Evgenia Shapiro

Kiev

Ukraine

Interviewer: Elena Zaslsvskaya

Date of interview: November 2002

Evgenia Shapiro is a very sociable and attractive lady. She enjoys being interviewed. Her apartment is furnished with furniture from the 1960s. It is very clean and tidy. There is a very warm and friendly atmosphere in her apartment. One can feel that all family members love and care about one another. They have a very hospitable home.

All I know about my great-grandparents on my father's side is that they were born and died in the small town of Borisov, Belarus. In the 1990s I started research on the Jewish history of Borisov - it wasn't possible to do it earlier, as anything associated with the Jewish way of life was persecuted in the USSR. I managed to get some information. There were over 3,000 Jews in Borisov in the 1850s. Jews had lived in Borisov since the 16th century. They were selling bread and timber to Riga transporting it on the Zapadnaya Dvina River. There were seven synagogues in the town in the middle of the 19th century including Hasidic 1 synagogues. At the end of the 19th century there were tailors and weavers and traders of agricultural products in town. Jews owned sawmills and a match factory - the biggest enterprise in Borisov. There was a Jewish school, in which all subjects were taught in Russian. A Jewish hospital was opened at the beginning of the 20th century. There were private trade schools in town. The town was divided into two parts - a Jewish and a Belarus neighborhood, separated by the Berezina River.

My great-grandfather on my father's side, Juda Shapiro, was a hay-dealer in Borisov. He purchased hay from farmers traveling around the neighboring villages on his horse-driven cart. He wasn't wealthy. Prices for hay were low. Besides, it was a seasonal job. He died in Borisov before 1917 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. My great-grandparents were very religious and celebrated Jewish holidays. They went to the synagogue.

My grandfather on my father's side, Isaac Shapiro, was born in Borisov in 1876. He was deaf and dumb and had no education. He was a tailor. He was a very good tailor, but he didn't have many clients, as it was difficult to communicate with him. He made men's clothes. According to Jewish religious rules a man wasn't supposed to even look at a woman if they weren't acquainted, and so my grandfather never made women's clothes. He observed all religious traditions and celebrated Sabbath and Jewish holidays, although he wasn't fanatically religious. He didn't wear a hat or have a beard. He was a very kind and nice man - one could see it in his eyes. My grandfather had a drinking problem, though. My father often told me how his mother took him by the hand in the evening and how they went from tavern to tavern looking for my grandfather. By the time they found him he was usually dead drunk. They often found him on the roadside. He felt different from other people because he was deprived of their capability to hear and talk. Drinking helped him to forget about it for a short time.

Their family was poor. There were two rooms and a small hallway in their house. There were holes in the floor through which mice came into the house in winter. There were two beds, a cupboard and a big table in the rooms. All children slept near the stove. There were no books in the house.

My other great-grandfather, my paternal grandmother's father, Alter Dokshytskiy, was born in Borisov in the 1850s. He was a tinsmith. His family lived in the basement of a house. The dwelling was damp. There was no furniture in their dwelling. Children were born every year. Every afternoon their parents put a bowl of potatoes on the floor that served as a meal for the children. They didn't have many clothes - perhaps one dress or a pair of pants among the three of them. My great-grandparents had no education and didn't care about giving education to their children.

Their family was religious. They all spoke Yiddish. My great-grandfather went to the synagogue on Saturdays and on holidays and prayed at home on weekdays. They observed traditions and celebrated holidays as best as they could - they were so poor that they could hardly afford any special meals on holidays. They sometimes couldn't even afford candles.

My great-grandmother lost her sight when she grew older. In the last years of her life she either slept or sat on the floor of the hut. That's all I know about her. She lived a long and hard life. My great-grandparents died in Borisov before the revolution and were buried in the Jewish cemetery.

I only have some information about my grandmother, Nehama Shapiro [nee Dokshytskaya], and her brother Gdalia Dokshytskiy. Gdalia was born in Borisov in 1888. He was a copper worker. He moved to America in 1910.

My grandmother was born in Borisov in 1890. She could read and write a little. Her parents forced her into marriage in 1907 when she was 17. They were very poor and so they were keen to see their daughters married off at a young age. They made Nehama marry the first man that agreed to marry her. Her wedding party was small. It was a traditional Jewish wedding with a huppah. They borrowed a gown for the bride and a suit for the bridegroom from their neighbors. My grandfather was 14 years older than my grandmother. They had three children: my father Jacob, Lipa and Rebecca.

Lipa Shapiro was born in Borisov in the 1910s. He studied in cheder and finished Russian grammar school. In the late 1920s he moved to Leningrad where he worked and studied. I have no information about his occupation. He lived in a small room that he received from the office where he was working. He was recruited to the army in 1941 and got in German captivity the same year. The Germans executed him by tying him to two tanks that went in opposite directions. My father heard this story from somebody that witnessed this execution.

Rebecca Shapiro was born in Borisov in 1917. She finished Russian grammar school in Borisov. My father studied in Leningrad at the time. He received an apartment, and Rebecca and their parents moved in with him. She was impressed by the Soviet propaganda of equal possibilities for men and women and took to men's professions. She worked as a carpenter at a plant in Leningrad and then learned to drive vehicles. At the end of the 1930s she was a driver for the secretary of a district party committee in Leningrad. In 1938 she married Vladimir Rudnitskiy, a Jew. He was a pilot. In 1939 their older daughter, Ludmila, was born; in August 1941 Ella followed.

In October 1941 the blockade of Leningrad 2 began. Rebecca's husband was recruited to the front. Rebecca got a job with a crew of undertakers. She drove a car picking up corpses and received 50 grams of bread, which was more than the standard ration. When the 'Road of Life' 3 was opened, Rebecca and her daughters were moved to Siberia. After the war they all returned to Leningrad. Rebecca's husband also returned from the front. Rebecca was a shop assistant. Her parents survived in the blockade. Rebecca had another daughter, Galia, after the war. Rebecca's older daughter, Ludmila, finished a Russian school in Leningrad. She married Isaac Kozinets, a Jew, captain of the North Sea Navy. She lived in Severomorsk for several years. In the early 1970s she got divorced and returned to Leningrad with her two children, Julia and Michael. She worked as a guide in Leningrad. Now she's retired. Her daughter is an accountant, and her son is a construction engineer.

Rebecca's younger daughter, Elia, finished Russian secondary school and graduated from the Construction Engineering Institute in Leningrad. She worked as an engineer at design institutes in Leningrad. She's single.

Galia, the youngest daughter, was born in Leningrad in 1947. She finished Russian secondary school and married a sailor of the Navy. They moved to Severomorsk. Galia died when she gave birth to her baby-girl Gulia in 1970. Rebecca's other daughter, Ella, was raising her until the girl turned 2. At this time the father of the girl married a very nice and kind woman who became Gulia's new mother.

In the early 1970s Rebecca's husband died. After his death Rebecca spent three years lying on the sofa with her face turned to the wall. She didn't say a word in all this time and had hardly anything to eat. She died in 1977. They were both buried in the Jewish cemetery in Leningrad. Rebecca, her husband and their children weren't religious and didn't observe any Jewish traditions.

My father, Jacob Shapiro, was born in Borisov in 1908. When he turned 6 he went to cheder where he studied Hebrew, Torah and prayers. My father was successful with his studies and the council of Borisov that mainly consisted of Jews collected money for him to pay for his education at the Russian grammar school in Borisov. This wasn't common at all. Some of their non-Jewish neighbors solicited for my father's admission to the Russian grammar school. There were two or three other Jewish students besides my father. There was no negative attitude towards them. The only difference was that they were released from attending classes in Christian religion.

In 1917 the proletariat revolution took place. The post-revolutionary propaganda had great impact on my father. He was very enthusiastic about the ideas of equality and friendship of all nations and equal opportunities for poor people. My father was one of the first to become a Komsomol 4 member in 1919. He was authorized to organize the first pioneer units in Borisov. He completed his assignment successfully.

He began to work at the age of 14 to support his family. He was a court courier. He got 5 rubles and a food package (herring and bread). In 1920 he finished grammar school, and in 1922 he volunteered to the Red Army. He served in the courier unit until 1923. From 1923-1928 my father was an electrician, and in 1928 the Komsomol unit of Borisov gave him an assignment to study at Rabfak 5 at the Polytechnic Institute in Leningrad. He worked as an electrician during the day and attended evening classes. In 1931 he finished Rabfak and was mobilized to the army by the so- called Lenin's call. His authorities in the army sent him to study at the Military Communications College in Leningrad. He completed his studies in two years and got an assignment in the Far East where he was commander of a special radio unit. This unit was responsible for the receipt of information from Soviet intelligence officers, who were working in many countries around the world, and transmitting it to Moscow.

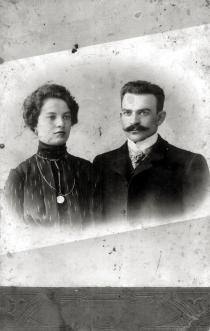

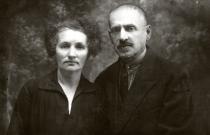

My father got married in 1932 when he was a military student. In the same year he became a member of the Communist Party. My father and mother had known each other for a long time. They were neighbors and used to play with other children near the Berezina River when they were teenagers. They went to pick mushrooms and berries in the forest and my father noted how pretty my mother was.

My great-grandfather on my mother's side, Gertz Gershenovich, was born in Borisov in the middle of the 1860s. He had a very good voice and was a cantor in a synagogue in Borisov. He was very religious. He wore a long jacket and had a beard and payes. He always observed traditions and celebrated Sabbath and holidays. He died in Borisov in 1917 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery.

My grandfather on my mother's side, Yuri Gershenovich, was born in Borisov in the early 1880s. He was an educated man, but I don't know where he studied. He owned a haberdashery store. He brought goods for his store from Warsaw and other Polish towns. His family resided in a nice two-storey house. The store was on the first floor and their apartment was on the second floor. There were three rooms, a kitchen and a hallway. They were nicely furnished. There was a table and a cupboard in the living room and comfortable beds in the bedroom. There were many religious and non- religious books in Yiddish in their home that my grandfather used to bring from Warsaw. They spoke Yiddish in the family, but all of them could understand and speak Belarus. My grandfather also spoke Polish and Hebrew. They kept a cow and had a housemaid to take care of the cow. She also cooked and looked after the children.

My grandmother on my mother's side, Fania Gershenovich, was born in Borisov in the 1880s. I have no information about her education, but I know that she could read and write. She was a cashier in the store. She didn't spend all her time there - she went upstairs to do things around the house from time to time. When a client came he would call her through a window. My grandfather spent most of his time on business trips. When he was at home he used to read the Torah and other books and spent time with the children. He went to the synagogue on Saturdays.

Their family wasn't fanatically religious. They didn't consider religion to be the most significant part of their life. They read many religious and fictional books and tried to give their children professional education rather than a religious one. They observed all Jewish traditions, but it was more a tribute to history than their conviction. They went to the synagogue on Saturdays and on holidays, as a tribute to traditions and a possibility to see their friends and acquaintances.

After the revolution of 1917 my grandfather worked as an accountant in an office in Borisov. My grandmother was a housewife. They stopped observing traditions after 1917. They were influenced by the Soviet propaganda speaking of the equality of all people and stating that religion was something people didn't need.

My grandparents perished in 1941 when the Germans exterminated the Jewish population of Borisov. All Jews were taken to the outskirts of the town and shot. Their bodies were thrown into a freshly dug pit.

My grandparents had six children: five daughters and a son. My mother's older sister, Tenia Gershenovich, was born in Borisov in 1906. She finished Russian grammar school in Borisov and graduated from the Institute of Economy in Moscow. During the war she was in evacuation in Zlatoust in the Ural. Her husband, David Mezo, was a rich timber merchant. He was a playboy and liked nice clothes, drinks and women. That's all I know about him. I only saw him twice when I was small. David later worked at the Mosgas gas supply agency in Moscow. Their daughter, Ella Zolotaryovskaya, lives in Israel. Tenia and David died in Moscow in the late 1970s and were buried in the Jewish cemetery. They never observed any Jewish traditions in their family.

My mother's sister, Faina Gershenovich, was born in Borisov in 1909. She finished grammar school in Borisov and an accountancy college in Moscow. She never got married. Her daughter Inna, born in 1936, graduated from the Institute of Chemical Industry in Moscow. During the war she was in evacuation in Cheliabinsk region, Zlatoust in the Ural. Inna is a pensioner now. Faina died in Moscow in 2001 at the age of 92. She was buried in the Jewish cemetery. She never observed any Jewish traditions.

My mother's third sister, Alexandra Litvin [nee Gershenovich], was born in Borisov in 1915. She finished Russian school in Borisov. During the war she was in evacuation in Zlatoust. She was a housewife. In 1973 she and her husband, Professor Fyodor Litvin, a Jew, moved to the US. Fyodor Litvin is a Doctor of Physics and still gets invitations to hold lectures in various countries all over the world. They live in Chicago and have two children. Their daughter is a doctor and their son is a programmer.

The next child, Ida Podolskaya [nee Gershenovich], was born in Borisov in 1917. She finished Russian school and graduated from the Faculty of Microbiology at Moscow University. During the war she evacuated to the Far East along with her laboratory. After the war she returned to Moscow. She was married to Daniel Podolskiy, a Jew. They have two sons. Her older son, Boris, is chief engineer for the reconstruction of Tsarskoye Selo and Pushkino [historical places in the outskirts of Leningrad]. Ida and her younger son, Mark, moved to New York in 1990. Mark graduated from the Institute of Shipbuilding in Moscow. He works for a big company in the US.

My mother's youngest sister, Sophia Ziskind [nee Gershenovich] was born in Borisov in 1919. She finished Russian secondary school in Borisov and graduated from the Optical-Mechanic Institute in Leningrad. During the war she was in evacuation in Zlatoust. She worked at optical institutes in Leningrad. She was married to David Ziskind, a Jew. She was his second wife. His first wife was shot by the Germans in Bobruisk, Belarus. David was a very nice and wise man. He died in Leningrad in the late 1970s. Sophia died in Leningrad in 1978 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. They never observed any Jewish traditions. Their daughter Irina and their son Michael live in the US.

My mother's brother, Samuel Gershenovich was born in Borisov in 1921. He finished Russian secondary school in Borisov. In 1937 he entered the Moscow Institute of Energy. In 1943 he went to the front where he was shell- shocked. He had to stay in hospital for some time and his hearing became worse as a result of the injury. He returned to Moscow and married a very imperious woman. Her name was Salia. She was Jewish and worked as a military surgeon. They moved to Minsk where she was working. He worked at the machine tool factory in Minsk. He was talented and invented many things. He died in Minsk in the 1980s and was buried in the Jewish cemetery. They never observed any Jewish traditions in the family.

My mother, Anna Shapiro [nee Gershenovich], was born in Borisov in 1910. She finished Russian grammar school in Borisov in 1923. At school she got inspired by revolutionary ideas and became a Komsomol member. Later she became a candidate for the party membership. My mother never observed any Jewish traditions. She spoke Russian, although her mother tongue was Yiddish.

In 1923 my mother went to work in a shop in Borisov. I don't know which one. She was also involved in Komsomol and party activities. She was responsible for the organization of the party meetings and conducting communist propaganda about equality and friendship of all people. She was also responsible for the distribution of the party literature. During this period she russified her last name to Gershanova. In 1931 she went to Leningrad to study at the School of Economics.

My parents got married in 1932. They had a civil ceremony at the registry office. They didn't have a wedding party. My father received an apartment when he was a student at the Communications College, and they lived in this apartment. I was born in Leningrad in 1933.

In 1934 my father got a job assignment in the Far East [35,000 km from Kiev]. We lived in a military town in the taiga, without a name, but a number. There was one apartment building for officers and their families, and barracks for soldiers. Life in the taiga was very hard. It was only possible to take a dirt road across the taiga to move to another location. These roads became impassable in rainy seasons. The forest was too thick to walk in it. There was also elfin wood in the taiga that made it impossible to walk. Summers in the taiga were short and cold: they only lasted one or two months, and the temperature was 20 degrees above zero maximum. There were swarms of mosquitoes and midges in the taiga. In winter the temperatures dropped to minus 40. Deep snow covered the land. Settlements were at great distances from one another and their population was few in number.

I was very thin, and my mother was very upset about it. She forced me to eat. I hated eggs, because my mother overfed me with them. She believed they were very good for me, but I had had too many and wanted a change. I wanted all chickens in the town to be dead. I had very thick hair and once my mother found a tick in it. Ticks were very dangerous carriers of infections, so my mother shaved my head.

When I was 5 I began to develop an ear for music and singing. We had a gramophone and records with popular songs. When my parents left me alone at home they turned on the gramophone for me to listen to records. Before they came back home I was fast asleep on the floor near the gramophone. They also left me with our neighbors when they needed to go to a neighboring village on business. My mother also looked after our neighbors' children when their parents were busy. I learned to read at 5. I read many children's books by Soviet writers. My father brought books from Khabarovsk where he went on trips.

The arrests of the 1930s 6 didn't affect our small habitation in the taiga. We heard about arrests of millions of people that were 'enemies of the people', but my parents didn't believe it. There were two or three people arrested in the Far East. One of them returned. His name was Petrovskiy. When he returned he was hiding at his friends' apartments, although he had been released from a camp. He had to follow residential restrictions and was supposed to stay at a specified location. He wasn't supposed to travel around, but he wanted to see his friends and came to see us illegally. My parents met him later in Kharkov, in 1957. He was a lawyer and awarded the title of 'Honored Lawyer'. He was grateful to my parents that they gave him shelter at a time when he needed it.

I went to school in a village a few kilometers from where we lived. In winter we were escorted to school by two soldiers, one of whom was plowing our way through the snow and one was watching us. I had a very good teacher, Raissa Mikhailovna. She was very nice and kind, but I took no interest in studying. I was bored at classes. I didn't like writing and received bad marks. My mother used to cry when she looked at my notebooks with 'bad' marks in them. I said to her, 'Why cry? It's only 'bad' and not 'very bad'.' The other children knew that I was a Jew, but there was no negative attitude. There weren't many Jews in the Far East, and there was no anti-Semitism.

In 1939 my sister Rina was born. In 1941, when the Great Patriotic War 7 began, we were evacuated to Evgaschino village in Siberia. We were evacuated from the Far East because the headquarters of the armed forces in the Far East were concerned about a possible attack by the Japanese army. My father served in the unit that was receiving reports from Richard Zorge 8, a legendary Soviet intelligence officer. They were all deciphered in Moscow. When they received information that the Japanese weren't planning any military actions they ordered us to return to the military unit. On our way back Rina got measles and this resulted in pneumonia. We couldn't get any medication, and Rina got meningitis. She was taken to hospital in Khabarovsk where she died in 1942.

Until July 1943 my father was a military commissar of the radio unit of the Far East front, and later he became head of this unit. He was the only Jewish head of the communications unit in the Red Army. My father had organizational skills and was a professional.

In 1942 the Eastern front headquarters transferred my father to the position of a commander of the communications battalion in Saratov. My mother and I followed him, but children weren't allowed to be with their parents during the war. I remember hiding in a bag. Other children were also transported in bags. When the train was inspected by the conductor's crew its passengers pretended they were having a snack on 'sacks full of potatoes'. I believe the head of the crew knew that there were children in those sacks, but he never made any comments in this regard.

In 1944 my father went to the front. We stayed in Saratov. My mother was a typist in a military unit. We lived in a small room in a barrack with two beds, a table and a couple of chairs. We didn't have any personal belongings - it was all army property. My mother received food packages, and I don't remember any lack of food.

I went to school in Saratov, but I don't have many memories about it. There was no anti-Semitism. I got along well with my teachers and schoolmates. Children went to the hospital after classes to help patients write letters to their families or fetch them water. I also went to the hospital. Nurses put me on a stool and told me to sing to patients. I sang popular romances by Izabella Yurieva and Claudia Shulzhenko. [Both of them were Russian pop singers and People's Artist of the USSR.] The patients enjoyed my singing and applauded me.

In 1944, when Kharkov was liberated, my father got an assignment to form a military unit in Kharkov. My mother and I followed him to Kharkov. I went to school there, but I don't remember anything about it because we only stayed there for a few months.

At the end of 1944 my father got an assignment in Kiev for half a year, and from there he was sent to be commander of the battalion in Ploiesti, Romania. My most vivid memory from our short stay in Kiev is the march of German captives along the streets of Kiev. They were dirty and shabby, these people. They could hardly walk and supported one another. A street- cleaning vehicle followed them, washing the streets.

When my father left for Romania my mother and I moved to Lvov. Families of the military weren't allowed to stay at military units located abroad. We lived in a room in a communal apartment in the center of town. It belonged to a military unit, and our neighbors were families of military. Within a few months all Polish inhabitants of the town were allowed to leave for Poland, and we received a three-bedroom apartment with luxurious furniture, all kinds of utensils and a grand piano from its former tenants. When we entered this apartment for the first time my mother slid down to the floor, overwhelmed by the luxury of it.

I remember one incident during our stay in Lvov. Lvov and Western Ukraine joined the USSR in 1939. The Ukrainian nationalists were against this union. The nationalists struggled against it on the side of the Germans during the war. On the day of the first elections of Soviet authorities my mother, who was taking part in all arrangements as a party activist, left home around 6 am and saw six corpses on the pavement near our house with signs on them, reading, 'That's what's going to happen to all that plan to vote'. This was a challenge to the Soviet power triggered by the Ukrainian nationalists. The elections took place nonetheless, and the majority of the population supported the Soviet power.

On 8th May 1945 we had guests. When, on the morning of 9th May, we heard the announcement on the radio about the capitulation of Germany, my mother and our guests began to hug one another and danced even though we were all wearing our nightgowns.

We stayed in Lvov until 1947. My mother worked as an economist. I went to school and got along well with my schoolmates. I had many friends. They were Ukrainian and Jewish children. I don't remember any anti-Semitism at the time.

In 1947 my father returned from Romania and got a job in Kharkov. My mother and I followed him to Kharkov. We lived in a small room at the military unit and later got a room at the Red Warrior hotel. After a year and a half my father received a three-bedroom apartment.

From the late 1940s to the early 1950s it was the period of the struggle against cosmopolitism 9 and the Doctors' Plot 10. Many of my parents' acquaintances were doctors of Jewish nationality. They were fired and suffered a lot under this campaign. My parents knew some doctors that were fired and deported from bigger towns to smaller ones. I didn't quite understand the situation. I believed everything the Soviet propaganda was saying. My parents didn't share their views with me. They were afraid that I might blurt something out and the whole family might suffer from consequences. My parents understood a lot more about Stalin and his regime, but this understanding didn't break their faith in communist ideals. My father was highly respected at his work although he was a Jew. My father always kept everything in order. He didn't drink or smoke. He was smart and well organized.

In 1948 my sister Margarita was born. I was very happy about it, as I always wanted a sister or a brother after Rina died. I finished secondary school in 1950 and decided to enter the Polytechnic Institute. At the time it was impossible for a Jew to enter a higher educational institution due to the state policy of anti-Semitism. It was also hard for Jews to find a job. I passed all exams successfully, but wasn't admitted. My father went to see the rector of the institute, but his secretary told him that the rector was busy and couldn't receive him. My father asked the commanding officer of his military unit to help. The commanding officer called the institute asking them why I wasn't admitted. It turned out that we had to give the secretary of the rector an expensive gift. She wanted an expensive woolen shawl. We found it and gave it to her. After this I was admitted to an evening department on the condition that I would be transferred to the daytime department if I studied at this department for a year with the highest grades. I did, but after a year I was admitted to the first year of the daytime department. So I had to do the first year again.

In the early 1950s my parents went to Borisov hoping to find the grave of my mother's parents. They couldn't find anything. There was a monument installed on the site of the mass shootings of Jews in Borisov.

In 1954 my father's father from Leningrad visited us in Kharkov. I couldn't communicate with him, but my father could using deaf-and-dumb language. We lived near the central park in Kharkov. My grandfather liked to sit on a bench in the park watching young women. Later he told my father about how many beautiful women there were in Kharkov and how happy he was to have seen them.

In the middle of the 1950s my grandfather was awarded the title of the 'Best fitter in Leningrad'. He was working at the garment factory and participated in a contest. His portrait was placed on the Board of Honor of the factory. My grandfather died in the late 1960s. My grandmother died some time before. They were both buried in the Jewish cemetery in Leningrad.

My future husband, Vladimir Vassiliev, was our neighbor and my classmate. He hated the Soviet power, and, arguing with my mother, he said, 'All those supporting the Soviet power should be hanged and its leaders killed'. When he visited us my mother closed all windows so that our neighbors couldn't hear us. My mother kept sighing saying that he was a bandit. He replied, 'Bandit or not, I will marry your Evgenia anyway'. My husband wasn't a Jew, but my parents had no objections to our marriage, because they didn't care about nationality.

My husband's father, George Vassiliev, was a Don Kazak. He was a professional military. My husband's mother was Ukrainian and had no education. She was a housewife and a nice and kind woman. My husband was born in Kharkov in 1933. After finishing secondary school he graduated from the Kharkov Construction Institute and became a civil construction engineer. He was a very intelligent and educated man. I loved him.

We got married in 1957. We had a civil ceremony at the registry office and then a big party. The following morning I moved to my husband's apartment in the same building. My parents and sister moved to Kiev where my father got a new job a few months after I got married. My husband's family didn't really like me. They never told me that they didn't like me because I was a Jew, but I could feel it. They were very correct, but very cold and reserved with me. They died in 1958-1959. My husband took good care of me.

In 1958 I graduated from the Kharkov Polytechnic Institute and became a mechanic engineer. I got a job with the Oxygen plant in Kharkov. I was head of shift at the plant that was located far from the city center. I had to cross an abandoned area on my way to work. I often worked nightshifts and once I was robbed: some bandits stole my watch. Another time they beat me. I quit my job at this plant. It took me nine months to get another job. Again I had problems due to my Jewishness. My husband went to the town party committee to explain the situation and complain about the fact that every time his wife filled in a questionnaire and the management found out that she was Jewish she was refused. They didn't believe him at the party committee and told him that it couldn't be true and there was nothing to worry about. Only when my mother came and asked her comrades to help me was I employed by Giproenergoprom, a design institute, at the technical information department. After seven years I went to work at the wiring factory where I was manager of the department of technical information until 1971.

In 1960 our daughter was born and named Tatiana after my mother's older sister Tenia. She wasn't raised Jewish. My husband wasn't a Jew and I wasn't raised Jewish either. In 1971 I divorced my husband and left for Kiev with my daughter to live with my parents. He died of cirrhosis in Kharkov in 1980.

In the 1970s many Jews were leaving the Soviet Union. My mother sympathized with them and used to say that she wouldn't mind moving either, but my father was strictly against it. One could see in his eyes that he believed all these people betrayed their motherland and communist ideals. Besides, he would have never been allowed to leave the country. He dealt with sensitive information at his work. He lectured on the coding of radiograms at the KGB intelligence department. When my mother's sister Alexandra moved to the US my father shouted that she was a traitor and he didn't even want to hear her name. But she wrote letters to us, and he read these letters with great interest. He also listened to Western radio, especially programs about Israel. During the Yom Kippur War 11 in 1973 my parents were stuck to their radio and very concerned about the situation.

We didn't observe any Jewish traditions. My parents were devoted communists and everything about religion seemed to be a vestige of the past to them, but my mother and father often talked in Yiddish.

My parents arranged parties at home on Soviet holidays. Most of their friends were Jews. They discussed quite a few Jewish issues like the departure of Jews from the Soviet Union, anti-Semitism and the situation in Israel. There were no religious Jews among their friends. They were all Soviet people and many of them were members of the Communist Party.

I was an engineer at a construction company in Kiev. I was responsible for the selection and preparation of sites for housing construction. For ten years I went to work in Nefteyugansk [3,000 km from Kiev]. My daughter stayed with my parents in Kiev. Engineers and workers had an opportunity to get a job in the North where salaries and wages were higher due to the severe climate and work conditions. It was also difficult to cope with the hardships of life there because of the polar night that lasts half a year and when there is no sun. People signed contracts for several years to make a significant amount of money. There were oil deposit developments and construction sites in the North. So, work in the North was better paid, and I wanted to earn a little before my retirement. I had the time of my life in the North. I worked with nice people. We were a great team. I lived in a room with a fridge and a TV. We celebrated holidays and birthdays together. We flew a helicopter to pick mushrooms. We put on our rubber boots and anti- mosquito nets and went to pick red bilberries. I enjoyed it very much there. I returned to Kiev in 1984 when my daughter decided to get married. I still keep in touch with my former colleagues from Nefteyugansk.

My mother became a housewife after my sister was born in 1948. My mother was a very sociable and easy-going person. She got along well with people. In the late 1970s she had a stroke and couldn't walk anymore. The janitor of the house (he wasn't a Jew) made a bench for her in the yard and handrails at the entrance so that she could come out to sit in the yard. All our neighbors kept her company whenever they could. She died in 1986 and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev.

My father retired from the army in 1959. He got a job as a senior engineer at the equipment department in Montazhspetsstroy. This company was involved in the preparation of construction sites. My father worked there until 1994 when he turned 86. My father lived with me and my daughter.

In the early 1990s, when Jewish life in Ukraine began to revive, my father used to watch TV programs about Israel. He said that he might have done well if he had moved to Israel. We discussed departure but my father kept saying that he couldn't leave his wife's grave. We subscribed to Jewish newspapers and went to Jewish concerts. My father said that he would have attended the Jewish community, but that he was too old for any activities of this kind. He was 90. In his last days he only spoke Yiddish. We couldn't understand what he wanted, but he didn't say a single word in Russian during the last week of his life. A few days before he died he began to sing prayers. My father died at the beginning of 2001. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Kiev.

My sister, Margarita, finished secondary school in Kiev and graduated from the Construction Institute in Rovno. She worked as construction engineer in design institutes in Kiev for many years. Her husband, Andrei Gurin, isn't a Jew. They have two sons: Alexei and Anton. They all moved to Germany in 1997. They live in Berlin. My sister is a pensioner and her older son works at a tram depot. Her younger son studies. They have everything they need and are happy about it. My sister misses Kiev. She often calls me and sometimes comes to see me.

My daughter Tatiana finished secondary school in Kiev and graduated from the Construction Institute in Kiev. She is a construction engineer and works at a design institute. In 1984 she married Evgeniy Yakushko. He isn't a Jew. They have two children: Yuri, born in 1985, and Anna, born in 1988. Anna is finishing school now and Yuri studies at the Faculty of Biology at Kiev State University. Tatiana's husband died of cancer in 2001. It was a tragedy for all of us. He was such a wonderful man.

I am very pleased that Jewish life has revived in Ukraine. I don't take part in it, as I'm very busy at home taking care of the housework and looking after my grandchildren. But I always enjoy going to a concert of Jewish music or some other performances. I receive food packages from Hesed.

We won't move to Israel. My daughter wouldn't be able to find a decent job there. Besides, she isn't very good at languages and wouldn't be able to learn Hebrew. My grandchildren also want to live and study in their hometown.

Glossary