris was lucky). Our family no longer believed that Stalin or other leaders were infallible.

Our family was very happy about creation of the state of Israel in 1948. I remember Golda Meyir 26 visiting Kiev, and how we admired her. There was coverage of her visit in newspapers. We didn’t feel like it was our country, Soviet Union was our Motherland and we were far from Jewish identity, but we did feel proud about our nation getting their own country.

Shortly afterward struggle against cosmopolitans 27 began. In 1950 I was thrown out of the Academy of Sciences under the aegis of reduction of staff. 15 other Jews were fired at the same time. When the list of employees to be fired was submitted to Alexandr Brodski, our director, at the Presidium of the Academy of Sciences he said ‘Please include my name into this list. If you fire my staff I won’t be able to continue to be director of the Institute’. He was not fired and managed to convince the administration to have all key personnel keep their job. Only younger employees were fired. Actually this was such an open campaign, you know, that no explanation was necessary. I stayed out of work for a year. Back in 1947 I fell ill with tuberculosis and when I lost my job I, obtained a certificate that I was an invalid to receive allowances and have justification for my jobless status. I was an invalid of category 2 and received a 30-ruble pension. In this year when I didn’t work I decided to write a dissertation. My father also fell under the category of cosmopolites and was fired from the attorney agency in 1949 or 1950. He didn’t go back to work. Alfred was the only breadwinner in our family. My father received a pension. Later in the early 1950s, he resumed his work at the attorney agency. He retired in 1959 since my mother was ill she had heart problems and father had to stay at home to take care of her.

In a year after I was fired from the Academy I received a phone call ‘Hallo, this is a scientific secretary of the Academy of Sciences. Could you come to see me at 11 am tomorrow?’ ‘Of course’. I went to his office with my passport and my labor record document. ‘We need to develop a unit to prevent emissions in mines. I would like to offer you a position of engineer for this work. Would you like to do this work?’ ‘I will, but please take a look at my documents’. He said winking at me ‘I don’t need to. I asked Alexandr Brodski to recommend a person to do this job and he said you are the best person he could think of’. So, this was Brodski that helped me to get a job. I was a free-lance employee of the Mining Institute.

In 1952 the ‘doctors’ plot’ began 28, but after the cosmopolitism campaign we didn’t believe mass media any longer. We didn’t believe Stalin was involved in these processes, we rather thought NKVD 29 played the main role. Stalin didn’t publicize his involvement in the processes like this. When Stalin died on 5 March 1953 I didn’t cry for him. We had a clear picture of what was going on. When I heard that he died I got scared a little: ‘What is going to happen now?’

In 1953 our son Georgi went to a Russian school in the center of Kiev. My son was doing well in all subjects, though he preferred exact sciences like Albert. He wasn’t raised Jewish, but always identified himself as Jew. He never faced anti-Semitism. He had friends of various nationalities and people treated him well.

I worked at the Mining Institute for four years until an order was issued to transfer it to Dnepropetrovsk. I went to work at the Road Transport Institute. Anti-Semitism mitigated, but I still got this job with the help of an acquaintance of mine. We had a great collective and management in the laboratory. I faced no anti-Semitism.

In 1960s Alfred and I got very fond of periodical publications. We subscribed to a number of magazines: ‘Novi Mir’ [popular monthly magazine], ‘Inostrannaya Literature’ [‘Foreign Literature’] from the time they began to be issued after the war. They published books by Soviet and foreign writers. There were shelves full of these magazines in the hallway of our apartment. But most important for us were Samizdat books 30 – the ones that were retyped. We read Solzhenitsyn 31 when it was retyped on thin cigarette tissue. We read books by forbidden authors when it was handed to one another. Our friends gave us copies and we gave them to our friends. Of course, this made a great impression on us since Solzhenitsyn was the first one to tell the truth about camps and innocent victims of the Stalin regime.

In January 1960 my mother died after being severely ill for a long time. She was 71. She was buried at the Jewish corner of a town cemetery, no traditions were observed. After my mother died I took the responsibility to keep family traditions. One of them was to have a family gathering on 9 January, on my father’s birthday. Previously my father’s close friends used to attend these gathering, but gradually it was just the family.

In 1960 I defended my thesis and became a Candidate of Sciences. I liked my work. We had a great team at work. We met at leisure time to go to a theater, Theater of Russian Drama that staged plays by Russian and Soviet classical writers and we also shared opinions about what we had read or seen. At weekends Alfred, Georgi and I went to a theater or concert.

In 1960s Khrushchev 32 promised that ‘In 1980 this generation of the Soviet people shall live under communism’, but we felt ironic about such things. To my mind planning economy was good for nothing. I took no interest in economic issues. I was busy at work, at home and with my son.

We liked traveling on vacations and went to a beach on the Dnieper River. Our laboratory was located in Darnitsa on the left bank of the Dnieper and I managed to go for a swim in the river before taking metro to commute to work.

Our son followed into his father’s steps. He graduated from the Faculty of Industrial Construction at the Construction Engineering Institute in Kiev. He is construction design engineer. Georgi has a Russian wife whose name is Svetlana. I had no objections to his marrying a Russian girl. In 1970 their daughter Elena was born. Georgi works a lot and has no free time. They do not observe any traditions: we didn’t and Svetlana also grew up in a non-religious family.

In 1976 my father died. We buried him near my mother’s grave at the Jewish corner of a town cemetery no traditions were observed. My father was involved in public activities consulting young lawyers at the Collegium of Attorneys and Town Executive Committee when he was a pensioner.

When perestroika began in 1985 books that we had read a long time before began to be published. Therefore, we were not surprised about what they published. We continued subscribing to newspapers and magazines. We listened to ‘Svoboda’ and radio of Israel – they were not jammed any longer.

I’ve been a pensioner for 16 years. I have great memories about my work at the Road Transport Institute. My former colleagues also remember me: they visit me on my birthday every year.

My older brother Leo was director of the Radio Trust of Ukraine before retirement. Leo died few year ago. His wife Nina, his daughter Zoya and son Sergei and their families live in Kiev. My younger brother Boris, his wife Lisa and their daughter Irina moved to America in1993. They live in Boston. I know that they are content with their life. They greet me on my birthday or New Year.

Alfred worked at the Scientific research Institute of Construction Structures before he turned 85, but even after he retired he continued providing consulting services to them. In 2002 Alfred passed away and it was a terrible blow for me. Shortly afterward I broke my leg and was confined to bed for a long time. There are no close people of mine left in Kiev. I am so happy that Georgi lives nearby. Besides my son, my daughter-in-law and my granddaughter, my old acquaintances and friends often visit me. Hesed takes care of us, old people, and I don’t feel lonely at all.

Glossary: